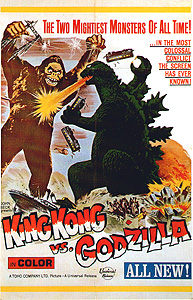

King Kong vs. Godzilla/Kingu Kongu tai Gojira (1962/1963) **

King Kong vs. Godzilla/Kingu Kongu tai Gojira (1962/1963) **

The origin of King Kong vs. Godzilla is as convoluted as any in the annals of film, as is perhaps only to be expected of a Japanese sequel to an American movie made nearly 30 years previously. The story spans decades, continents, and cultures, tying itself into all manner of incestuous little knots along the way, and leaving a trail of forgotten, lost, and stillborn movies in its wake. The most surprising wrinkle of all has only recently come to light, however: King Kong vs. Godzilla was apparently not the first attempt to make a Japanese King Kong movie! In 1938 some Japanese studio (I have not been able to determine which) released a film entitled Edo ni Arawareta Kingu Kongu— “King Kong Appears in Edo.” Edo ni Arawareta Kingu Kongu probably never played outside of its home country, and has been lost for decades. Some cast and crew information survives, along with a few hints that the movie might have prefigured the much later Pulgasari by injecting a giant man-in-a-suit monster into what would otherwise have been a fairly standard historical drama, but that’s about all that can be determined at this late remove. There is, however, at least one sense in which Edo ni Arawareta Kingu Kongu is indisputably within the direct lineage of Toho’s later Kong movies— Fuminori Ohashi, who created the 1938 ape suit, was part of the team that built the original Godzilla costume in 1954.

Meanwhile, back in the United States, King Kong special effects maestro Willis O’Brien was planning a third Kong film. The idea was to pit the giant ape against a mad scientist and his custom-built megafaunum, and while the project went by several titles over the course of its development, the name under which it was eventually sold was King Kong vs. Prometheus, a rather illiterate reference to the subtitle of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus. Unfortunately for O’Brien, none of the majors were interested, and he ended up selling the story to John Beck, an independent producer who had recently split from Universal. The reasons for the studios’ reluctance are not difficult to fathom. For one thing, it was pretty obvious in 1960 that giant monsters were on the way out in Hollywood, and that it would be difficult to turn a profit on the film if it were made according to O’Brien’s usual standards. Beyond that, there would inevitably be a set of expensive legal hoops to jump through. RKO, which had released the two Kong films back in the 30’s, was no longer in business as an active production company, but it still officially existed, following what might be called an undead business model. Rather than making new movies, RKO subsisted by keeping its old ones in circulation, and in the case of King Kong, by licensing spinoff rights (but not, significantly, by licensing a flat-out remake— no less a studio than Hammer Film Productions got rebuffed when they tried to buy the remake rights to King Kong). As you might imagine, those Kong-related licenses didn’t come cheap, and the big ape was effectively priced out of the market in Hollywood.

Japan, however, was a different story. The kaiju craze showed no sign of abating as the 50’s wore on into the 60’s; in fact, it would be fair to say that it was just hitting its stride. When Beck offered King Kong vs. Prometheus to Toho in exchange for a commitment to Universal as the US distributor of the finished film, the studio heads jumped at the chance to have a Kong of their own, even though RKO wanted an eye-popping $200,000 for the sequel rights. Once the script was in Toho’s hands, however, it underwent an odd sort of reproduction by fission. The Frankensteinian elements were split off, and followed their own five-year path through Development Hell before finally emerging as Frankenstein Conquers the World. The King Kong aspect, meanwhile, was retooled into what amounted to a gala re-launch for Toho’s long-dormant original monster franchise.

Godzilla: King of the Monsters had, of course, been a huge hit, but Gigantis the Fire Monster, the quickie sequel rushed into the theaters in 1955, fared poorly at the box office, and Godzilla fell silent for years while Rodan, Varan, Mothra, Magma, and Mogera ran rampant. That 200 grand Toho forked over to RKO changed things, however. With that kind of overhead sunk into nothing but a goddamned character license, the only sensible thing to do was to go all-out: color, widescreen, stereo sound, the works. And what better way to stack the deck in favor of what would unavoidably be a hazardously expensive movie than to make King Kong’s opponent the only other monster in the world with enough icon-cred to rival his own? Godzilla would get a second chance at franchise-hood, and this time the venture would be so successful that the sequels wouldn’t stop coming for thirteen years.

As is so often the case in a monster movie, we begin with a couple of weird natural phenomena. The more obviously worthy of concern has to do with an aberrant temperature increase in one of the cold-water currents that flows down toward Japan from the Bering Sea. Heaven alone knows what sort of ecological breakdown that could foretell, and the Proper Authorities (the American version makes it the United Nations, but my suspicion is that it was originally supposed to be the US Navy) have sent a nuclear submarine to the source of the current to investigate. Meanwhile, and more prosaically, operatives of the Pacific Pharmaceutical Corporation have learned of a hitherto unknown berry growing on the hitherto unexplored Faro Island, which is regarded by the natives to have strong but non-addictive narcotic properties. PPC boss Mr. Tako (prolific comedic actor Ichiro Arishima, whose other forays into our usual territory include The Vampire Moth and The Lost World of Sinbad) understandably believes that this discovery could be worth a fortune to the company, and so he dispatches three of his best men— Osamu Sakurai (Tadao Takashima, from Son of Godzilla and Across the Universe), Kuzuo Fujita (Kenji Sahara, of Godzilla vs. the Thing and War of the Gargantuas), and Kinsaburo Furue (Yu Fujiki, from Atragon and Yog: Monster from Space)— to Faro to bring back sufficient quantities of the berries for research. Tako also wants his agents in the field to look into reports that the Faro Islanders worship some sort of titanic monster. He seems to think that if there really is such a creature, it would make the perfect mascot for the new berry-derived drugs in Pacific Pharmaceuticals’ advertising campaign.

The submarine gets where it’s going before Sakurai, Fujita, and Furue even ship out for Faro. It would appear that the source of the excess heat is a rapidly shrinking iceberg, the interior of which is glowing with erratic flashes of alarming blue light. The dumb-asses manning the sub manage to get their vessel hung up on the underside of the glowing berg (but perhaps they deserve at least a little slack here, since they probably spend most of their time in our universe, where ice floats on liquid water, and would thus not have expected the hail of falling chunks that batters them into the crevice where they become trapped), and so they’re just as fucked as they can be when Godzilla claws his way out of the much-weakened ice. I’d have thought it would take significantly less than seven years for a fire-breathing monster to free himself from the bottom of a pile of ice, but since we’re looking at one of the few tiny nods in the direction of inter-episode continuity to be seen anywhere in the Showa Godzilla series, I should probably just shut the fuck up about it and be thankful for small blessings. Godzilla makes a beeline for Japan and wrecks the shit out of a city or two before wading out into the ocean for a nice, long nap.

As for the Faro Island excursion— well, you’ve all seen King Kong, right? Well, take the Skull Island portion of King Kong, cast Abbott and Costello as Carl Denham and Jack Driscoll, and then make everybody Japanese, and you’ve got approximately the idea. There are a couple of notable differences, though. For one thing, there’s no Fay Wray analogue here (King Kong won’t be meeting Sakurai’s sister, Fumiko [Mie Hama, who would cross paths with the giant ape again in King Kong Escapes], until he reaches Tokyo), and the natives are halfway plausible as stone-age primitives from the South Pacific. Also, there are no dinosaurs running around in the island’s interior, although the coastal village where the PPC guys stay is subject to nighttime attacks by a giant octopus. The Great Wall is more of a Great Picket Fence, and therefore needs no door to allow for the occasional communication between the beach and the jungle. And finally, there’s the new King Kong. This being a Toho movie, Kong is a man in a gorilla suit. Contrary to what you may have heard, this is not because special effects director Eiji Tsuburaya couldn’t master the intricacies of stop motion (in fact, there will be a jarringly obvious stop-motion moment during the second clash between Kong and Godzilla), but rather because Tsuburaya already had a highly developed technique of his own, which was vastly cheaper and less labor intensive than O’Brien’s— not a trivial consideration when a perfectly respectable movie could have been produced on just the licensing fee for the Kong character! Unfortunately, this particular gorilla suit is not one of Tsuburaya’s more impressive creations. In fact, as my brother once put it, it looks like it was stitched together out of carpet samples, set on fire, and then put out by beating it with a heavy board. Its wretchedness is all the more striking in comparison to the Godzilla suit for this outing, which gets my vote for the best of the whole Showa era. Toho must have known what a disgrace the Kong costume was, too, for it appears in none of the Japanese advertising art for King Kong vs. Godzilla— stills of the original O’Brien Kong were matted into images from the new movie instead. In any case, the climax of the island subplot comes when Kong marches down from his mountain to save the village from an octopus attack. The cephalopod defeated, Kong then proceeds to guzzle down all of the islanders’ stock of berry juice, lapsing into a deep stupor, and giving Sakurai and company their chance to rig him up for transport to Japan.

What happens next is the most logical thing ever to occur in a Japanese monster movie— so logical, in fact, as to be really quite shocking. The Pacific Pharmaceuticals ship is stopped just outside of Japanese waters by the military, and its crew placed under strict orders to turn around and take Kong back where he came from. There’s already one giant monster on the loose, after all, and Tako’s belief that he can control Kong is obviously nothing but wishful thinking. Alas, Kong picks that moment to wake up. Freeing himself from the giant log-raft on which he was being towed, the huge ape escapes from his would-be owners and swims— you’ve got it— directly for Japan. Apparently he and Godzilla are “natural enemies,” or some such foolishness, and neither one can abide the presence of the other within comfortable traveling distance. Some natural enmities are apparently best left un-acted-upon, however, for the monsters’ first meeting ends with Kong slinking off like a great big pussy after a couple of near misses from Godzilla’s atomic breath. One assumes that it is in order to salve his manly (okay, apely) pride after such an ignominious rout that Kong immediately attacks Tokyo in a Reader’s Digest Condensed Rampages version of the classic New York sortie. Nevertheless, it’s obvious enough that King Kong and Godzilla each represent Japan’s best hope for getting rid of the other, and since the military forces under General Shinzo (Jun Tazaki, from Gorath and Destroy All Monsters) have had no luck whatsoever in dealing with either monster, all attention turns to finding a way to encourage a rematch.

Successful though it was (and if we adjust for inflation, it’s still the highest-grossing of all Toho’s Godzilla movies), King Kong vs. Godzilla has to be reckoned a major disappointment. It just seems like a showdown between two of the world’s most iconic monsters ought to have slightly more oomph to it than this rather wobbly spectacle of Godzilla kicking debris at an ape suit that even Crash Corrigan would have turned up his nose at. However, that leaves open the question of how to apportion the film’s failings between its creators and US distributors Universal International, and that question is hard to answer on the basis of the American version alone. It is immediately obvious that few Japanese monster movies have been so drastically altered for importation to the States, and while some of the changes Universal made are understandable, the majority are simply baffling. While it was commonplace for American companies to edit a few home-grown actors into foreign-made genre movies, the scenes in King Kong vs. Godzilla with Michael Keith (The Worm Eaters), Harry Holcombe (Empire of the Ants and Foxy Brown), Byron Morrow (Cyborg 2087 and Black Zoo), and James Yagi (The Revenge of Doctor X), are so thunderously dull and so obviously purposeless that it’s hard to see how their inclusion could have helped sell the movie to US audiences. Similarly difficult to grasp is the reasoning behind jettisoning Akira Ifukube’s score in favor of much more generic-sounding music recycled from Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man and Creature from the Black Lagoon, or for editing in the earthquake and space-station footage from The Mysterians. With so much other tinkering going on, it would be easy enough to believe the persistent rumor that Universal re-edited the movie’s ending to make King Kong rather than Godzilla the victor in the final clash— although in fact, as other reviewers before me have observed, the outcome of the fighting was just about the only thing that didn’t change between the Japanese version and the American.

I did, however, say that some of the alterations make sense; as it happens, the most understandable change of all is the one that effectively turns King Kong vs. Godzilla into a totally different movie from Kingu Kongu tai Gojira. This is not remotely apparent from the version we saw in the English-speaking world, but King Kong vs. Godzilla was not originally intended to be a conventional monster movie at all. Rather, reliable modern reports have it that the Japanese version might best be thought of as a salaryman comedy that uses a pair of giant monsters as its central plot device. The salaryman comedy is a uniquely Japanese form of light satire that pokes fun at the foibles of a uniquely Japanese form of postwar middle-class life. The whole plotline leading to King Kong’s arrival in Japan— the well-meaning but slightly hapless protagonists, the bizarre and obviously unreasonable assignment, the boss with an unshakable fixation upon a patently delusional business strategy— is a textbook salaryman premise, and the casting of Ichiro Arishima (who was a mainstay of salaryman comedies, and would remain so until the end of the decade) as Mr. Tako would have immediately cued Japanese audiences to expect such antics, monster or no monster. Naturally, the whole basis for much of the film’s original humor would not have survived the trip across the Pacific, and Universal may therefore be forgiven for recasting the Pacific Pharmaceuticals material as more traditional Hollywood comic relief. The problem is that in doing so, Universal also demoted what had been the core of the movie to a mere subplot, and the more mainstream monster action that remains lacks the substance to carry the movie on its own. The result is that the US King Kong vs. Godzilla feels disjointed and fragmented, almost as if it were never quite completed.

Then again, one might legitimately ask whether a kaiju salaryman comedy was something the world really needed, and if the comedy portions of King Kong vs. Godzilla retain any of their original flavor, then my instinct would be to answer that question in the negative. Ishiro Honda, too, was reputedly not happy with the directives from upstairs to help declaw the genre he had done so much to create, but it must be remembered that comedies like Arishima’s usual stock in trade were Toho’s main source of income during the 1960’s. Partly that was because they didn’t cost anything to make, but mostly it was because they sold tickets hand over fist in a way that old-fashioned monster movies did not by 1962. Looked at from that perspective, King Kong vs. Godzilla becomes an experimental answer to a problem that would ultimately be solved in the long term by making Japanese sci-fi and fantasy movies simultaneously cheaper to produce and more alluringly bizarre. The box-office returns would argue that the experiment was a successful one, but the lack of subsequent kaiju eiga/salaryman hybrids suggests that Toho and their competitors found it difficult to reproduce.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact