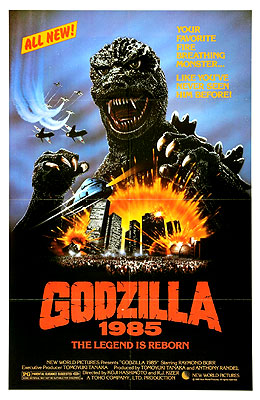

Godzilla 1985 / The Return of Godzilla / Gojira 1984 / Gojira (1984/1985) *½

Godzilla 1985 / The Return of Godzilla / Gojira 1984 / Gojira (1984/1985) *½

I remember when this movie came out. I was ten or eleven years old at the time, and already a lifetime kaiju eiga junkie. I had never seen any of the movies in the theater, though, for reasons that will become obvious if you look at the release dates of the old films while keeping in mind my age in the mid-80’s. I had no real concept of the age of the Godzilla series in those days, but I was aware that the movies were all old, and if you had told me that most of them were far older than I was, I wouldn’t have been a bit surprised. So imagine how cool it was to see theatrical trailers for a new Godzilla movie! You bet your ass I rushed out to see it, and as I recall, I liked it, but I came out a bit confused. You see, I thought of Godzilla primarily as a good guy. For whatever reason, I looked at Terror of Mechagodzilla / Terror of Godzilla / Mekagojira no Gyakushu as the archetypal Godzilla flick, and I was in any event far more familiar with such late-period good monster vs. bad monster wrestling matches as Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster / Gojira tai Hedora than I was with the earlier Godzilla-as-A-bomb-proxy approach. What I didn’t realize, and wouldn’t have fully understood even if I had known, was that Godzilla 1985 / Gojira 1984 / Gojira is as much a remake of Godzilla: King of the Monsters / Gojira as it is a sequel, and that, to the extent that it is a sequel, it is a direct one-- for the purposes of this movie, Gigantis the Fire Monster / Godzilla Raids Again / Gojira no Gyakushu and all of the other movies up to and including Terror of Mechagodzilla never happened.

It is thus not surprising that Godzilla 1985 begins, like its illustrious predecessor, with a fishing boat out of control on a stormy sea, the current carrying it inexorably toward a deadly outcropping of jagged rocks. Just before the boat would have run aground, the pile of rocks explodes into a blinding burst of fire. In the next scene, we learn what happened. Another boat, this one a small, sailing pleasure boat, approaches the drifting trawler. The new boat’s single occupant (Ken Tanaka) has heard on the radio that a fishing vessel has been lost, so he decides to go aboard and see if this could be the one. He is wholly unprepared for what he finds, however. All but one member of the boat’s crew is dead, their bodies discolored and desiccated in what was, at the time, a fairly common popular representation of radiation poisoning. The sole survivor (Shin Takuma, who would return to the series almost two decades later in Godzilla Against Mechagodzilla) seems to be in shock, but he fortunately comes around in time to save his discoverer from being eaten by what looks like a sand flea the size of a great Dane.

It turns out that the sailboat guy is a reporter (New World Pictures did a terrible job identifying the characters when they dubbed the American version, and I thus have absolutely no idea what anybody’s name is in this movie-- expect to see lots of references to “the Reporter” and “the Last Fisherman”), but his remarkable scoop ends up doing him little good. The fact that the crew was killed by radiation poisoning out at sea has given some important people the idea that Godzilla has returned, and they Don’t Want To Cause a Panic. In fact, the government is trying so hard to keep a lid on the story that they are even keeping the survival of the Last Fisherman a secret from his sister (Yasuko Sawaguchi, of Princess from the Moon and Orochi, the Eight-Headed Dragon), his only living relative. The Reporter and the Fisherman’s Sister cross paths because she works for the Inevitable Scientist (Yosuke Natsuki, from Private Lessons II and Ghidrah, the Three-Headed Monster), whom the Reporter has been given permission to interview-- in essence, he’s allowed to go on researching his story, but not to have any resulting articles published. The Inevitable Scientist (whose family died in Godzilla’s last visit to Tokyo) has figured out that Godzilla is active again (don’t ask me how), and he is now devoting all of his energy to finding a way to keep him away from Japan.

Obviously, there are just too many coincidences here for any secrets to survive long, so it comes as no surprise when the Reporter blabs to the Fisherman’s Sister that her brother is not only alive, but that the Reporter has himself seen him. It turns out not to matter much, though, because Godzilla puts in an appearance at a nuclear power plant shortly thereafter. It’s a sad testimonial to the quality of this film to point out that it actually rips off Gamera/Gammera the Invincible/Daikaiju Gamera here by having Godzilla essentially eat the plant’s reactor-- Godzilla has become a fuel-eater like his bastard cousin over at Daiei. Then, in a development that makes absolutely no sense at all, but which will prove to be an indispensable plot device, a flock of seagulls flies overhead, and Godzilla turns away from the power plant to follow them.

And now begins the subplot that could have made this a very interesting movie, if only somebody involved in its creation had given a damn. Despite all the changes that the passage of time had wrought, the 1980’s closely resembled the 1950’s in one important respect-- both were vintage decades for Cold-War tensions. One of Godzilla’s peskier tricks in this early phase of the film is the destruction of a Soviet nuclear submarine. This, of course, lights up a couple of numbers on that “DEFCON” chart from WarGames, and the prime minister of Japan finds himself in the unusual position of stopping a nuclear war by telling the leadership on both sides that it was Godzilla that caused the problem. From this point on, events in the film will play out against a backdrop of tension caused by trigger-happy superpowers who’d like very much to nuke Godzilla, writing off the thousands of Japanese casualties that would inevitably result as “collateral damage.”

Which leads us, in a roundabout way, to a feature of this film that would resurface from time to time throughout the course of subsequent sequels, the presence of multiple groups pursuing parallel strategies to defeat Godzilla. While the American and Soviet militaries look for opportunities/excuses to nuke the big lizard, and the Inevitable Scientist and his assorted sidekicks look for a way to lead Godzilla into the crater of an active volcano by isolating whatever frequency it was in the calls of those birds that got his attention, the Japanese military unveils the first in a series of super-secret super-weapons that it just happened to have lying around-- in this case, a high-tech aircraft called the Super-X (how imaginative). Actually, “aircraft” is maybe the wrong word, in that it suggests something that resembles a plane in some way. The Super-X kind of looks like a flying bicycle helmet, if you want to know the truth, and I have a damned hard time imagining how it could work. The idea behind the anti-Godzilla plan involving the Super-X is to arm it with cadmium-warhead missiles; cadmium supposedly shuts down nuclear chain reactions, or some such nonsense, and it is hoped that it will do the same to Godzilla’s vaguely reactor-like metabolism. When Godzilla at last makes his entrance into Tokyo, all three plans spring into action at once, at cross-purposes to each other. The Inevitable Scientist’s lab is nearly destroyed in the fighting, the Russians launch a thermonuclear missile at Tokyo, requiring the Americans to fire one of their own to shoot it down, and the Super-X’s apparent victory over Godzilla is negated when the creature is restored to full strength by the fallout from the resulting nuclear explosion in the upper atmosphere. In what may be the best moment in the film, Godzilla gets his revenge on the Super-X by toppling a skyscraper onto it after forcing it to land. Finally, as if there were any other possibility, the Inevitable Scientist and the Last Fisherman set up their chirping-birds device, and lure Godzilla into that volcano in a scene that tries, but fails miserably, to re-create the bizarre poignancy of the monster’s death-scene from the original movie.

Jesus, what a mess! This, the first of the Heisei Godzilla movies (the term refers to the fact that most of them were made during the reign of the new emperor-- Japanese imperial reigns are always called by specific names, rather than being referred to as “the reign of the Emperor Whomever,” and the current one is called the Heisei) demonstrates that the movie-making strategy so popular with American studios-- if the movie sounds like it’s going to suck, throw more money at it-- is neither entirely peculiar to Hollywood, nor any more viable when transplanted out of its native soil. The fact that the special effects here are better than they were in the 70’s Godzilla flicks is about the only kind thing I can think of to say about Godzilla 1985. And even here, there is a major caveat, to wit: the new Godzilla suit, which resembles a fairly straightforward cross between the 1954 and 1974 suits, retains rather too much of the 70’s-era cute-and-fluffy look. It doesn’t matter how scowly Godzilla’s brows are when the face beneath them is shouting, “come pet me!” so loudly.

The defects with the rest of the movie are a little harder to nail down, partly because it’s difficult to figure out how to apportion the blame. You see, US distributors New World Pictures did to Gojia 1984 something like what the “Godzilla Releasing Company” did to the original Gojira back in 1956. That is to say, they drastically re-edited the movie and dropped in a whole bunch of new footage starring Raymond Burr. Unfortunately, it is quite obvious that New World didn’t put nearly as much thought into how they were going to integrate these new scenes into the existing story as their counterparts had 30 years earlier. You’ll notice that my synopsis above doesn’t even mention Burr’s reprisal of his role as reporter Steve Martin. This is because his scenes affect the story not at all, nor is he even made to be present during scenes that do. Whereas the original Godzilla: King of the Monsters went to great (and sometimes laughable) lengths to make it seem like Burr was a part of the action in footage shot some two years previously, the Steve Martin of Godzilla 1985 just stands around looking fat in front of a Dr. Pepper machine in a cheap-looking control room. (By 1985, Raymond Burr was himself nearly as big as Godzilla.) If New World’s people treated the original Japanese footage as cynically and uncomprehendingly as they did their own work, Gojira 1984 might play like an entirely different movie. In light of the muddle-headedness of subsequent Godzilla movies, though, I hardly think that New World is solely responsible for this tawdry spectacle. The logic and motivation problems that would plague Godzilla vs. Biolante and its successors are already on display here (why, for example, would Godzilla be instinctively programmed to follow seagulls around?), as is the sketchy, haphazard characterization that is the Heisei movies’ stock in trade.

Finally, there is the musical score, which, especially in comparison to that of the original Godzilla: King of the Monsters/Gojira, is almost offensively bad. Ifukube’s magnificent themes are nowhere to be found here, their places taken by a series of musical cues plagiarized from a wide array of more or less inappropriate sources. The score for Godzilla 1985 shamelessly rips off music from Star Wars, Friday the 13th, and even “Dragnet,” and does so in such a way as to suggest that the filmmakers thought we would be too dense to notice. Whatever their defects, I can at least honestly say that the next round of Godzilla films would be better than this.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact