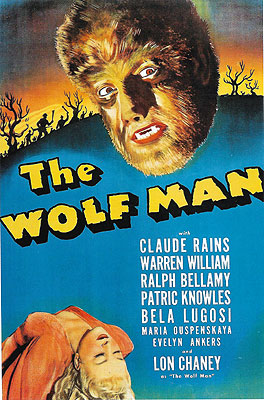

The Wolf Man (1941) ***½

The Wolf Man (1941) ***½

One of the very few acknowledged classics that I have seen from Hollywood horror cinema’s formative years that I think measures up to its reputation, The Wolf Man is also the real source of just about everything Americans today think they know about werewolves. Curt Siodmak, who scripted The Wolf Man, was one of his era’s boldest and most talented B-movie screenwriters. He may not have fit most people’s definition of “artist,” but he produced credible, workmanlike screenplays with fast-moving, engaging plots, sketchy but passable characters, and lots of flashy, distracting bullshit to draw the audience’s attention away from the shortcomings of his work. His script for this film was no exception, and makes a fine introduction to his writing. It has scarcely a dull moment, its mostly stock characters are nevertheless fully sufficient for what the story asks of them, and Siodmak’s wholesale invention of faux-ancient werewolf lore creates the illusion of a far more intelligent screenplay than the movie actually possesses. In short, it’s a nearly perfect vehicle for Lon Chaney Jr., whose style of acting mirrored Siodmak’s style of writing in almost all of its strengths and weaknesses.

Chaney plays Larry Talbot, the estranged son of Sir John Talbot (Claude Rains, from The Invisible Man and the misguided 1943 remake of The Phantom of the Opera), an English nobleman and an accomplished astronomer. As the film opens, Larry has just returned to his childhood home in response to news that his older brother has died, leaving him heir to the Talbot estate. Larry clearly isn’t quite cut out to be a country squire; he’s a sweet-tempered if vaguely oafish man with a great deal of personal charm but not much in the way of intellect or clarity of purpose. The genteel reserve cultivated by his father is almost totally alien to his personality, and indeed this conflict of character had much to do with Larry’s early migration to California, where he made a career of building sensitive scientific instruments whose actual use and function he understood only imperfectly. The younger Talbot’s professional background matters because one of Larry’s first actions upon his arrival at Talbot Castle is to install a new high-powered lens in his father’s telescope, an act that has the effect of putting Larry on the winding road to a very bad end.

After installing the new lens, Larry has a look through the telescope to make sure that all is in order. When he does so, he finds himself inadvertently spying on a beautiful young woman in the town a couple miles distant as she tries on a pair of gold earrings in the form of crescent moons. Larry is instantly smitten, and conveniently enough, a minor downward adjustment of the telescope puts the woman’s address into view. It turns out she lives in the loft apartment above Conliffe’s Antiques, an easy enough place to track down, and Larry immediately sets off to town in the hope of meeting her. The ensuing scene displays to fine effect the dopey affability that Chaney could convey so easily and naturally, and by the time Larry leaves the antique shop after purchasing a silver-headed cane (sound important to you?) from the girl, there seems little question but that Gwen Conliffe (Evelyn Ankers, from The Ghost of Frankenstein and Captive Wild Woman) will be meeting him at closing time, regardless of her protestations to the contrary.

When she does, she has a friend of hers in tow, a girl named Jenny (Fay Helm, of Calling Dr. Death and One Body Too Many). Jenny wants to go to the Gypsy camp outside of town to have her fortune told, and Gwen and Larry both think that sounds like fun. It isn’t. Bela the Gypsy fortune-teller (Bela Lugosi, in the sort of thankless, tiny role that led him to sign the contract with Sam Katzman and Monogram Pictures that ultimately produced such jaw-dropping schlock as The Corpse Vanishes and The Ape Man) sees something in the girl’s palm as he attempts to read it that causes him to cut short the fortune-telling session and order Jenny out of his tent. What Bela sees is a pentagram visible only to him, and as several characters have already told Larry (in rather implausible casual conversation), that is what werewolves see in the palms of their next victims! Meanwhile, Larry and Gwen have wandered off for a walk in the woods, leaving Jenny to hear of her future in peace, and giving Gwen an opportunity to explain to Larry that she’s already engaged to another man. This well-intentioned desertion also has the unexpected side effect of leaving Jenny alone and unprotected when Bela transforms into a wolf, chases her into the forest, and starts chewing her to pieces. Larry and Gwen hear her screams, though, and Larry rushes to Jenny’s aid, clubbing the attacking wolf to death with his new cane. He comes too late to save Jenny, however, and he is rather seriously injured himself in his fight with the beast.

Larry’s wounds, which mysteriously heal overnight, are the least of his worries, of course. For one thing, by the time the police arrive on the scene of his struggle with the wolf, they naturally find Bela’s body beside Jenny’s, rather than that of an animal. And because Larry left his easily recognizable cane behind when Gwen and an old Gypsy woman named Maleva (Maria Ouspenskaya) helped him stagger back home to Talbot Castle, there is evidence tying Larry to the Gypsy’s death. Neither police constable Colonel Paul Montford (Ralph Bellamy, another familiar face from The Ghost of Frankenstein, who was also in Rosemary’s Baby) nor town physician Dr. Lloyd (Warren William) interprets the situation to Larry’s liking or advantage. Both believe that Larry killed Bela, possibly in Jenny’s defense, and Lloyd thinks the incident was such a shock to the normally gentle man’s sensibilities that his subconscious mind has rearranged his memory, replacing the Gypsy with a bloodthirsty wolf. And as the story makes its way around the village, the townspeople increasingly come to see Larry (who, I hasten to remind you, is an outsider) as a rapacious killer, little better than the werewolves of local legend.

Which brings us to the other, and frankly more important, reason why Larry is in big fucking trouble. As Maleva (Bela’s mother, as it happens) helpfully explains when she talks Larry into stepping inside her tent the next evening, Bela infected Larry with his lycanthropy when he bit him that night. And given that the moon is still in its full phase, that means Larry should begin exhibiting the symptoms of his newly-acquired curse as soon as the moon rises. He doesn’t believe the old Gypsy woman, of course, but neither does he fully disbelieve her. Thus, for example, he passes the anti-werewolf charm given to him by Maleva on to Gwen, because “It’ll protect [her]-- just in case.” But there’s nothing to make a man believe in werewolves so effectively as the experience of becoming one, and after his first night out on the town slicing up the unwary, Larry is a true believer of the first order.

His efforts to convince his father and Dr. Lloyd of the danger he poses to the people around him come to naught, however. The wolf tracks near the victims’ bodies are a bit bigger than usual, and the trail they form leads back to Talbot Castle, but not even Colonel Montford, who seems eager to pin something on Larry, is willing to swallow the man’s tales of lycanthropy. Instead, Montford organizes a massive hunting party to catch the wolf (Larry will have to wait), and Sir John hits upon the sensible idea of tying Larry up in his room while the hunt is on, figuring that the posse will catch the animal while his son is restrained, providing thereby incontrovertible proof that he and the wolf are separate beings. Well, it seemed like a good idea at the time. What actually happens is that Larry transforms and breaks free shortly after Sir John leaves the castle to join the hunt (taking Larry’s silver-headed cane with him-- again, do you think this might be important?). Larry the wolf (hey, wait a minute-- that’s the stage name used by the lead singer of a Misfits-wannabe band called the Manimals!) then spends his evening stalking Gwen, finally cornering her in a secluded part of the forest. Fortunately for Gwen, both Maleva and Sir John happen to be headed in her direction when Larry strikes, and Sir John is close enough to the action to repeat his son’s performance from the other night-- with the vital difference that Sir John manages to slay his werewolf without injury to himself, before it can harm its intended victim. Of course, he’s not so happy about the situation after Maleva recites an incantation over the creature’s carcass, and it changes back into his son...

The best thing about The Wolf Man is the way its script plays to Chaney’s strengths as an actor. Truth be told, the man really wasn’t very good, at least if you judge an actor by his range. But those comparatively few things that Lon Chaney Jr. could do he did very well, and Siodmak’s screenplay rarely asks anything of its star that he cannot deliver. Chaney’s Larry is a likeable, affable guy who gets hit with the most horrendous bill of bad luck you can imagine. And because we come to like him so much so quickly, we really do feel terribly sorry for him when he starts growing fur and fangs after his altercation with Bela. Very few werewolf movies before or since have been so successful in winning audience sympathy for the monster. In some cases (The Werewolf, The Curse of the Werewolf) this is because we never knew the character before he came down with lycanthropy. In other movies (Werewolf of London, I Was a Teenage Werewolf), we do get to know the lycanthrope as a normal human, and he’s kind of a prick. Neither of these scenarios offers much chance for strong, sympathetic character identification, and the wolf man’s tragedy is thus diluted. But Chaney needs only three scenes to win the audience over completely, and because he does tortured self-pity every bit as well as he does lunk-headed charm, he needs even less screen time than that to make us feel his subsequent hopelessness and despair. Like all the movies Siodmak worked on, The Wolf Man is squarely in B-territory despite its famous cast and phenomenal success, both financial and critical. But like its star, it finds its greatest virtue in its simplicity and lack of pretense.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact