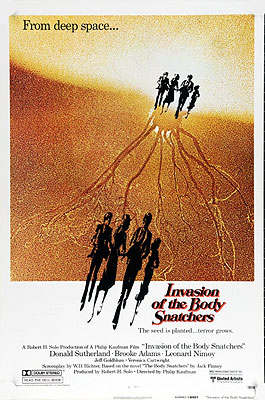

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978) *****

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978) *****

Maybe there was something in the water. Maybe all those years of breathing in the fumes of leaded gasoline had finally started to affect people’s minds. Hell, maybe it was sunspot activity. I don’t know, but whatever the reason, the mid-1970’s saw the beginning of a remake frenzy that didn’t abate until well into the 1980’s. King Kong, Dracula, Nosferatu, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, The Thing— all were remade during this period. And if you want to count radical reinterpretations in with the remakes, the list lengthens to include Frankenstein, The Phantom of the Opera, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and even First Man Into Space. And for whatever reason, this spasm of nostalgia ended up producing quite a few movies of astonishing quality, more than balancing, in my estimation, the drag exerted by such films as Blackenstein or the 1976 King Kong. Philip Kaufman’s version of Invasion of the Body Snatchers is one of these masterworks, surpassing even its already impressive 1956 prototype.

The first big difference you’ll notice between this version and the original is the change of setting. Instead of a small village on the edge of the southern California desert, this Invasion of the Body Snatchers takes place in downtown San Francisco. Matthew Binnell (Donald Sutherland, from Die, Die, My Darling! and Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors) is an inspector for the city health department. We meet him as he goes about the course of his regular duties, completely oblivious to a peculiar, subtle change in the landscape around him: all over the city, small parasitic flowers have begun growing on plants of every imaginable species. No one on Earth realizes this yet, but these mysterious parasites grew from gelatinous spores that had drifted, probably for millenia, across the vacuum of space from some alien world.

Among the first people to notice the plants is a friend and coworker of Matthew’s, named Elizabeth Driscoll (Brooke Adams, from Shock Waves and The Dead Zone). Elizabeth is a dedicated gardener in her spare time, and she realizes that the flowering pods are unusual even before she tries to look them up in one of her reference books without success. Impressed by the strange beauty of the pods, she takes one home and places it in a tumbler full of water by her bedside.

Those of us who have seen the original Invasion of the Body Snatchers know already what a terrible idea this is. And sure enough, the very next day, Elizabeth notices her husband acting strangely. He wakes up much too early, for one thing, and his demeanor is inexplicably secretive, as if he were trying to conceal something from her. And on top of everything else, Elizabeth’s flower is gone.

Unnerved by her husband’s behavior, Elizabeth calls in sick to work the following day and spends her time following him around at a distance instead. Oddly, he never goes to his office, but devotes the entire day to meeting with people Elizabeth has never seen before, exchanging large packages wrapped in heavy brown paper. By evening, Elizabeth is convinced that her husband isn’t really her husband at all, but some sort of imposter. She goes to Matthew with her story, and Binnell scarcely knows what to make of it. He can tell that Elizabeth is scared out of her wits, though, so he suggests that they pay a visit to another friend of his, a psychiatrist by the name of David Kibner (Leonard Nimoy, from Baffled and Star Trek: The Motion Picture). Not in any formal context, mind you— just as friends seeking advice. Kibner has a book signing that night, and Binnell figures that offers as good an opportunity as any to introduce his two friends to each other.

Kibner turns out not to be the only one signing books that evening. Another friend of Matthew’s, a somewhat paranoid poet named Jack Bellicec (Jeff Goldblum, from The Fly and Mr. Frost), is also there, though his book signing isn’t going nearly so well as Kibner’s. Jack and Matthew talk while Elizabeth stands in Kibner’s line, and while she’s waiting for the psychiatrist, Elizabeth overhears a very interesting conversation between Kibner and one of his fans. This woman is frantically telling Kibner that her husband has been replaced by a doppelganger! After the book signing has broken up, it comes out that Dr. Kibner has been seeing tremendous numbers of people suffering from this particular delusion, which he believes is some sort of hysterical defense mechanism for coping with a disintegrating relationship— if a person’s mate is no longer really his or her mate, then he or she need feel no qualms about breaking up with the “imposter.” Elizabeth, naturally, doesn’t buy this for a second, but even she must admit that it sounds a hell of a lot more reasonable than her contention.

We all know Elizabeth’s right, though, and confirmation comes in the next scene, when the camera follows Bellicec to the sauna and mud bath parlor owned by his equally flaky wife, Nancy (Veronica Cartwright, from Alien and The Birds). Jack falls asleep in one of the saunas, and after all the customers have gone home, Nancy finds a body in the stall next to Jack’s. Now finding a stiff in your sauna is bad enough, but Nancy’s situation is even worse, in that the body she finds seems somehow unfinished. There are no lines on its face, its features are so vague that you’d never be able to describe it to someone if you met it on the street, and every inch of its skin is covered with thin, white filaments that don’t quite look or feel like hair. But for all its nondescriptness, the body somehow resembles Jack. Nancy’s screams wake Jack up, and he instantly calls Matthew Binnell to come over and have a look at the thing in the sauna. Binnell’s examination of the body turns up yet another disturbing detail: the body has no fingerprints! Suddenly, Elizabeth’s story doesn’t sound so crazy anymore, does it?

Matthew doesn’t think so either, and he rushes over to Elizabeth’s place to check up on her. He finds her husband awake, but refusing to acknowledge the doorbell, and so Binnell sneaks around the back of the house, and breaks in through the basement door. When he gets up to Elizabeth’s room a few minutes later, he sees his worst fears confirmed. Lying among the flowers on the balcony outside Elizabeth’s room is a perfect duplicate of her. Matthew just barely sneaks out with Elizabeth without her husband discovering him, and returns to the Bellicec place. By this time, they have called in Dr. Kibner, as per the instructions Matthew gave them on his way out the door. But when Kibner arrives to look at the body, there is no trace of it anywhere. Nor is there any sign of Elizabeth’s double when Matthew foolishly insists on sneaking back into Chez Driscoll with Kibner in tow and calling the police to meet them there to look at Elizabeth’s “other body.” Only Kibner’s formidable powers of persuasion save Matthew from a stay in the municipal jail.

But because Mr. Driscoll is a pod person, there can really be only one explanation for Kibner’s ability to elicit his trust, and before long, it will be obvious to everyone but Matthew, Elizabeth, and the Bellicecs whose side the psychiatrist is really on. Evidently, Kibner brought a quartet of pods with him to hide in the garden the last time he visited Matthew, because on the night after the debacle of the missing bodies, while all four protagonists are staying over at Binnell’s place, those pods sprout, and begin developing into vegetable doppelgangers. If Nancy weren’t such a light sleeper, it would have been all over then and there, but her shrieks of horror awaken everybody in time for Matthew and Jack to destroy the growing doubles. From this moment on, the four will be on the run constantly, as it becomes increasingly clear that the entire city of San Francisco is under the pod people’s control. And as is only fitting for a film made in the pessimistic late 70’s, this Invasion of the Body Snatchers ends not by raising the question of whether humanity will ultimately be able to survive the alien plants’ silent onslaught, but by suggesting an answer to that question: well, no... probably not.

As with its predecessor, paranoia is the name of the game with Kaufman’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers. There is one important difference, though, and I think that difference (along with Kaufman’s ingenious exploitation of that fact that we already know the general outline of the story) goes some way toward explaining this version’s heightened power to get under the viewer’s skin. Unlike the original, it is very difficult to read a political subtext into this version of the story. If there is an allegorical element to Kaufman’s approach, that allegory concerns the unwanted side effects of our increasingly atomized society. This is where the move to the big city comes into play. The great paradox of modern urban living is that you are thoroughly surrounded by other people, and yet those people live lives so completely insulated from yours that you may as well be alone. What Kaufman shows us is that the great hope of the characters in the old Invasion of the Body Snatchers— that everything would be okay if only they could reach a major population center— is utterly false. If anything, the pods’ takeover is helped by the conditions of life in the city. Without the sort of close interpersonal ties that characterize small towns, the pods can do their work without anyone even noticing. The breakdown of the old social fabric is a problem that is still with us to a much greater extent than the sort of grand ideological clashes that Siegel’s version of the story played on, and it is something that touches our lives in a far more personal manner. Meanwhile, that personal quality plays up another angle that was only very vaguely sketched in the original. When we lose our sense of context— whether from an excessive, dehumanizing identification with our own ideals, or from the isolating tendencies of city life— we are well along the road to losing ourselves. Kaufman’s pods threaten to do literally what many of us fear the natural evolution of our society has been doing in a figurative, but no less real, sense for most of the last century. By putting the great promise of progress— that under its influence, we are evolving into a new and higher form of life— into the mouth of one of the pod people, Kaufman confronts us with a question most of us would rather not think too much about: Is that really something we want?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact