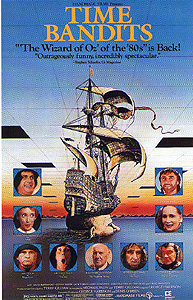

Time Bandits (1981) ***½

Time Bandits (1981) ***½

Sometimes I almost forget that Terry Gilliam was even in Monty Python. After all, it isn’t his contributions to the enterprise that wannabe wits have been quoting into the ground since at least the late 1980’s, and because I haven’t watched either the TV show or the movies in years, that sort of obsessive rehashing has been my main frame of reference for the group’s material for some time. But beyond that, there were plenty of ways in which Gilliam truly was the odd man out in the troupe, and thus relatively easy to lose track of. To start with, he was the lone American on an extremely British team. He also belonged to neither of the group’s main writing partnerships, which consisted of John Cleese and Graham Chapman on one side, and Eric Idle, Michael Palin, and Terry Jones on the other. And accounting for his lack of representation within the repertoires of quote-happy hipsters, he rarely appeared onscreen during the 46-episode run of “Monty Python’s Flying Circus,” and never that I can recall as one of the key performers in a sketch. Yet for all that, I simply cannot imagine the show working without him. Gilliam’s bizarre and instantly recognizable cartoons were the glue that held “Monty Python’s Flying Circus” together; they provided the illusion of episode-wide coherence that made the anarchic absurdism of the individual sketches possible. And so it makes some sense that when the Pythons took their first stab at a proper feature film with Monty Python and the Holy Grail, Gilliam wound up in the director’s chair. Holy Grail would be Gilliam’s only turn in that capacity with all five of his longtime colleagues (all of the subsequent Monty Python movies were directed by Terry Jones), but he alone among the Pythons went on to have a significant directorial career on his own. Jabberwocky, his first non-Python feature, didn’t stray far from either past experience or audience expectations; it plays almost like a monster movie set in Holy Grail’s version of the Middle Ages. Time Bandits, however, was a much bigger departure. Although still a darkly comedic fantasy, it mostly abandoned the misty Medieval squalor of its predecessors to cover every setting from ancient Mycenae to modern suburban Britain, and hiding beneath its sometimes morbid whimsy is an ambitious (if often distracted) meditation on greed, escapism, responsibility, and— of all things— the metaphysics of evil, as seen through the eyes of a spiritually dissatisfied child.

Ten-ish Kevin (Craig Warnock, demonstrating anew that Britain’s juvenile actors have always been, on average, incalculably better than their American counterparts) lives with his mom (Sheila Fearn) and dad (David Daker, from The Woman in Black and I Bought a Vampire Motorcycle) in the British version of the kind of suburb that John Waters satirized in Polyester around the same time. Kevin’s parents lead lives of covetous inanity, accumulating advanced but unreliable kitchen gadgets, lusting after the “fabulous” prizes given away on asinine game shows like “Your Money or Your Life,” and reacting with exasperated bewilderment to their offspring’s voracious intellectual appetites. It’s a frustrating environment for a bright and curious kid, but hey— that’s what growing up is for, right? One night, though, Kevin has an extraordinary experience that makes his day-to-day existence look even more mundane than it did to begin with. Just barely has he drifted off to sleep when he is awakened by a strange rumbling from within his wardrobe. Suddenly, the doors to the armoire burst open, and a mounted knight armed and armored in approximately the style of the First Crusade comes thundering out. The knight leaps over Kevin’s bed, and rides off into what should be the far wall of his room, but has mysteriously transformed into a foggy stretch of primeval forest. Everything returns to normal when Dad storms into the room, demanding to know what all the commotion is about, and Kevin would be inclined to believe that he had dreamed the whole business were it not for one thing. If Kevin was dreaming, then what in the hell was the raucous noise that so disturbed his father?

Kevin’s excitement over this curious turn of events is such that he can scarcely wait for bedtime the following evening. He makes sure he’s well prepared for the knight’s return, too, bringing both a flashlight and an instant camera with him when he finally does bed down— that way, he can definitively establish whether he’s dreaming or awake in the event of a recurrence. No phantom crusaders intrude upon Kevin’s fitful slumber, but something arguably even weirder happens instead. This time, the wardrobe disgorges six oddly attired dwarves: Randall (David Rappaport, from The Bride and Sword of the Valiant), Wally (Brazil’s Jack Purvis), Strutter (Malcolm Dixon), Fidgit (Kenny Baker, of Star Wars and Circus of Horrors), Vermin (Tiny Ross), and Og (Mike Edmonds, from Return of the Jedi and Legend). Immediately upon noticing Kevin, the dwarves pile on and begin pummeling him, as if they were expecting to meet an enemy; they all seem rather flummoxed when they get hold of the flashlight and see exactly whom they’ve been attacking. Presumably they were expecting an agent of the colossal spectral head (Ralph Richardson, of Things to Come and The Man Who Could Work Miracles) that suddenly emerges from the wardrobe behind them, demanding the return of some stolen property. The dwarves panic, but not so completely that Randall (evidently their de facto leader) can’t muster the presence of mind to consult a map of no territory that either we or Kevin recognize, determining thereby that the wall opposite the boy’s armoire conceals a hole in the fabric of reality. They quickly set about opening this portal, and Kevin ends up along for the ride (just how advertently is open to question) when his mysterious guests escape through it.

So who exactly are these small, peculiar people, and just what are they doing dodging in and out of boys’ bedrooms in defiance of all recognized physics? As Randall explains, they were employed up until recently (at least according to their frame of reference) by the Supreme Being— which is to say, that giant, glowing head that pursued them into Kevin’s room. In essence, they were minor functionaries of creation, their efforts devoted especially to elaborating on the theme of trees. They all got the sack, though, when Og invented something he called the pink bunkadoo, which apparently strayed too far off-model for the Supreme Being’s liking. (“Beautiful tree that was. 600 feet high, bright red, and smelled terrible.”) Randall and his fellows considered this an injustice, and in the numinous equivalent of walking off the job with hundreds of dollars’ worth of office supplies, they pocketed that esoteric map on their way out the door. The whole of time and space are represented thereon, but the real draw for the disgruntled dwarves was the fact that the map also shows the locations of all the frayed spots like the one in Kevin’s bedroom. The cartographer’s original aim was to enable other members of the Supreme Being’s staff to locate and repair these temporo-spatial defects, but Randall and the others have something a little different in mind now that the map is in their possession. They mean to exploit this cheat-sheet to Creation’s flaws with a vast robbery spree, plundering past, present, and future for fun and profit.

Anyway, the cosmic hole in Kevin’s room leads to Castiglione, Italy, at the time of its conquest by the forces of Napoleon Bonaparte (Ian Holm of Alien and From Hell). That’s rather a lucky break for Randall’s bandits, in that the Grande Armee will certainly have sacked the shit out of the city, concentrating its greatest treasures wherever Bonaparte has made his headquarters. What better target for the inaugural heist than a place where somebody else has already done the hard work? A further stroke of good fortune concerns what Napoleon is up to when his would-be robbers catch up to him. The conqueror of Italy is in the bombed-out ruin of a huge theater, watching a Punch and Judy puppet show— “That’s what I like!” he exclaims within earshot of Randall’s gang, “Little things hitting each other!” Randall talks the harried and terrified proprietor into putting him and his followers on as the next act, and Bonaparte is so charmed by their slapstick antics that he goes backstage and invites them all to dine with him. Indeed, he goes so far as to make them his new general staff, dismissing his real generals in a fit of drunken pique. All the thieves have to do now is to wait for Napoleon to finish enstuporating himself, and they can clean him out of everything his soldiers have looted from Castiglione. Then it’s off to the next portal, and the next opportunity for lining their pockets at history’s expense.

Ironically, that next portal dumps them out in Sherwood Forest circa 1190. The band of highwaymen who waylay them after doing much the same to a noble couple (Gilliam’s fellow Python, Michael Palin, and Shelly Duvall, from Tale of the Mummy and The Shining) may be readily persuaded to take on seven supposedly experienced new hands, but the dwarves are in for a surprise when they meet the boss of the operation. Robin Hood (John Cleese, seen more recently in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and The Day the Earth Stood Still) blithely assumes that these new recruits mean to donate the huge haul they bring into his camp to the poor of Nottingham, just as he does with the spoils of his own crimes. By the time Randall and the rest catch on to this misunderstanding, Robin Hood has already made dizzyingly great headway toward re-redistributing their ill-gotten gains! And since the Merry Men turn out to be rather more like the Scary Men when you meet them in person, not even the normally bellicose Og and Wally are much inclined to raise a fuss. At Kevin’s urging, they make instead a stealthy retreat from the campsite.

Mind you, none of these activities have gone unobserved, and it isn’t just the Supreme Being who’s been watching. At the center of the cosmos, in the Time of Legends, stands the Fortress of Ultimate Darkness, where Evil (David Warner, of From Beyond the Grave and The Company of Wolves) and his minions are locked up for safe-keeping. Evil takes issue with how the Supreme Being has handled Creation, and his greatest ambition is to remake the universe according to his own fetishistically technophilic proclivities. To do that, however, he would have to be able to leave the Fortress of Ultimate Darkness, and that is currently beyond even his considerable power. But if Evil had the map, he too could take advantage of the holes in space-time, and make his escape. The trick will be diverting its current possessors from their campaign of trans-temporal brigandage, and luring them to his prison. To that end, he reaches out to Og’s tiny mind, and plants the suggestion of a quest for “the Most Fabulous Object in the World.” The Supreme Being intervenes at about the same time, chasing his former underlings through yet another portal, but not before all of them have heard Og’s uncharacteristically ambitious pitch and opened themselves up to temptation.

Actually, there are two portals in play this time, and Kevin finds himself separated from the others. He winds up in ancient Mycenae, where he arrives just in time to witness King Agamemnon (Sean Connery, of Zardoz and Highlander) slaying a minotaur. In fact, it’s Kevin’s sudden appearance at the scene of the battle that enables Agamemnon’s victory, for he distracts the monster (which was handily winning up ‘til then) at a crucial turn in the fight. The king gratefully invites Kevin to return with him to his polis, and to stay as his guest at the royal villa. Agamemnon is apparently childless, and he quickly takes a strong liking to this boy whom he regards as an agent of the gods. And Kevin, for his part, finds in the king exactly the sort of involved, interested, and understanding father-figure that he’s been subconsciously longing for all his life. In particular, Kevin is struck by the contrast between his parents’ insatiable hunger for stuff and Agamemnon’s easy generosity. Here is a man who has (on Kevin’s parents’ terms) everything a person could possibly want, yet he unconcernedly gives it away at the slightest provocation. It doesn’t take long for Kevin to realize that he could contentedly spend the rest of his life in Mycenae, and he is thrilled when Agamemnon announces his intention to adopt him. I don’t see that working out too well in the long run, though, and not just because I remember what’s supposed to become of Agamemnon after his homecoming from the Trojan War. The queen, Clytemnestra (Juliette James), is visibly displeased to see her husband lavishing so much love and attention on a child not her own, and were it not for Randall and his companions’ unexpected arrival in the guise of an itinerant dancing troupe, there’s every chance that Kevin would have had a short, exciting life as Agamemnon’s son. Kevin may resent the rescue, but a rescue it most assuredly is.

The gang’s next stop is the promenade deck of the RMS Titanic (misidentified on a prop life preserver as SS Titanic instead), although clearly not a one among them grasps the significance of that name. Otherwise, it wouldn’t surprise them so much when the ship plows into a huge frigging iceberg and sinks, leaving them adrift on a broken plank without a farthing’s worth of the donations they solicited from the crowd at Kevin’s adoption ceremony. For those keeping score, that makes two troves of historic booty lost to shitty luck, and it seems to be that realization that motivates everyone but Wally (who is starting to rethink the entire premise of his thieving career) to get serious about Og’s Most Fabulous Object in the World. Randall has been pondering the issue ever since Og first brought it up, and he is of the opinion that the incredible whatsit must be hidden in the Fortress of Ultimate Darkness. That would be more convenient than it sounds for seven people who are currently stranded, boatless, in the middle of the North Atlantic, because the Time of Legends isn’t like all the other eras. Since it never really happened in the first place, getting there isn’t a matter of finding just the right time hole. Rather, it’s a matter of faith and willpower; you have to believe your way into the Time of Legends, and it’s of no consequence where or when you are when you do so. Getting there is thus easy enough at this point, even for Kevin. The tough part is surviving the ensuing encounters with its mythical and mostly hostile inhabitants— and that goes double for people who are walking into a trap laid by the personification of all Evil!

Time Bandits takes a while to find its footing. Both weirdly paced and weirdly structured, it defies conventional cinematic storytelling expectations in ways that are not always pleasurable or satisfying. Some indication of the movie’s structural oddity may be conveyed by the fact that I can’t confidently locate the act breaks, or even decide with any certainty how many I should be looking for. This could be an extremely ungainly and front-heavy three-act film, or a five-acter in which the usual functions of acts three and four are reversed, or even a freakishly elongated example of the four-act template favored by television dramas with full-hour timeslots. The pacing puzzlements sort themselves out once Kevin and the dwarves arrive in the Time of Legends, but the first hour or so somehow manages to feel too fast and too slow simultaneously. That’s a real problem whenever Time Bandits is wearing its comedy hat, because timing is essential to effective humor, and it’s hard to have good short-term timing when the long-term pace of the story is off. Fortunately, Gilliam gets his shit together in time to leave a solidly positive impression at the last. The second half of the film is much funnier, much more exciting, much more thought-provoking, and much more visually impressive than the first.

If I had to pick one favorite thing about Time Bandits, it would be the adroit way in which Gilliam toys with what has consistently been fantasy cinema’s most annoying bait-and-switch tactic since the advent of multi-reel filmmaking in the 1910’s. To a careful observer, there’s plenty of evidence from the outset that Kevin is dreaming his entire adventure. All of the historical locations he visits are represented somehow in the collage of photos, drawings, and clipped magazine illustrations on his bedroom wall, and the first time we see Kevin, he’s reading about warfare in ancient Greece. The movie’s depiction of each era is oddly off, as if we were seeing the conceptions of a well-read child rather than any sort of strict reality; this is most apparent in the characterization of Napoleon, with his exaggerated height fixation and his right hand (eventually revealed to be a gilded prosthesis) perpetually tucked inside his vest. The spacecraft Wally brings back from the future when Kevin dispatches the dwarves across the eons to get help for the showdown against Evil is a dead ringer for the Micronauts toy that can be briefly glimpsed in Kevin’s bedroom. If you’re a really big nerd, Randall’s Sherman Firefly tank destroyer in the same scene is unmistakably a toy, too; its tracks are continuous bands of sculpted rubber (real Sherman tracks consisted of separate rubber blocks held together with overlapping steel cleats along their edges), and its drive sprockets are clearly non-functional. Gilliam’s sets-and-props people had to modify the genuine surplus Firefly used for the shoot to make it look like that, so the changes have to be significant. And indeed Kevin does eventually wake up in his own bed. However, when he does so, he has tangible evidence that his extradimensional travels really occurred, in the form of several Polaroids that he took in Mycenae. Nor, as it happens, is his journey quite over yet.

On the whole, Time Bandits turns out to be something that hasn’t been seen with any regularity since at least the 1950’s. It’s a children’s movie designed not merely to be palatable to adults, but to directly address adult concerns on one level even as it engages the juvenile viewer on another. Indeed, I would be tempted to call it a kids’ movie for adults if I didn’t remember so vividly how much I loved Time Bandits as a child. The key point, however, is that although I loved it back then, it’s only now that I feel as though I truly appreciate it, and fully understand what Gilliam was trying to do. In an important sense, Time Bandits is a movie about childhood, and in particular about that vital moment in every perceptive kid’s life when it becomes apparent that adulthood doesn’t automatically confer intelligence, wisdom, or responsibility. At first, Kevin seemingly knows only that he isn’t content. He and his parents relate to each other across a vast gulf of mutual incomprehension, but there’s little indication that the boy has ever consciously thought about what constitutes that gulf. The adventure with the dwarves begins for Kevin as the fulfillment of all his unarticulated escapist fantasies, but as a consequence of his journey across the ages, he comes to understand more clearly what’s missing from his ordinary life. And just as importantly, he comes to recognize that his parents’ materialism is itself an escapist fantasy, and that the escape offered by the dwarves is at bottom just as banal as that offered by game shows and high-tech electric juicers. Arguably the treasures sought by Randall and company are of greater intrinsic worth, but at least the stuff mom and dad spend their lives coveting is potentially useful within the context of their lives. Randall, Wally, Fidgit, Strutter, Og, and Vermin are quasi-immortal beings from a higher plane of existence; what the hell do they need with gold, jewels, and famous paintings? The equivalency is finally fully exposed in the Fortress of Ultimate Darkness, when Evil presents his greedy dupes with the Most Fabulous Object in the World— let’s just say that here is a subject on which Randall and Kevin’s father would be in total agreement. (For that matter, it’s surely no coincidence, either, that Mom and Dad both exhibit a milder form of Evil’s mania for technology.)

The revelation of the Most Fabulous Object in the World also marks a major thematic turning point, for thenceforth Evil eclipses the Supreme Being as the main antagonist. In other words, rather than running away from authority and responsibility, Kevin and the dwarves come up against the thing that authority and responsibility theoretically exist to oppose. Time Bandits does the orthodox thing at that point, demonstrating that for all their courage and resourcefulness, our diminutive heroes are no match for Evil without the help of the Supreme Being, before whose power even the mightiest sub-divine menace is like a stink bug being mildly irritating in your kitchen. Notice, however, that the Supreme Being shows his hand only after Kevin, the dwarves, and the various reinforcements the latter ran off to fetch from this era or that have been soundly defeated, and indeed after said reinforcements have been slain to a man in the fighting. Seeing this go on, and then hearing the Supreme Being remark favorably on the performance of his creation (that is, Evil) leads Kevin to ask the Big Question. You know, the one that all religions positing a benevolent, all-powerful god who both created and governs the universe must grapple with eventually, and to which none of them have ever devised an answer that deserves to be taken seriously: why? For what possible reason would such a deity permit evil to exist, let alone create a being or beings capable of personifying it? The circumstances being what they are, Kevin is in the unique position to put that query to the Supreme Being in person, and the movie’s consistent skepticism toward paternal wisdom resurfaces in a truly breathtaking way. The Supreme Being has no decent answer either! All he can tell Kevin is, “I think… Yes, I think it has something to do with Free Will.” So much for orthodoxy. Indeed, there’s a fair chance that this exchange of dialogue makes Time Bandits the most subversive mainstream-studio movie ever to get a PG rating in the United States.

This review is part of a B-Masters Cabal roundtable devoted to movies in which little people play big roles. Click the banner below to read the rest of the Cabal’s contributions.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact