Pulgasari (1985/2001) **Ĺ

Pulgasari (1985/2001) **Ĺ

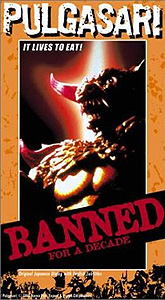

Not too long ago, we took our first look at a South Korean monster movie. Now let's cross the 38th Parallel, and see what the North Koreans have done in the same field. If you should run across Pulgasari and English is your first language, then chances are what youíve picked up is AD Visionís home video edition from a couple of years ago. In that case, itís a safe bet that the first thing you noticed was the tagline, ďBANNED for a DECADE!Ē emblazoned across the front of the box. Now thatís quite a come-onó banned where? And why would anybody want to ban a kaiju movie in the first place? Well have a seat, Ďcause itís time for a little story. Actually, reliable details have proven maddeningly difficult to track down. For example, Iím not at all certain that Pulgasari ever really was banned, per se. There is some indication that it was never shown in its country of origin, but considering how tight-lipped authoritarian dictators tend to be about their real reasons for doing things, that doesnít necessarily amount to an outright ban. And in light of the effort that Kim Jong Ilís regime invested in shopping the movie around to distribution companies elsewhere in Asia in the late 1990ís, one can only conclude that Pyongyang must have gotten over whatever it was about Pulgasari that bothered it back in 1985. But to begin at the beginning...

In the early 1970ís, Shin Sang-ok was one of South Koreaís most respected filmmakersó meaning, you understand, that he was pretty much unknown outside of East Asia except among a small group of hardcore movie nerds, but on his home turf he was a big deal. Nevertheless, he had a troubled relationship with his government (which, in its way, honestly wasnít a whole lot less repressive than that of the North in those days), and it was looking increasingly like his career was pretty much over. Thatís when Kim Jong Il, son of North Korean Great Leader Kim Il Sung, entered the picture. The younger Kim has always had a reputation as a movie nut, and has even written a book on the philosophy of communist filmmaking. In the 70ís, one of his jobs was overseeing the Northís popular culture, and it appears to have bothered him immensely that his own country didnít have even a single director who could compare with Shin Sang-ok down south. So with Kim Il Sungís blessing (or maybe it was the old manís idea in the first placeó I told you Iíve been having a hard time pinning down the details), Kim Jong Il had both Shin and his wife kidnapped and brought across the DMZ.

You might expect Shin to have been put to work making movies immediately, but thatís apparently not quite the way it happened. His dealings with the two Kims were understandably strained, and he eventually wound up in a prison camp, where he spent about five years. Then in 1983ó and who am I to attempt to understand how a dictatorís mind works?ó Shin was released from prison and brought before Kim Jong Il himself. The Great-Leader-in-Training had a job for Shin, one for which he believed only the captive director was suitable: Kim wanted someone to make him an epic socialist monster movie! And because he was the son of the Great Leader, he was in a position to make certain Shin got whatever he needed to deliver it. First pick of the countryís rather backward and inadequate film-industry infrastructure? Easy. Enough money to bring Tohoís special effects people over from Japan to build the monster suit and miniature sets? Can do! Squads of actual soldiers to serve as extras in the battle scenes? No problem! And by every indication, Shin was surprisingly devoted to the project, even to the extent that when he finally escaped from Kimís clutches, he shot a remake of Pulgasari for the free world. But even an artistís devotion has its limits, and Shin was not about to forego a chance to flee the country just so that he could put the finishing touches on a movie. When opportunity knocked in 1985, Shin and his wife skipped town immediately, leaving Pulgasari to be completed by a different director. Maybe it was the escape of its creator that turned the Kims sour on Pulgasari, leading them either to ban it or to allow it to languish unseen for some thirteen years. Or maybe there was something in the content of the movie itself that offended them. Sure Pulgasari tells the story of a peasant revolt in the middle ages that is aided by the power of an indestructible monster, but thereís more than one political spin you could put on a movie in which the downtrodden rise up against a cruel tyrant who starves them in order to build up the most powerful army his limited resources can buy. And even if you donít make the connection that the movieís evil king could represent North Koreaís current leaders just as easily as its old ones, thereís simply no getting around the point that Pulgasari depicts the peopleís savior in the fight against tyranny turning into their own worst enemy once that tyranny has fallen. So perhaps thatís why what is probably the worldís only communist kaiju flick ended up vanishing off the face of the earth between the time of its completion and its own breakout across the DMZ in the late 1990ís.

As for the movie itself, itís the fourteenth century, and tensions between the peasants and their overlords have given rise, as usual, to an army of bandits roaming the mountains, preying on agents of the king (Pak Yong-hok). Itís all a big secret, of course, but the leader of these rebels is a man named Inde (Gi Sop Ham), who works as an apprentice to Takse the blacksmith (Ri Gwon). One day, the royal governor (Pak Ping-ilk) drops in at Takseís village with a work order for the blacksmith. With Indeís bandits running around in the mountains, the governor feels his men need to be better armed, and so he has commissioned Takse to make him some weapons. Thereís a double dilemma for the blacksmith involved here, because not only is Inde (whose double life Takse knows all about) his apprentice, but the rebel leader is also betrothed to his daughter, Ami (Son Hui Chang). At first, Takse figures he can weasel out of his jam by saying heís all out of iron, but the governor has an answer to tható he sends his men around house to house to confiscate the villagersí farming implements and iron cookware.

Indeís not going to stand for that kind of crap, however, and he and his bandits swoop down upon the soldiers to give them what-for. There are too many soldiers, though, and theyíre too well equipped. Inde and his top henchmen are captured, and Takse is jailed right along with them. Ami and her brother, Ana (Ri Jong-uk), hear about the menís plight, and become particularly distraught when they learn that Takse is being kept without food on the theory that he, an old man, will break first and tell the governor everything he could want to know about the rebels still remaining at large. The blacksmithís children sneak some rice to him, but by then itís too late. Takse realizes that heís at deathís door, so instead of eating the rice, he mushes it up into a wad a little smaller than a womanís fist, and sculpts it into an idol. He dies with a prayer on his lips.

The little idol is among the personal effects that Ami and Ana collect from the prison the next day. At first they figure their dad just meant it as a keepsake for the children heíd leave behind, but then Ami has a minor accident that changes the picture entirely. While repairing her brotherís torn shirt, Ami accidentally sticks herself with the needle, and a drop of her blood falls directly onto the little idol. The tiny creature suddenly comes to life, and begins eating the girlís spare sewing needles! So of course the two orphans adopt the thing as a pet. And recalling an old legend their father once mentioned about an iron-eating monster, they dub the goofy little critter ďPulgasari.Ē

What Ami and Ana donít realize is that Pulgasari grows whenever he eats iron. They get the hint the next day, though, when they notice that their new pet is missingó along with just about every ferrous object in their shackó and discover that he is now several times his original size once they track him down. The monsterís iron-eating habit soon puts itself to practical use when Pulgasari gatecrashes the public execution of Inde and his men, and eats the blade of the headsmanís sword before he has a chance to do anything with it. And as Pulgasari grows larger, he eventually becomes powerful enough to enable Indeís rebels to storm the palace of the royal governor and drive all of the kingís representatives out of the province. That gets the kingís attention, no two ways about it. Sick to death of dealing with rebellious peasants, the king sends his most capable military commander, General Fuan (Ri Riyonun), to the offending province to restore order. Fuan might have succeeded, too, if it had been just an ordinary peasant uprising. A peasant uprising supported by an ever-growing monster of phenomenal physical strength and with no apparent vulnerabilities is another matter, however, and one inspired scheme after another fails to destroy Pulgasari or quell the revolt. Even when Fuan hires the most brilliant engineer in the land to invent cannons for him, all resistance to Pulgasari is futile. The kingís armies are overrun, and the tyrant himself dies when the monster destroys his palace. The troubleó at least as far as the newly liberated peasants are concernedó is that Pulgasari still needs iron to eat, and with no war on, they can no longer feed him on captured weapons and armor. Now theyíre right back where they started, having to give up the iron contrivances with which they earn their living in order to support the most powerful fighting force on the Korean Peninsula!

The tricky thing about analyzing movies made in an essentially closed society like North Korea is that itís hard to know how much weight to give apparent influences. In the case of Pulgasari, it seems reasonable to conclude that the resemblance it bears to Daieiís Daimajin trilogy is not accidental, and that it is no coincidence that the numerous battle scenes have much of the flavor of a Hong Kong swordsman film from the 1960ís. But what are we to make of what look like echoes of Paul Wegenerís The Golem? Of the distinctly Italian quality of the background music? Is it realistic to conclude that Shin Sang-ok or screenwriter Kim Se Ryun had seen and were influenced by a silent German monster movie from 65 years back, or that composer Jong Gon deliberately scored this movie to sound like the work of Goblin? In any event, Pulgasari is well outside the mainstream for Asian monster movies, as its setting alone would suggest. For one thing, Pulgasari himself really isnít the focus of the story. Instead, this is more of an old-fashioned epic that just happens to have a giant monster in it, and viewers who come in expecting a conventional kaiju flick are likely to leave disappointed. Nevertheless, there are intriguing parallels between it and the spawn of Godzilla: King of the Monsters, particularly in the efforts of General Fuan to find a technological counter to the monsterís power. And on the subject of Godzilla, the partnership with Toho paid off rather well. The monster suit (inside which is Kenpachiro Satsuma, the same man who plays Godzilla in the Heisei series) is at least as good as the one from Godzilla 1985, and the miniature work is also very skillfully handled. What doesnít work too well are the matte shots; theyíre not quite as bad as the ones in Yongary, Monster from the Deep, but neither do they indicate that the state of that particular art in Korea had advanced all that much in the intervening twenty years. In the end, Pulgasari is more a curiosity than anything else, and all but the truly obsessed can safely miss it. On the other hand, the truly obsessed are likely to ask far more of it than it is capable of delivering, but itís a little easier to appreciate if you look at it not as a kaiju movie, but as a swordsman flick that has a kaiju in it.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact