Alien (1979) *****

Alien (1979) *****

Within the last 30-odd years, it has become extremely difficult to separate the B-movies from the A-movies, and perhaps the biggest reason why is that during the 1970’s— the late 1970’s especially— the major studios suddenly began throwing big-time money at films whose subject matter would in former days have condemned them to tiny budgets, second-string actors, and fourth-string writers and directors. Alien is a prime example of this phenomenon. When United Artists brought a very similar story to the screen as It!: The Terror from Beyond Space in 1958, it was shot in a matter of weeks and budgeted at a few hundred thousand dollars— and as stingy as that was, it represented an unusually great commitment of studio resources to a monster movie for the late 1950’s. Alien, meanwhile, cost a good eight million by the time all was said and done, and was close to two years in the making. Admittedly, some of that budget growth can be accounted for by the runaway inflation of the 1970’s, but even after factoring that in, we’re still talking about a vastly larger production here. And while it’s true that Alien featured no real stars in front of the camera and only one (Carlo Rambaldi, who designed and built the machinery inside the adult monster’s head) behind it, its success made stars of its leading lady, its director, and the most prominent of its three production designers.

This being at least nominally a science fiction movie released during the late 1970’s, it was probably inevitable that Alien would begin the way it does. After an admirably understated main title sequence, we get an onscreen printout identifying the commercial towing vehicle Nostromo, explaining that it is now on its way back to Earth, lugging a mammoth automated refinery crammed with 20,000,000 tons of mineral ore. Then the huge ship and its even huger burden go crawling across the screen from the upper right corner to the lower left, giving the camera a nice, detailed view of their prickly, lumpy underbellies. Hey, it worked for George Lucas, and frankly, it works just as well for Ridley Scott. Inside, the central computer (affectionately known as Mother) has set in motion the routines that bring the seven-person crew out of hypersleep, even though the Nostromo is still untold light-years from home. You see, while the ship was passing through an unexplored star system, Mother picked up a transmission from one of the tiny moons circling the gas giant off to starboard. The transmission is an acoustical beacon— evidently a recording— which repeats at intervals of twelve seconds, and it is in no language or code known to the computer. Quite possibly, it is of non-human origin. Because the crew’s contract stipulates that they will stop to investigate any signal that seems to be the product of intelligence, the Nostromo is going to have to disengage from the refinery and land so that somebody onboard can go take a look. Nobody in the crew, from Captain Dallas (Tom Skerritt, of The Devil’s Rain and The Dead Zone) on down to Assistant Engineer Brett (Harry Dean Stanton, from Repo Man and Escape from New York), is exactly thrilled with the prospect, but as Dallas later tells Third Officer Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) in a slightly different context, they get paid to do what the company tells them to do, whether they like it or not.

To say that the moon from which the signal is emanating is the shittiest vacation spot in the universe would be putting it mildly. There’s pretty much nothing in the air that isn’t poisonous to humans, the temperature is so low that one of the major components of that noxious atmosphere is carbon dioxide crystals, and the weather is as determinedly atrocious as you’d expect from a place where the for-Christ’s-sake fog is made of dry ice. Science Officer Ash (Ian Holm, later of The Fifth Element and The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring) finds it fascinating, and I suppose it is, at that. Of course, the terrain surrounding the source of the transmission is much too rugged to serve as a landing site (that in and of itself would seem to support the crew’s working hypothesis that they’ve come in response to an SOS), so Lambert the pilot (Veronica Cartwright, from Nightmares and the 1978 version of Invasion of the Body Snatchers) is forced to set the Nostromo down some two kilometers away, and even then, the ship takes considerable damage upon making landfall. I’m tempted to wonder if the long walk to their destination has anything to do with why Dallas drafts Lambert to accompany him on the first trip out; the third member of the party, First Officer Kane (John Hurt, of The Ghoul and Frankenstein Unbound), volunteers. The slightly-less-than-intrepid astronauts set off, Ash goes down to the forward observation post to coordinate the mission, and Brett and his immediate boss, Chief Engineer Parker (Yaphet Kotto, from Friday Foster and Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare), get to work repairing the ship. Meanwhile, Ripley, now in temporary command, puts Mother to work deciphering the strange repeating signal, curious as to whether it really is a distress call as they’ve all been assuming. Just after atmospheric interference cuts off communication between Ash and the landing party, the computer cracks enough of the code to suggest that it may be a warning instead.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the source of the transmission proves to be a spaceship, but it’s the weirdest, most fucked-up-looking spaceship Dallas, Kane, Lambert, and probably any other human in the galaxy has ever laid eyes on. The ship has a roughly horseshoe-shaped planform, and it looks to be even bigger than the Nostromo. There is no recognizable propulsion system, no visible sensor or communication antennae, and if it weren’t for the corroded metallic surface of the hull, you’d swear it had been grown rather than manufactured. Dallas and company let themselves in through one of the gigantic, open gangways (which, because they were designed by H. R. Giger, inevitably look more like vaginas 25 feet in diameter than they do like the entrance hatches to a spacecraft), discovering that the ship is, if anything, even weirder on the inside. A spiraling corridor with walls that look like they were constructed out of laminated animal ribs leads to an immense cockpit, which is dominated by the chair in which the giant, fossilized body of the alien pilot still sits— in fact, given the way he and his seat seem to have grown into each other, one doubts whether getting up to leave was ever really an option for him even before he acquired the big-ass hole in his chest which presumably accounts for his death. The really disconcerting thing, though, is that so far as Dallas can tell, the alien’s ribcage was burst open from the inside. A moment later, Lambert discovers a spot where the deck has been melted through, revealing the entrance to some kind of vast, underground gallery— apparently a natural cave which was subsequently extensively customized by some alien civilization. When Kane goes down to investigate, he finds the floor of the cavern covered with hundreds and hundreds of leathery objects about thirty inches tall, roughly the same shape as a bird or reptile egg. Kane gets close enough to one of them to notice that there is something moving inside it, and a moment later, the top of the egg-thing opens up like a flower in bloom. That’s when Kane makes the stupidest mistake of his life: he bends over the egg to look inside, and some kind of hideous thing with eight finger-like legs and a long prehensile tail leaps out and seizes the front of his helmet. By the time Dallas and Lambert get the unconscious Kane back to the ship (where a heated argument between Ripley and the captain over quarantine procedure ends with Ash going against both Ripley and the rules by opening the airlock), the thing from the egg has somehow chewed or melted its way through Kane’s helmet to settle immovably directly on his face.

Ash’s efforts to remove the parasite don’t go well. Prying it loose won’t work because the creature has secreted some kind of resin to glue itself down— pull it off, and Kane’s face comes with it. Nor is severing the gripping legs a viable alternative, for the alien’s blood is so powerfully acidic that just a few milliliters spilled onto the infirmary floor eats through three of the Nostromo’s decks! As Parker puts it, “It’s got a wonderful defense mechanism— we don’t dare kill it.” And even if they did dare, it’s not out of the question that killing the creature would prove fatal to Kane, given that the alien seems to be feeding its host all of his oxygen through the tube which it has threaded down his trachea. After several days of chasing the problem around in circles, however, Ash finds that it has resolved itself; the creature has released its grip on Kane’s face and crawled up into the infirmary ceiling to die. What’s more, not long after the engineers get the ship spaceworthy again and the Nostromo returns to the refinery, Kane regains consciousness, seemingly little the worse for his experience.

This is really just the calm before the storm, though, because while the crew are eating their last meal before climbing back into the hypersleep chambers for the trip home, Kane is seized with convulsions, and a vaguely lamprey-like creature— presumably grown from an embryo deposited in Kane’s body by the thing from the egg— munches its way through his chest and scurries off into the maze of chambers and corridors that comprises the ship’s interior. Naturally none of the survivors wants to go back to sleep with that thing loose on the ship, so the next order of business is to find it, catch it, and stick it in an airlock for final disposal. But as Brett is the first to learn, this sensible plan is easier to formulate than to carry out. By the time he and the alien meet within the retraction well for the ship’s main landing gear, the comparatively diminutive space-lamprey has grown into an approximately humanoid monster more than seven feet tall. It kills Brett and drags him with it into the nearest ventilator shaft, and then sets about the task of doing the same to the rest of the crew, one by one.

Alien exemplifies in a most striking manner the advantages to be gained by making a B-movie on an A-budget, provided the production does not become so large as to get out of control and bring the wrath of the accountants down upon its head. It is nothing if not convincing, and while the funding allotted to it was only rarely enough to pay for the ambitious sets designed by H. R. Giger in exactly the form the artist envisioned, you’d never guess that from looking at the movie itself. Bringing in Giger to work on the otherworldly aspects of the production was absolutely the best decision the filmmakers could have made. The landscapes on the moon, the alien ship and its dead pilot, the various stages in the life cycle of the titular monster— none of them look like anything that had appeared in a movie before 1979, and despite a quarter of a century’s worth of subsequent knockoffs, few of them have been duplicated with any success since then either. The more prosaic sets and miniatures depicting the Nostromo and its towed refinery (devised by Ron Cobb and French underground comics legend Moebius) were just as groundbreaking, albeit in a different way. On the outside, the Nostromo displays a certain kinship with the spaceship designs of Douglas Trumbull and John Dykstra, but no previous sci-fi film that I know of had ever given its spacecraft such functional, utilitarian interiors— or such claustrophobic ones. It seems such a simple thing, but consider: how many computer keyboards have you seen on the bridges of spaceships in movies made before 1980? How many cockpits featuring anything close to the insane profusion of indicator dials and toggle switches which festoon the control panels of even the simplest present-day commercial airplanes? How much piping or wiring or ductwork snaking out from the engineering section? Alien woke people up to just how little the insides of earlier cinematic spacecraft had resembled anything but movie sets, and if you’d been in Hollywood on the night of its premier, you might have heard a resounding *Thwapp!* as thousands of foreheads were smacked in unison, followed by a thundering chorus of “Why the hell didn’t we think of that?!” As with the Giger designs, Cobb and Moebius have been copied repeatedly in the years since Alien, but rarely to much avail— the combination of genuine imagination plus respectable money is tough to match when you’ve only got one of those elements, and is outright impossible to match when you have neither.

Of course, Alien wouldn’t have gotten anywhere without a director who understood what to do with all the lovely toys Giger, Cobb, Moebius, and the artisans working under them had provided. Perhaps the most remarkable facet of the approach Ridley Scott took to this movie is that he was not afraid to take his sweet time in getting the show on the road. If you’ve been reading these reviews for a while, you’ve frequently heard me praise movies that come tearing ass right out of the gate and keep it (whatever “it” may be) coming at a savage and relentless pace until the closing credits. To a great extent, my appreciation for such films stems from understanding that most directors just don’t have it in them to tell a story slowly and methodically without rendering it dull in the process. Scott— at least at this early stage of his career— doesn’t have that problem. Alien is more than half an hour old before Dallas, Kane, and Lambert even set eyes on the wrecked spaceship, and it’s somewhere around minute 45 before the parasite jumps out of its egg and attaches itself to Kane’s face. The all-important difference between Alien and most other conspicuously unhurried horror filims is that Scott uses the downtime rather than letting it sit there as if on the theory that a slow pace will magically create suspense by spontaneous generation. In the prolonged quiet that precedes the grisly birth of the alien larva, Scott very carefully sketches out the personalities of the seven Nostromo crewmembers, digs out the considerable hidden riches of offhand world-building that litter Dan O’Bannon’s screenplay, and establishes the complex web of strengths and weaknesses, amities and antagonisms that underlie the mostly disastrous course of the astronauts’ struggle against their otherworldly hitchhiker. When the shocks finally come— the dinner scene, the ambush of Brett, Dallas’s futilely heroic hunt for the alien in the air ducts— they hit exceedingly hard, and in exactly the sort of escalating manner that the set-pieces in a good horror movie should. And of equal importance, Scott knows exactly when to shift gears. After the confrontation between Ash and Ripley following her discovery of his secret orders from the company sets the endgame in motion, Alien gathers momentum at a steady and rapid clip.

Dan O’Bannon deserves high praise as well. Though we may fault him for his unrelenting (and fortunately unavailing) efforts during the period of principal shooting to force Scott back into the relatively conventional style O’Bannon had envisioned while writing Alien, the quality of his screenplay is exceptional. I’ve already mentioned in passing the many intriguing back-story details which O’Bannon mentions in passing— things like the fact that Earth’s main space-traffic control center is located in Antarctica, of all places, or the strong implication that non-human life (just neither of the species the crew encounters on this particular trip) is already known to exist on other planets. A sufficiently imaginative person could spend hours speculating fruitfully over the hints Alien gives about the universe in which it is set, which is an extremely ironic state of affairs. After all, at bottom, Alien really isn’t out to make us think, but to scare the bejesus out of us by fair means or foul, yet it winds up being far richer as science fiction— or even “speculative fiction,” if you want to be a snob about it— than the majority of the world’s more self-consciously deep sci-fi films. The Alien script is just as good at its main business, too. The characters are fascinating, and are well worth the heavy concentration of B-list talent which the casting department has mustered. Ripley, of course, was the big surprise at the time, a sort of grown-up version of the slasher movie Final Girls who would begin marching in legions upon the world’s movie screens the year after Alien’s release. In 1979, however, her only really obvious antecedent was Halloween’s Laurie Strode, and the injection of such a character into a hybrid of It!: The Terror from Beyond Space, Planet of the Vampires, and Queen of Blood was a brilliantly counterintuitive move— although it must be borne in mind that Ripley, like The Andromeda Strain’s Dr. Leavitt, was originally conceived as a man.

These days, though, I find myself paying more attention to the other characters, the weak ones who are not equal to the challenge which the alien presents. Captain Dallas is especially intriguing. Frankly, he’s not really cut out to command a ship, let alone lead the fight against a nearly indestructible space monster. Running the Nostromo is clearly just a job to him, and quite possibly a job that he’s getting rather sick of. For most of the film, he’s much too soft-hearted and nowhere near brave enough to make difficult, life-or-death decisions, and by giving Ash a plausible excuse to violate quarantine and bring Kane aboard the Nostromo with the parasite on his face, Dallas is ultimately responsible for all the death and destruction that ensue after the ship lifts off from the alien moon. The thing is, though, that Dallas himself seems to understand this, and it’s difficult to see his insistence upon being the one to go into the air ducts to flush the alien out as anything other than a grand attempt to atone for the cowardice and irresponsibility that did so much to get him and his crew into their current fix. I think I might also be the only viewer in the world who is not bothered by Lambert. Sure, she spends the entire movie after Kane’s death teetering on the brink of complete emotional disintegration, but in light of her behavior before the crisis, anything less would be woefully unrealistic. I have a couple of coworkers who are more or less exactly like her, and having seen the way they freak out when the nitwits from the Judicial Information Service break their computers while attempting to install new software, I have no doubt whatsoever that a Lambert-style meltdown would be precisely the result if it ever came out that there was a monster from outer space living in the Maryland State Law Library’s HVAC system.

Pretty much the one thing I don’t quite buy about Alien’s story is the cat. I don’t mind how often Jones gets pressed into service as an engine of false scares, since jump scenes generally have no effect on me one way or the other. I find it rather interesting that he has no apparent fear of the alien, and that the creature leaves him alone on both of the occasions when the two of them cross paths. (I have a theory about that, actually. There’s no clear indication that the creature is eating its victims, and much reason to believe that it wants them only to serve the needs of its curious reproductive cycle. Does it seem likely that there’s sufficient room in a housecat’s body to accommodate a growing alien larva?) For that matter, I have no problem with the oft-griped-about scene in which Ripley takes the gamble of tracking Jones down and collecting him after the decision has been made to kill off the alien by blowing up the ship. For one thing, she’s already primed the lifeboat for launching, fulfilling her obligations under the plan; for another, she’s got all the intercom channels open and broadcasting, so she’ll be able to hear it when her fellow survivors are finished with their share of the escape preparations (or when they get themselves into alien trouble, which is of course what happens instead). But finally and most importantly, if it were me, you bet your ass I’d go back for the cat, at least provided that doing so didn’t put anybody other than myself at risk. No, what gets me about the cat business is that I can’t for the life of me figure out what Jones is doing on the Nostromo in the first place. It’s not like a deep-space ore refinery is likely to have much of a rat problem, and I really can’t see a corporate board of directors which is willing to screw its employees as profoundly as this crew has been screwed by Special Order 937 being sufficiently concerned about their workers’ emotional well-being to provide for pets onboard commercial towing ships. Jones is just about the one thing in Alien which seems to exist for no other reason than that it’s convenient to the plot.

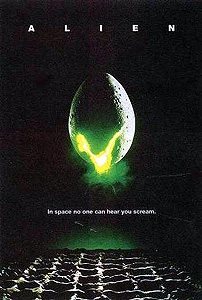

There’s still one thing I haven’t talked about yet, and it’s the aspect of Alien I most want to discuss: the monster. As you all know by now, I’m a life-long monster-lover. I was five years old in 1979— much too young to convince my parents to let me see Alien— but there was simply no way to avoid learning about this movie, or about the creature at its core, while 20th Century Fox’s marketing blitz was underway. Even if you never saw the film, there were the magazine articles, the TV spots, the bubblegum cards (I’ve got a nearly complete set somewhere), the huge and lovingly detailed figure of the adult alien sold by Kenner (I have that, too)— more than enough ancillary materials to saturate the pop-culture environment. I was hooked the moment I saw my first production still, and to this day, I can think of no movie monster more effective. Simply put, the alien really is alien, not just in its appearance, but in every aspect of its biology from its curious interrupted life-cycle to its impliedly silicon-based biochemistry. At every stage of its development, it looks and lives like nothing on Earth, offering just enough hints at familiar anatomical structures and behavioral patterns to make its overall divergence from the familiar that much more disturbing. There is nevertheless an irresistible logic to the creature, a sense that it was indeed fashioned by nature, albeit a nature completely beyond human experience. And incredibly, at no point does it ever come across as a man in a rubber suit. It’s the creature, I think, that raises Alien up from ordinary greatness to that rarefied sphere where only the best of the best may dwell. If so, this must surely be the only case yet seen of a monster giving a movie that special, alchemical impetus.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact