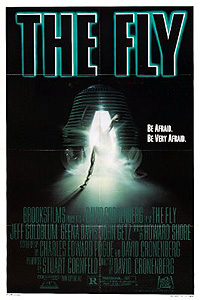

The Fly (1986) ****½

The Fly (1986) ****½

Whatever else it might have been, good or bad, The Fly was hardly a film that cried out to be remade. A minor classic of late-50’s sci-fi, it was fondly remembered, but neither terribly influential nor stocked with much potential for thematic expansion. True, its sequels did take the story in some interesting and even surprising directions, but on the face of it, you’d think the three movies made between 1958 and 1965 had pretty much exhausted the original tale’s potential. David Cronenberg is an extremely crafty guy, however, and if his career has demonstrated anything, it’s that he has a singular ability to dig unexpectedly potent ideas out of apparently hollow— and indeed trashy— premises. As those who know his work could probably guess, Cronenberg’s The Fly is yet another exploration of the director’s favorite theme: body and mind in revolt against their owners with the assistance of advanced technology. And luckily for us, he made it during that phase of his career when he seemingly could not go wrong.

With nary a second spared for setup or introduction, we are immediately confronted with the brilliant but slightly loony Seth Brundle (Jeff Goldblum, from 1978’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers and The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai: Across the Eighth Dimension) chatting up reporter Veronica “Ronnie” Quaife (Geena Davis, who had played alongside Goldblum before in Transylvania 6-5000, and would do so again in Earth Girls Are Easy) at some kind of scientific convention. Brundle claims to be working on a project that will completely change the world as we know it. When Veronica counters that everyone in the convention center says the same thing, Brundle replies with disarming confidence, “Yeah, but they’re lying. I’m not.” Something about the scientist’s odd combination of social awkwardness and unshakable self-assurance gets through to Veronica, and she agrees to go with him to his lab for a look at his mysterious invention.

Honestly, calling it a lab is perhaps a bit too generous. Brundle lives and works in an immense urban warehouse space, some of which he has converted into an apartment, while the rest is given over to his scientific pursuits. The lab itself is dominated by four large electronic devices— three conical metal chambers and the computer terminal that apparently controls them. Veronica is not impressed at first, taunting her host about having invented the phone booth of the future. What she doesn’t realize is that Brundle’s contraption, if successful, really will have just as profound an impact on modern society as the telephone did 100 years before. Brundle’s “phone booths” are really a rudimentary teleportation system, capable of dismantling objects into their component molecules, transporting them through space, and then reassembling them exactly as they had been before undergoing the procedure. The whole business takes only a few seconds, and with enough power driving it, there’s no reason why a Brundle Telepod shouldn’t be able to beam its cargo to just about any spot on Earth. The only snag— and this is why Seth doesn’t want Veronica writing any articles on his system yet— is that while it may work with simple, inanimate objects like the stocking he takes from her to use in his demonstration, the Telepod gear won’t work with living things. Her journalist’s brain buzzing with excitement over the scoop she’s just been handed, Ronnie disregards Seth’s hesitation and rushes off to get in touch with Stathis Borans (John Getz, from Killer Bees), her editor at Particle Magazine.

If Seth Brundle really doesn’t want anyone to know just what he’s up to yet, then Borans’s reaction is a major stroke of luck for him. The editor tells Veronica that she’s been taken in by a petty con-man’s night club magic show, and refuses to have anything to do with the story. As it happens, Brundle shows up at the offices of Particle Magazine to further entreat her not to divulge his secret right after Veronica gets her big brush-off from Stathis. He convinces her to have lunch with him (“I’ve come here to say one magic word to you.” “And what's that?” “Cheeseburger”), and while they’re eating, Brundle attempts to sell her on a compromise plan. Veronica will indeed write the story of the Telepods, but only after they have been perfected. Nor will she write it for Particle Magazine— no, what she’ll be writing is a full-scale book all her own, written from the privileged perspective of an on-the-spot witness to the whole procedure from here on out. It’s too good an offer to pass up, and Veronica accompanies Seth back to his lab immediately to get started.

The first experiment Veronica documents does not go well. The baboon Seth uses as an experimental subject does indeed appear in the receiving Telepod, but there isn’t a whole lot left of it when it does; Brundle thinks the machine might have tried to put the animal back together inside-out. With Veronica around to help him focus his thoughts, Brundle soon hits upon the idea that the computer driving his apparatus is having a hard time with the decidedly non-digital nature of living tissue— rather than reconstruct the baboon as it was, the computer put the thing back together in a way that made sense to it. Having figured out what the problem is, it isn’t long before Brundle has found the solution, and a second baboon reaches the receiving pod in one piece just a few days later. Meanwhile, Seth is enjoying a totally unexpected form of success on another front. His working partnership with Veronica soon evolves into a full-blown romance.

The good times are not destined to last, though, and the reason why is named Stathis Borans. A little rudimentary research convinces Borans that Brundle might really be the genius Veronica says he is; at the very least, he’s got an awfully impressive curriculum vitae. Furthermore, Borans, as Veronica’s editor, might be expected not to like the idea of her writing a book, rather than sharing the glory with Particle Magazine. And finally, as if that weren’t reason enough for Stathis to make himself a big pain in the ass for Seth and Veronica, he also just happens to be the reporter’s ex-boyfriend, and is hence even less pleased with the romantic aspect of the couple’s partnership than he is with the professional. Borans announces his intention to get in Veronica’s way by slipping a package containing a mock-up Seth Brundle magazine cover under the door to the scientist’s lab, where she’s sure to get her hands on it. This she does right when she and Seth are about to celebrate his success with the baboon. When she runs off to the magazine’s offices to confront Stathis, Brundle gets the wrong impression, and starts drinking himself stupid over what he assumes is his new girlfriend’s inconstancy. Between his emotional state and the alcohol, Seth’s judgement decays to the extent that he decides to forego waiting on the results of the baboon’s physical, and make his own Telepod jump right fucking now. Those two factors probably also go some way toward explaining why Brundle fails to notice the housefly that has entered the Telepod with him.

You remember what happened when Andre DeLambre climbed into a matter transporter with a housefly back in 1958. Brundle doesn’t get his body parts scrambled like that, but what happens instead is arguably even worse. Seth appears to be perfectly normal when Veronica comes back to him and explains what she and her ex were really up to. But after Ronnie has fallen asleep, Seth notices that he feels different somehow. For reasons he does not as yet understand, his reflexes, reaction time, strength, stamina, and agility have all been greatly increased. Not only that, it becomes clear over the next couple of days that his personality has changed, too— he has become high-strung, impulsive, extraordinarily talkative, and even more extraordinarily randy. It also seems that Brundle’s metabolism has shot through the roof, for he’s always hungry, and has acquired quite a sweet tooth. At first, Seth thinks he’s stumbled upon an unforeseen benign side-effect of the teleportation process, that something about being disintegrated and then put back together again is “inherently purifying,” but Veronica is not so sure— especially after she notices the strange, stiff hairs that have begun to sprout from his skin. Without Seth’s knowledge, she takes a few to a lab for analysis, with results that seem impossible to everyone but us in the audience: the hairs aren’t human, and if the doctor who looked at them didn’t know better, he’d swear they came from an insect. Sure enough, no sooner has Veronica brought him the bad news than Brundle’s dissolution begins in earnest. Initially, Brundle thinks he’s come down with some exotic form of cancer as a result of the Telepod’s splicing of his genes with those of the fly, but after a little more than a month, he realizes there’s far more to it than that. As Brundle himself puts it when he explains the situation to Veronica, it’s “a disease with a purpose;” it’s changing him into something that’s never existed before.

If I were a reviewer of the allegory-hunting persuasion, I could chew on The Fly for ages, and this is one instance in which that might not be inappropriate. It doesn’t take the desperation borne of English class to see in it a grim metaphorical look at the AIDS crisis. The way Brundle’s body stops working a little at a time during the first month after his trip between the Telepods is strikingly similar to what was, at the time, the nearly universal fate of AIDS patients, and his early guess that his merger with the fly is manifesting itself as a previously unknown form of cancer mirrors exactly the initial speculations of the medical community regarding how AIDS operated. Both Veronica and Stathis immediately become paranoid over the possibility of contagion, in much the same way that the advent of AIDS in America touched off a wave of panic that saw the children of AIDS patients being hounded from their schools, while their HIV-positive parents were subjected to death-threats and vandalism from their formerly accepting neighbors. Consider also Veronica’s reaction when she discovers that she is pregnant, and that Brundle almost certainly fathered the child after his transformation began. Her horror at the possible contamination of the fetus growing inside her (which is dramatized by one of the most viscerally revolting dream sequences in all of moviedom) is strongly evocative of the almost medieval dread that AIDS inspired during the 1980’s. In this light, it is particularly noteworthy that Brundle acquires his “disease” through an impulsive act inspired by romantic jealousy— just as one might contract HIV by cheating on one’s lover out of revenge for suspected infidelity.

I’m not that kind of reviewer, though, so I’m just going to toss the idea out there, and let you make of it what you will. For my purposes, it is enough to note that it’s possible to make that argument with a straight face when talking about this remake of what was, ultimately, just an unusually well-made monster movie. What interests me most about The Fly is not matters of theme (of which I am instinctively skeptical anyway), but rather the way in which Cronenberg builds here upon ideas that seem to have been drawn not from the 1958 The Fly, but from its much maligned second sequel. The Curse of the Fly is, in the US at least, the forgotten entry in the original series. It was made long after the 50’s sci-fi boom had passed from the scene, it performed rather poorly at the box office, and to the best of my knowledge, it has never enjoyed legitimate release on home video. But as I pointed out in my earlier review of that film, it contains the seeds from which many of Cronenberg’s most striking reinterpretations of the story spring. The premise that the Telepod computer is unable to cope with living things is lifted directly from The Curse of the Fly— although the form that inability takes is far more gruesome here. Not only that, the central premise of Cronenberg’s The Fly— that when two creatures are transported simultaneously, the result is their recombination at the molecular level— is hinted at in a scene from the earlier film in which several of Henri DeLambre’s “mistakes” are sent through the transporter together, and appear in the receiving module combined into a huge, undifferentiated mass of writhing, shapeless flesh. It’s a far more astute approach to the subject than the original’s switching of body parts, and Cronenberg’s casting of such bodily assimilation in specifically genetic terms creates the opportunity for something far more horrific than anything the makers of the three earlier films attempted. By making the change genetic, Cronenberg makes it plausible for it also to be gradual, giving his characters plenty of time to explore all the ramifications of their situation.

It might not have made any difference, though, if those characters hadn’t been the interesting, believable, multi-dimensional lot that they are. The Fly is a movie with neither pure heroes nor pure villains, and it is all the better for it. Brundle, though likeable, is noticeably a bit nuts, and would probably be more than a little difficult to get along with in the real world. And of course, the further along his transformation progresses, the crueler and more monstrous he becomes. What starts out as selfish impulsiveness gradually turns deadly, particularly after Brundle realizes that there is a way to cure (or at least minimize) his condition after all. But complicating the picture further is the fact that Brundle is aware of what’s happening to his mind, and tries to take what steps he can to protect Veronica from himself. (Cronenberg’s tremendous knack for chilling one-liners comes out here, when Seth warns his erstwhile lover that her safety depends upon her steering clear of him. His voice cracking as much from emotion as from the rearrangement of his vocal cords, he tells her, “I’m saying I’ll hurt you if you stay.”) It’s very much the same dynamic that was used to such great effect in The Wolf Man, and Jeff Goldblum sells it every bit as convincingly as Lon Chaney Jr. did back in 1941.

Meanwhile, the other two major figures in this drama— Veronica and Stathis— turn out to be just as complex and realistic as Brundle. Most movie heroines in Veronica’s position would be unswerving in their love for and devotion to Seth. But from the moment Veronica realizes she’s pregnant with his child, that love is counterbalanced by a deep-seated repulsion, as it most assuredly would be in the real world. Think about it— how easy would you find it to look past the fact that your lover is at best dying in the messiest, most grotesque possible manner, and at worst turning into a colossal, humanoid bug? Even more surprising is the personality shift that Stathis Borans undergoes when Veronica turns to him to help her cope with what has happened to Seth. He never stops being a jerk, but there’s no question as to whether he really cares for Ronnie, and in his rising to the occasion, it becomes possible to see why she had been attracted to him once upon a time. It isn’t every guy who would face off against a homicidal man-fly for his ex-girlfriend’s sake. And more importantly, is isn't every filmmaker who has the courage to allow a character who has been treated basically as the bad guy throughout to play a major role in defense of the heroine during the climactic scene. The Fly lacks some of the raw intensity of Cronenberg’s early work, but only rarely has he displayed such mastery of characterization as he does here.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact