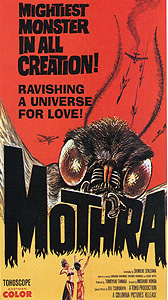

Mothra / Mosura / Daikaiju Masura (1961/1962) **

Mothra / Mosura / Daikaiju Masura (1961/1962) **

The first wave of Japanese monster movies owed a great deal to the American films that inspired them. Godzilla: King of the Monsters differed from its models mainly in the scale on which it operated and in its unmistakably overt allegory. Rodan was in some ways even more American-seeming, at least up until its ending— no American filmmaker would have been so quick to impart recognizable human emotions to a 16,000-ton pterosaur. And Half-Human (to the extent that the character of the original can be determined at all from the severely mauled English-language re-edit) had little to offer that could not be found in a contemporary American or British bigfoot/yeti movie. But already by 1957, the makers of Japanese sci-fi films were starting to find their own distinctive voice. One needn’t watch The Mysterians for too long before it becomes clear that it is a movie of a totally different breed from War of the Worlds or Earth vs. the Flying Saucers, no matter how similar the subject matter may seem on the surface. The release of Mothra/ Mosura/Daikaiju Masura arguably marked the end of this period of growth and self-discovery. Sequel mania would set in at Toho the very next year (and at the rival Daiei studio as soon as that company returned to making sci-fi and fantasy movies in 1965), leading to an ever more rigid codification of the kaiju eiga formula and an eventually exclusive concentration of creative energy in the genre on entries in the Godzilla (or Gamera) series. Mothra was Toho’s last major monster movie that was not a sequel to something else, but it is probably also the first Toho monster movie about which it can honestly be said that no Westerner could possibly have made it. It is unfortunate, then, that its creators tried so hard to force it into a conventional 50’s monster framework; its most distinctively Japanese story elements are constrained and stunted by the demands of the old formula, yet simultaneously take time and energy away from the very things that made that formula viable.

Mothra begins with that ancient standby of Japanese monster flicks, the ship in distress. The freighter Genjin Maru is being hammered by a typhoon when it blunders onto a coral reef and breaks its back. Fortunately for at least some of the sailors, however, one does not typically encounter coral reefs out in the open ocean, and sure enough, a few men are able to escape from the disintegrating ship and find safety on tiny, remote Biru island. (So does this mean Toho changed the name of the island for subsequent films, or does “biru” mean “infant” in Japanese?) The only problem with this is that Biru lies smack in the middle of a stretch of sea where the uncouth and arrogant nation of Rolisica (the Japanese cinema industry wouldn’t get up the nerve to cast aspersions on the US directly for another couple of years) had been in the habit of testing its nuclear weapons. But oddly enough, none of the shipwrecked sailors exhibits any sign of radiation sickness when they are picked up by a rescue helicopter several days later. One of the castaways attributes their health to the juice that the natives of Biru gave them to drink.

All this is big goddamned news back home. First of all, it involves the survival of a lucky few in the face of disaster. Second, there’s the matter of juice from a hitherto unknown plant having the power to protect its drinkers from dosages of radiation that should surely kill them. Finally, there are the sailors’ references to the “natives” of Biru— the island is supposed to be totally uninhabited, so anthropologists and adventurers start crawling out of the woodwork at the first mention of natives. With all those angles to work, it should come as no surprise that every newspaper in Japan descends on the sailors, their rescuers, and the planned scientific expedition to Biru like flies on shit. Most of the journalists we needn’t concern ourselves about. The only ones who matter for the next 90-odd minutes are a big, fat reporter named Senchiro “Bulldog” Fukuda (The Last War’s Frankie Sakai) and his photographer associate, Michi Hanamura (Kyoko Kagana). Their rather sensationalist newspaper is desperate for a scoop, so much so that the editor is even willing to have Fukuda sneak aboard the ship on which the expedition to Biru is to sail. (Michi can’t come, because a woman with a camera would attract way too much attention.)

The head scientist on the trip to Biru is named Haradawa (shortened to just “Harada” in the American version— either way, he’s played by Ken Uehara of Gorath and Atragon); he was the white coat to whom the sailors were entrusted after their rescue. But strangely enough, neither he nor anthropologist Dr. Chujo Nakazo (Hiroshi Koizumi, from Godzilla vs. the Thing and Dagora the Space Monster) has any real authority over the mission. Principal financing from the venture is coming from a Rolisican businessman called Clark Nelson (Jerry Ito, from Message from Space and The Manster), and because it’s his money, he feels entitled to call the shots. Nelson is the guy Fukuda really wants to get close to, as it is immediately obvious that the Rolisican has more secrets than a whole roomful of KGB agents. Fukuda has more persistence than brains, however, and he gets himself found out before the ship even reaches Biru. Only the intervention of Dr. Nakazo, who doesn’t like Nelson any more than the reporter does, saves Fukuda from spending the rest of the trip locked up below decks.

In fact, Fukuda even gets to go along when the team lands on the island, and thus he is party to an amazing discovery made by Nakazo. The scientist gets separated from the other men, wanders into a cave, and discovers strange, prehistoric-looking plants— this must be where the islanders get their anti-radiation juice from! But the plants turn out to be carnivorous, and one of them attacks Nakazo. Each team-member’s radiation suit is equipped with an alarm siren, though, so Nakazo doesn’t have to struggle alone for long. However, the rest of the explorers aren’t the only people who respond to Chujo’s siren— the shrill sound also draws a pair of pretty young women about a foot high! We never do learn the girls’ names (I can tell you they’re played by Emi and Yumi Ito, who had been pop singers of some note as the Peanuts during the late 1950’s) or what exactly it is that they find so fascinating about an electronic siren, but the moment he finds out about them (despite the efforts of just about everyone on the ship to keep their presence a secret), Nelson has an attack of the Carl Denhams. He and a couple of armed thugs go back to the island the moment all the scientists and technicians are in their bunks, and kidnap the tiny twins, shooting their way through the full-sized natives who try to stop the abduction.

Nelson’s idea, of course, is to make a fat wad of cash by exhibiting the miniature islanders at his nightclub in Tokyo. (What? I thought all crooked venture capitalists operated nightclubs on the side...) Their act consists of them being lowered onto the stage in a little gilded coach and singing folk songs from their island. And interestingly enough, all the songs they know (the lyrics aren’t dubbed into English in the Western version, thank the kami) seem to be about something called “Mosura.” Why is this interesting, you ask? Well while he was on the island, Nakazo had time to copy down some inscriptions, and his efforts to translate them have hit a stumbling block in the form of a recurrent character the meaning of which he cannot determine, but which he has somehow figured out is supposed to be read “Mothra.” Say it with a thick Japanese accent, and what do you get?

Apparently you get a remarkable linguistic coincidence, for just then, we return to the island, where a gaggle of Japanese extras in hilariously bad blackface are busy bringing a humongous caterpillar to life by means of an overly lengthy song-and-dance number. Who’d have thought “moth” was one of those words of such universal importance that it would retain its original form throughout the diffusion of language across the globe? This caterpillar makes straight for the ocean, and starts swimming for Tokyo.

Meanwhile, back in Japan, Fukuda, Michi, Nakazo, and Nakazo’s 12-year-old brother, Shiro (Akihiko Tayama— and folks, I believe we’ve finally found the original Kenny), somehow convince Nelson to let them see the twins. To the audience’s good fortune, the girls turn out to be telepaths, and are therefore able to get around the language barrier and provide some real exposition at last. This Mothra is apparently the patron god of Biru island, the girls are Mothra’s priestesses, and the giant bug is homing in on them telepathically to bring them back where they belong. And if Japan should happen to be in the way when that happens, then that’s just too fucking bad for Japan. Nelson, of course, pooh-poohs the story, but he changes his tune when that 50-meter caterpillar shows up in Tokyo and starts wrecking the place. What he doesn’t change is his stance on relinquishing the twin priestesses. Instead, he goes crying to the Rolisican embassy, and rather implausibly persuades his home government to back Japan militarily against the monster. Then he sneaks out of the country with the tiny girls in his suitcase. That may work to get a big-ass caterpillar off his back, but after Mothra spins a cocoon on what’s left of Tokyo Tower and emerges as an imago despite the best efforts of the Japanese and Rolisican militaries to destroy it while pupating... well that’s another story altogether. Mothra takes wing, leaves Japan for Rolisica, and starts leveling Newkirk City, where Nelson is hiding out. It’s a good thing for Rolisica that Nakazo and his friends follow the giant insect to Newkirk with a viable plan for making peace with an angry god...

Now it sounds cool when I describe it, doesn’t it? We’ve got a slick inversion of King Kong, a somewhat more skillful reprise of the city-smashing scenes from Rodan, and a whole lot of stuff that no one in Hollywood would ever have thought of. Not only that, Mothra features the largest-scale miniatures in the entire Toho canon, making for the most beautifully detailed destruction of Tokyo yet filmed. But somehow the parts don’t quite fit together right. The Twin Fairies— probably the most attention-getting feature of the whole film— never have much to do. In contrast to their later appearances in Godzilla vs. the Thing and Ghidrah, the Three-Headed Monster, their role here is entirely passive, and they end up being rather uninteresting. The idea of a basically good monster raining destruction on the innocent because of the actions of a few corrupt men is another brilliant twist on the formula that is never given enough room to operate. Mothra itself just isn’t a big enough presence in the movie to allow for a serious exploration of what it represents, but at the same time, the knowledge that we’re supposed to be rooting for the monster deprives the rampage scenes of most of their impact. The latter effect is only intensified by the obvious absence of people from the city sets Mothra destroys, an unfortunate side effect of the larger scale on which they were constructed. Another major problem has to do with the way the movie’s human characters were handled. Screenwriter Shinichi Sekizawa seems to have been unable to settle on any one person to be the main protagonist, but he also failed to create anything that might meaningfully be called an ensemble. Instead, the dramatic emphasis shifts with little apparent regard for the flow of the story between Fukuda, Nakazo, and even Shiro. With this wandering emphasis on the one hand, and the equally indecisive vacillating between 50’s formula elements and radical departures from them on the other, it’s hardly surprising that Ishiro Honda’s direction seems profoundly confused and, frankly, directionless. Nevertheless, Mothra was a hit, both in Japan and in the United States, and after King Kong vs. Godzilla showed just how big a moneymaker a kaiju sequel could be (the earlier Gigantis the Fire Monster/Godzilla Raids Again hadn’t done nearly as well), it was inevitable that the giant lepidopterid would be coming back for more. Most of Mothra’s subsequent appearances would be more than a little on the lame side, but the monster’s first return engagement— Godzilla vs. the Thing— was everything the original Mothra should have been, but wasn’t.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact