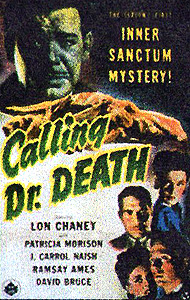

Calling Dr. Death (1943) *½

Calling Dr. Death (1943) *½

In 1930, publishers Simon & Schuster responded to the Great Depression by launching a spin-off imprint called Inner Sanctum. The Inner Sanctum books were all paperbacks, retailing for between half and one-third the price of a regular Simon & Schuster hardcover. Contrary to what is often assumed today, Inner Sanctum did not devote itself exclusively to mysteries or thrillers (there were Inner Sanctum editions of Tolstoy and Walt Whitman, for example), but it was in those genres that the imprint really made its mark. Inner Sanctum’s mysteries were so successful, in fact, that NBC reached an agreement with Simon & Schuster in 1940, according to which the broadcasting company would be permitted to use the publisher’s name for a weekly radio show with an emphasis on mystery, suspense, and horror. The first broadcast of NBC’s “Inner Sanctum” came on January 7th, 1941, and some 500 episodes would be produced before it finally went off the air in October of 1952. As that phenomenal longevity implies, “Inner Sanctum” was among the most popular radio programs of its type, and further media colonization was almost inevitable. Universal Studios were the first to license film rights to the Inner Sanctum name, using it to give brand identity to a succession of six cheap, hour-long thrillers made between 1943 and 1945. Universal’s Inner Sanctum movies were promoted as mysteries, but that was somewhat misleading— Fritz Leiber’s Conjure Wife, the basis for Weird Woman, was hardly a whodunit, after all. That genre tag was, however, a somewhat better fit in the case of Calling Dr. Death, the first film in the series. It may have little or no concern for the actual process of crime-solving, but the identity of a murderer is at least the movie’s central issue.

We start off in the offices of neurologist Dr. Mark Steele (Lon Chaney Jr.), where he is placing a teenage girl under hypnosis in an effort to treat her psychosomatic muteness. We needn’t concern ourselves with her case, however, for this scene is of a purely instrumental nature. First, it introduces the premise that hypnosis can be used to access repressed memories, closely guarded secrets, and truths too painful for the conscious mind to face. Secondly, it establishes that screenwriter Edward Dein can’t tell the difference between a neurologist and a psychiatrist. No, what we need to pay attention to is Steele’s voiceover narration (delivered in a hilarious raspy whisper), in which he fumes over the imbalance between his professional and romantic lives: “The results are beyond imagination! To penetrate man’s mind intrigues me more and more… But my personal life is a failure— after two years of marriage to Maria, it’s no go… I hate her!” Maria (Ramsay Ames, from The Mummy’s Ghost and Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves) was supposed to be Steele’s trophy wife, but instead she has very efficiently made a trophy out of him while he wasn’t looking. She gets the prestige and the disposable income that goes with being married to a successful doctor, while he gets to come home to an empty house every night and wonder whose cock is in his wife’s mouth this time.

For the record, the current guy’s name is Robert Duvall (David Bruce, from The Mad Ghoul and The Smiling Ghost), and he’s an architect every bit as successful in his field as Steele is at hypnotizing teenagers when he ought to be, like, studying Parkinson’s disease or something. Steele himself knows nothing about that, of course. In fact, he’s never seen his rival at all before tonight, when he catches Duvall dropping Maria off at home shortly after 3:00 AM. Her arrival in the apartment touches off a fight that culminates in Mark telling Maria to her face that he’s thinking about killing her, and Maria countering that he hasn’t got the guts.

That was Thursday. Steele closes down the office early on Friday afternoon, and somehow manages to be surprised to find his wife out of the apartment when he comes home. Bryant the butler (Holmes Herbert, from Mark of the Vampire and The Undying Monster) reluctantly informs Steele that Maria mentioned something to him about going away for the weekend, and the doctor kind of snaps. He climbs into his car, heads out toward the country, and drives and drives and drives. The next thing Steele knows, it’s Monday morning, and his assistant, Stella Madden (Patricia Morrison, from Queen of the Amazons), is waking him up at his desk in the office. He doesn’t remember a damned thing about the weekend, a point which becomes vastly more alarming when a pair of detectives show up bearing the news that Maria is dead. Her body was discovered at the Steeles’ vacation lodge, and foul play is very definitely the favored hypothesis. People don’t often accidentally beat themselves to death with fireplace pokers and burn their faces off with acid, you know. Stella quickly impresses upon Mark the importance of not saying anything to the cops about his weekend blackout, and volunteers herself as his alibi. It’s an ass-covering maneuver for her, too, since the mutual affection between her and her boss is at least as obvious as Steele’s loathing for Maria. It wouldn’t take a very imaginative detective to look at the circumstances and postulate that the cuckolded husband murdered his wife with the assistance of the woman most likely to take her place, and Inspector Gregg (J. Carrol Naish, of The Monster Maker and Strange Confession), the lead cop on the case, has nothing wrong with his imagination. Neither, for that matter, does Steele, whose greatest worry is not merely that he will be charged with Maria’s murder, but that he might actually have committed it during his 60-some missing hours.

This is where things take a pronounced turn for the stupid. Despite the fact that Gregg considers Steele his number-one suspect, the police arrest Duvall— whom they shouldn’t even know about, so far as I can tell— and begin railroading him toward death row just as fast as they can. Then Duvall and his wife (Fay Helm, of Captive Wild Woman and The Wolf Man) each beseech Steele to help them clear the adulterer’s name. Yeah. ‘Cause whenever I’m in trouble with the law, the neighborhood neurologist is the first person I turn to in order to get me out of it— especially when he knows full well that I’ve been boning his wife! Also, just like Duvall, I invariably make sure to tell him that I began the affair in the hope of gaining access to his money, so that I can pay off my piles and piles of gambling debts. That sort of thing really builds trust and empathy, I find. Of course, that’s not nearly as dumb as Mrs. Duvall’s part in the program. She, too, knows that her husband has been having an affair, and what’s more, she knows that the son of a bitch has been fixing to leave her ever since she was paralyzed in an accident a year or so ago! Most women I know, in her position, would be happy to let the bastard fry. Anyway, Steele agrees to give the Duvalls whatever aid he can (even though the only thing he could plausibly do for them would be to admit that he killed Maria himself, and he isn’t even sure if that’s true), but his “help” seems to consist mainly of reading the newspaper and whispering in voiceover. That sort of thing naturally avails Robert nothing, and he is swiftly convicted and sentenced to die.

Now in any halfway-reasonable movie on this premise, that would be the end of the authorities’ involvement in the plot, and the rest of the film would concern itself with Steele cracking up over the prospect that he might have permitted an innocent man to die in his stead. Calling Dr. Death is not a halfway-reasonable movie, however, and so while Duvall watches the clock tick from his short-term prison cell, Inspector Gregg keeps hanging around, harassing Steele and Stella over their role in a case that should never have gone anywhere near trial unless he considered it closed. As you’d probably surmise from the opening scene with the hysterical mute, Steele eventually resorts to hypnosis in order to pin down the events of his lost weekend, putting himself under and having Stella record the story he relates from his trance. Even that does not suffice to bring this movie to an end, though, for Calling Dr. Death still has one last, giganimous cheat up its sleeve…

It’s that last, giganimous cheat that makes it impossible to take Calling Dr. Death seriously as a mystery, relegating it instead to the status of a brain-dead horror/suspense flick. As would so often happen in the years to come, the big, climactic reveal makes next to no sense, and pins the murders on somebody whose motivation for committing them requires a last-minute flashback to justify it. That technique didn’t work for Torso or My Bloody Valentine, and it doesn’t work here, either. Another thing that doesn’t work is the attempt to portray the film’s main conflict as a battle of wits and wills between Dr. Steele and Inspector Gregg. As played by Lon Chaney Jr. and J. Carrol Naish, those two characters haven’t enough of either quality between them to stage a proper battle— a spat, maybe, or possibly a tiff, but certainly not a battle. The movie’s reliance upon hypnotically induced flashbacks and voiceover monologues to perform practically every expository function gets old before we’ve even left Dr. Steele’s office that first time, but continues all the way to the ridiculous, dishonest conclusion. And as I hope I’ve made clear already, the overall plot of the film is a tangle of complete non-sequiturs, predicated upon possibly the most bizarre misunderstanding of the American legal system that I’ve ever seen. It’s more than enough to outweigh the positive impact of a few interesting proto-noir touches, and only the one-hour running time prevents Calling Dr. Death from becoming really offensive in its badness.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact