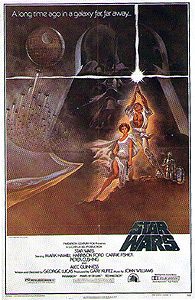

Star Wars/Star Wars, Episode IV: A New Hope (1977) ****

Star Wars/Star Wars, Episode IV: A New Hope (1977) ****

Yes, I know. Writing up Star Wars in 2013 is an insane, stupid idea, especially given the way I normally review movies these days. There’s no way I could do justice to a pop-culture game-changer of this magnitude in three to six pages; hell, it would take me years just to do the background research necessary to try. Consider this, though— there was a time when Star Wars was not yet a vast multimedia empire, when it was not yet the foremost corporate money-spinning machine in the entertainment universe, when it was not yet the de facto religion of a third of English-speaking sci-fi nerddom. There was a time, in other words, when Star Wars was just a goddamned movie, and not even one for which the studio heads had high expectations, at that. Seriously, you know what the folks in charge at 20th Century Fox thought was going to be their runaway hit for the summer of 1977? The Other Side of Midnight. That’s right, they figured a Sidney Sheldon adaptation would be the blockbustingest blockbuster of the year, and what’s more, enough theater owners agreed with them that Fox wrote into The Other Side of Midnight’s rental contract a clause requiring exhibitors to book Star Wars, too, as a prerequisite for screening the Sheldon picture. Funny how easy it can be to misjudge the zeitgeist, isn’t it? Anyway, the point is, I’m just barely old enough to remember when Star Wars was merely that thing the American Graffiti guy did when he couldn’t get the remake rights to Flash Gordon, and I think maybe the most interesting way to look at Star Wars today is to forget about all the accretions of the past 36 years, and to try to get into the mindset of those first-run audiences. That’s what I aim to do here, so if at any point as you read this, you find yourself thinking something like, “But Timothy Zahn and Dave Wolverton addressed those issues with their stories in Tales from the Mos Eisley Cantina!” then kindly refrain from writing in to bug me about it.

A long time ago, a galaxy far, far away is ruled by a despotic empire that used to be a relatively benign republic. Students of ancient Europe will perhaps have heard that one before somewhere. Like many despotic empires, this one has been contending of late with a rebellion that enjoys broad-based popular support, and whose leaders exercise effective control over much nominally imperial territory. The government (again in the usual manner of empires) has responded to the rebels’ rising fortunes with terrorism on an epic scale. Specifically, the imperial military has constructed a moon-sized mobile space fortress with firepower sufficient to obliterate entire planets. When this Death Star comes online, its commander, Governor Tarkin (Peter Cushing), will be able to destroy rebel strongholds at will— which is to say that he’ll be able to impose such a high price on rebel sympathies that no one in the galaxy will dare act upon them.

Fortunately, a highly-placed rebel agent— Princess Leia Organa of Alderaan (Carrie Fisher, from Sorority Row and the “Broadway on Showtime” version of Frankenstein)— has obtained detailed plans to the Death Star through her network of spies. The hope is that analysis of the plans will reveal a weakness in the empire’s terror machine, and Leia is currently racing toward her homeworld to hand them over to somebody who is presumably better trained in sorting out the implications of blueprints than she is. Her ship is intercepted, though, near the lawless desert planet of Tatooine by an imperial task force under the command of Darth Vader (David Prowse, of The People that Time Forgot and Jabberwocky, with an uncredited James Earl Jones supplying his voice), a mysterious figure unaffiliated with the regular military, who functions essentially as the Emperor’s personal attack dog. Leia is captured, but not before she transfers the Death Star plans to the memory banks of a robot called R2-D2 (Kenny Baker, from Time Bandits and Circus of Horrors, unrecognizable inside what amounts to a big, metal barrel, and with his dialogue electronically converted into streams of high-pitched beeps). Dragging another droid designated C-3PO (Anthony Daniels, of Conjure and I Bought a Vampire Motorcycle) along with him, R2-D2 boards an escape pod and blasts off for Tatooine, where Leia directs him to entrust the plans to someone by the name of Obi Wan Kenobi.

Once on the inhospitably arid world, the droids quickly fall into the hands of a tribe of Jawas, dwarfish, nomadic creatures who support themselves by scavenging, reconditioning, and selling the technological detritus of Tatooine’s more advanced societies. This particular tribe specializes in used robots, and they sell R2-D2 and C-3PO to Owen Skywalker (Phil Brown, from Weird Woman and Maneaters Are Loose!), a human farmer living on the outskirts of a settlement called Tashi Station. Owen and his wife, Beru (Shelagh Fraser, of Doomwatch and The Body Stealers) have a 20-ish nephew named Luke (Mark Hamill, from Village of the Damned and Guyver) who wants nothing more in life than to get the fuck off of Tatooine. He’s even ready to join the military if that’s what it takes, his loathing for the empire notwithstanding, and the academy would probably be happy to have an amateur pilot of his ability. So you can imagine what goes through Luke’s mind when his pre-harvest tune-up of R2-D2 accidentally triggers part of the recorded message from Princess Leia that the droid was supposed to deliver to Obi Wan Kenobi along with the Death Star plans. I mean, here’s a bigger adventure than the boy ever dreamed of, hovering just beyond his reach. Furthermore, Luke thinks he might even know who Obi Wan Kenobi is. Out in the wilderness where the fearsome Sand People roam, there’s a human hermit who calls himself Ben Kenobi (The Man in the White Suit’s Alec Guinness). But before Luke can gin up an excuse to introduce Kenobi to the droids, R2-D2 takes matters into his own hands, sneaking off into the wasteland under cover of night. Luke and C-3PO go looking for him at first light, but get ambushed by Sand People just moments after finding the runaway robot. Then comes a stroke of double good fortune. Not only does someone happen along to drive off their attackers, but that rescuer is none other than Ben Kenobi— who is indeed the same person as Leia’s Obi Wan.

As Kenobi explains back at his hermitage, the reason the rebellion is currying favors from an eccentric old recluse is that he is among the last of the Jedi Knights. The Jedi were the elite peacekeeping force of the Old Republic, martial artists skilled in the use of the Force— the energy field created and sustained by all the living things in the universe. You can think of Kenobi’s old order as the Knights Templar, the Shaolin monks, and the Green Berets, all rolled up into one institution of righteous badassery. The father Luke never knew was also a Jedi, incidentally. So, for that matter, was Darth Vader, which is the reason Kenobi is hiding out on this crummy little rock in a star system nobody cares about. You see, the Force has a Dark Side, which Vader embraced as a shortcut to power both political and metaphysical. His contribution to the Emperor’s coup was to exterminate the Jedi Knights, Luke’s dad included. Kenobi is thus a natural ally for the rebellion, and he thinks Luke would be, too, as the son of a Jedi. It’s exactly the kind of break the kid’s been yearning for, but he doesn’t see how he can possibly take it with his aunt and uncle counting on him for the harvest that’s about to begin. Then a platoon of imperial Stormtroopers takes the decision out of his hands. It didn’t take Vader’s people very long to figure out that Leia must have jettisoned the Death Star plans in one of her ship’s escape pods, and once the troops on the ground found the droid tracks leading away from the pod, it was easy enough to follow them to the Jawas. The Jawas, in turn, pointed the soldiers toward the Skywalker family. By the time Luke comes home from Kenobi’s place, Owen and Beru are dead, and the whole farm is a smoking ruin. Right, then. Rebellion and Jedi apprenticeship it is.

Kenobi, Luke, and the droids travel to the Mos Eisley spaceport in search of a ship to take them to Alderaan. In one of that rough town’s rougher bars, they meet a human freighter captain named Han Solo (Harrison Ford, from Blade Runner and The Possessed) and his Wookie first mate, Chewbacca (Peter Mayhew, of Killer Ink and Terror). Solo’s ship, the Millennium Falcon, is one of the fastest on Tatooine, and its crew are no strangers to outfoxing imperial patrols. Han doesn’t work cheap, but Obi Wan is confident that Leia and the rebellion will pay his fee in return for the data in R2-D2’s memory banks. There’s no time to waste before liftoff, though. Mos Eisley is crawling with imperial soldiers and stool pigeons, and Han has enemies of his own. In particular, a gangster called Jabba the Hutt is offering a reward for his capture big enough to inspire every bounty hunter on the planet.

Meanwhile, on the Death Star, Governor Tarkin is finding Princess Leia a real pain in the ass. Neither torture nor drugs can pry out of her the location of the stolen plans or the main rebel base, and he’s just about out of patience. Then the announcement that his battle station is ready for its shakedown cruise gives Tarkin an idea. A doomsday weapon is no good unless your enemies know you have it, so the plan had always been to blow up a planet somewhere as soon as the Death Star was operational. Since Vader arrived with Leia in custody, the governor had been hoping to make that planet the headquarters of the rebellion, but now he’s thinking Alderaan might be a suitable alternative— unless perhaps the princess would like to start talking now? Leia tries to wriggle out of her dilemma by naming Dantooine, a remote, uninhabited world where the rebels used to be based, but Tarkin destroys Alderaan anyway. After all, who would pay attention if the Death Star’s first victim were a planet in the middle of nowhere, with no indigenous population? The Millennium Falcon arrives on the scene shortly after the unprecedented atrocity— just in time to be noticed and recognized as the ship suspected of smuggling Leia’s droids off of Tatooine. A powerful tractor beam pulls the freighter into one of the Death Star’s hangars, after which Darth Vader himself oversees a search of it. Han, Chewbacca, and their passengers are able to escape detection in a set of secret compartments below the main deck, and they even manage to sneak past the hangar guards by waylaying some Stormtroopers from the search party, and appropriating their uniforms. The trouble is, that still leaves them stuck in enemy territory. On the other hand, it also introduces the possibility of rescuing the princess in the event that they can find some way out of Tarkin’s space fortress, and since Leia’s the one who’s supposed to be paying Solo, even he and his Wookie can probably be relied upon to cooperate. Then the hard part can begin— living long enough to get the rebels their Death Star plans, and putting whatever information they contain to use.

It’s weird that in all the years I’ve been doing this, I’ve never had occasion to discuss the Auteur Theory as such, and weirder still that Star Wars of all things is the movie that finally leads me to talk about it. The latter half of that at least will start to make sense shortly, however. The Auteur Theory was one of the big ideas of postwar French film criticism, which subsequently spread to movie critics just about everywhere. It holds that despite the huge numbers of people who end up working in various capacities on any but the simplest film, the role of the director is such that he or she becomes the “author” (or auteur, if you’re French) of the picture for all practical purposes. The Auteur Theory was one of those concepts that become truer after they’re propounded, for it happened to come along just in time for the final collapse of the old Hollywood studio contract system and its authoritarian analogues overseas, and it was expressly designed to encourage directors working in the freer environment of the 50’s and on to try to live up to it. It was hugely influential not just on the French New Wave of the 60’s (unsurprisingly, since François Truffaut was the theory’s leading early exponent), but on the so-called New Hollywood of the 70’s as well. It helps account for the rise of the director-screenwriter as a significant phenomenon, and is almost solely responsible for enabling directors to become celebrities in their own right. Like most capital-T Theories, I think it was overly simplistic in its original form; nevertheless, a version of Auteur Theory isn’t hard to spot in my writing here. The way I see it, for a director to be an auteur is optional. Some of them have the sort of overwhelming creative identity necessary to impress their vision on a film more strongly than all the collaborating and/or competing parties, and some of them don’t. Nor are all auteurs directors. Auteur producers certainly exist (Roger Corman springs immediately to mind), and I wouldn’t rule out the possibility of auteur production designers (Daniel Haller, maybe?), auteur cinematographers (the young Mario Bava?), or auteur special effects maestros (Ray Harryhausen seems an obvious contender), either. Finally, auteur status in my assessment has nothing to do with quality of work, and I believe anyone who ever suffered through the inimitable cinematic travesties of Albert Pyun or David DeCoteau would agree with me.

What all that has to do with Star Wars is that George Lucas in 1977 was a director-screenwriter of the New Hollywood cohort. It would therefore be natural to treat him as the auteur of his most famous film, but a close look at Star Wars intriguingly doesn’t support that. Instead, this seems to be a case study in how the collaborative nature of cinema can enable a movie to rise far above the individual limitations of its creators. Consider Lucas’s script, for starters. It’s some derivative crap, layering an undergraduate reading of Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces over the leavings and scrapings of 40-year-old sci-fi serials, the setup and characterizations from The Hidden Fortress, and a climax lifted whole from The Dam Busters. The dialogue is so bad that Harrison Ford reportedly once protested, “You can type this shit, George, but you sure can’t say it.” The screenplay’s main virtue is almost subliminal, a beautifully elegant story structure that spirals outward at a perfectly balanced pace to reveal steadily more of the film’s universe. As a writer, then, Star Wars shows Lucas to have solid instincts, but very little skill. Nor does this movie present him as a director of much distinction. Star Wars’ most memorable images are mostly special effects shots created in development labs from second-unit material. As for his on-set approach, Carrie Fisher relates an anecdote about Lucas losing his voice one day, leading the cast to joke that they should get him a pair of bicycle horns— one to honk for “faster,” and the other for “more intense,” since those were just about the only instructions he ever gave the actors. According to the Auteur Theory, we should therefore expect Star Wars to be dreary, hacky, and awful, but instead it’s a vivid, engrossing, masterfully efficient movie that shows how powerful escapism can be.

That’s where all the people who aren’t George Lucas come in. It’s where we find Peter Cushing, Alec Guinness, James Earl Jones, and an army of seasoned British character actors, classing up the joint and compensating for the inexperience of Mark Hamill, Carrie Fisher, and Harrison Ford. It’s where we find Hamill, Fisher, and Ford as well, who play off of each other so enoyably that their foibles— Hamill’s stiffness, Ford’s exaggerated smugness, Fisher’s mystifying pseudo-Shakespearean pseudo-accent— don’t get in the way of our wanting to spend time around the three main characters. It’s where we find John Barry and his production design team (including concept artists Ralph McQuarrie and Ron Cobb, who deserve to be as big stars in their field as Tom Savini is in his), John Dykstra and his visual effects unit, and Stuart Freeborn’s makeup department, which between them created a fictional environment that not only awes the viewer with its scope and depth of imagination, but actually looks like people (and other things) live there. It’s where we find John Williams and the London Symphony Orchestra, setting the action to one of the classic film scores of the late 20th century, and making Star Wars feel like something much grander than a hypertrophic Flash Gordon tribute. Even Ben Burtt’s sound effects are a vital contributor to Star Wars’ success, considering how much of the running time we spend listening to the noises made by creatures and machines that don’t actually exist. Obviously Lucas deserves a little reflected credit for all that stuff, too, since he would have been in on the major hiring decisions for the cast and crew. But the point remains that the more you narrow down Star Wars to the elements that can be directly attributed to him as director and writer, the less impressive it becomes. Perhaps that’s why Lucas never sat in a director’s chair himself for 22 years after Star Wars. His real talent was for organization, for putting exactly the right people in exactly the right jobs, and it was as a producer— an executive producer, even— that he found his true calling.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact