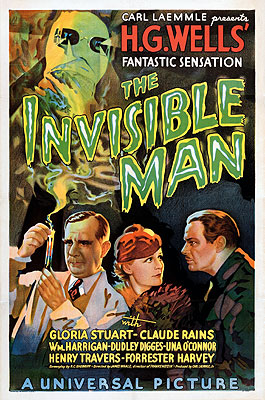

The Invisible Man (1933) ***½

The Invisible Man (1933) ***½

James Whale’s output as a horror director was about as hit-or-miss as it is possible to be. He made four films in the genre, all of them much loved by professional critics, but for my money, only two of them are in any way worthwhile. The man’s problem, I think, was that he didn’t really want to make horror movies at all— he wanted to make broad, campy farces. Frankenstein was the only really serious horror flick Whale ever made; with the rest, he indulged his comedic impulses to a greater or lesser extent. Twice, the results were disastrous. (I know most people love ‘em, but Bride of Frankenstein and The Old Dark House really made me mad.) With The Invisible Man, however, Whale was able to reign himself in enough to pull the trick off. It’s got its moments of overdone foolishness, but they’re few and far enough between that they don’t get in the way of what really is one of the best horror films of the 1930’s.

One inhospitable, snowy night, a lone man in an overcoat and dark glasses, with his face completely swaddled in bandages, arrives on foot at an inn in a small English village. The man arranges to rent a room from the innkeeper’s wife (Una O’Connor, in a more restrained version of the “screaming is funny, right?” performance she would later give in Bride of Frankenstein) and orders dinner brought up to him. As the woman leaves him alone in his room, he adds that he does not wish to be disturbed by anyone, for any reason. This mysterious traveler is a scientist by the name of Jack Griffin (Claude Rains, from The Wolf Man and The Phantom of the Opera, in his first performance for the American screen), and he has very good reason for not wanting company. As is revealed when he unwraps the bandages from around his head, Jack Griffin is completely invisible!

Why, exactly, Griffin made himself invisible in the first place is something the movie never really addresses. It may simply be, as is so often the case when mad science is involved, that he realized one day that it might be possible, and set about immediately to make it happen. In any event, Griffin made at least one major miscalculation in designing his experiment— he made himself invisible before he had figured out a way to make himself visible again! Obviously foresight is not the man’s strong suit. His invisibility is actually the whole reason why Griffin has come to this Godforsaken hamlet. He figures that, so far away from the pressures of his regular life— his job, his girlfriend, the world— he will be able to devote his undivided attention to the problem of restoring his opacity. But Griffin seems not to have taken into account the propensity of small-town people to be nosy, suspicious gossips, and it turns out that he has even less peace at the inn than he would have had he stayed in whatever city it is that he calls home. With all the interruptions, it’s no wonder that Griffin’s money runs out before he’s found his antidote, and when the innkeeper and his wife attempt to throw him out of his rented room, the harried scientist takes it rather badly. Not only does he refuse to leave the inn, the throws the innkeeper out of his room— literally— and causes thereby a scene that brings the police straight to him. Faced with this situation, Griffin goes a little nuts. He ostentatiously unwraps his invisible head, and while the cops, the innkeeper, and the rest of the rubes from the inn gape in awe and terror, strips down completely and gives his would-be captors the slip. The townspeople make some attempt to apprehend him, but they really haven’t got a chance— I mean, come on... how the fuck are they going to catch a guy they can’t even see?

Meanwhile, wherever Griffin came from, his friends and coworkers are starting to worry about him. Seems the scientist went to great lengths to conceal the nature of his work from the people close to him, and he naturally didn’t tell any of them where he was going when he ran off to the country to experiment in peace. His girlfriend, Flora (The Old Dark House’s Gloria Stuart), is especially frantic over Griffin’s disappearance, but not so frantic that she doesn’t notice the way Griffin’s closest colleague, Dr. Kemp (William Harrigan), is trying to use the man’s absence as an excuse to win her away from him. That kind of opportunistic scumbaggery clearly marks Kemp out for a rough time later on, just you watch. Meanwhile, Dr. Cranley (Henry Travers)— Flora’s father and Griffin’s boss— has discovered a clue as to what Griffin may have been up to. When Kemp shows him the empty cabinet in which Griffin used to keep the materials for his hush-hush project, Cranley spots a folded up piece of paper on one of the shelves. It proves to be a list of chemicals, including a dangerous bleaching agent called monocaine. According to Cranley, monocaine isn’t just the world’s most powerful lightener. If administered to an animal (or presumably a human being), it will gradually produce madness and extraordinarily heightened aggressiveness. And when Cranley and Kemp hear reports on the radio that a small country village has been seized by a wave of mass hysteria involving widespread claims that an invisible maniac is on the loose, the two scientists put two and two together and are floored by what they add up to in this case.

But the shock of that realization is nothing compared to what confronts Kemp when he gets home. You guessed it— Griffin is there waiting for him, and he has a job for his old friend. It isn’t help finding a cure that Griffin wants, though. The monocaine in the invisibility formula seems to have already done quite a number on Griffin’s brain, because what the invisible man wants is a visible accomplice to assist him on a reign of terror with the ultimate aim of world domination! Kemp figures that he can pretend to go along with Griffin, and then call in Cranley and Flora at the first opportunity in the hope of talking some sense into the transparent nutcase. Then the three scientists could put their heads together and come up with an antidote. Kemp is in fact able to place a call to the Cranleys, but when they arrive at Kemp’s place, they have a police escort with them, and Griffin, enraged, runs off again.

Just days later, it becomes evident that Griffin didn’t really need Kemp after all; he’s perfectly capable of engineering a reign of terror all by himself. Griffin steals, kills, causes train wrecks— the works. His activities may not be too clearly related to his expressed goal of ruling the world, but he does manage to paralyze the countryside with fear. This reign of terror will inevitably be a short one, however, for Griffin, invisible or not, is but one man, and he has the entirety of England’s police forces on the hunt for him. Not only that, such frequent English weather conditions as fog, rain, or snow will deprive him of even his one advantage. He’ll leave footprints in the snow, his body will disturb fog or mist as he passes through, and rain will coat his invisible body with rivulets of visible water. As time goes on, even Griffin seems to see the hopelessness of his original plan, but he can still use his invisibility to settle the score with Kemp, who’s going to need every single last one of those cops who’ve been escorting him everywhere if he’s going to get out of this movie in one piece.

The Invisible Man was a good choice for Rains, assuming he actually wanted stateside stardom. Despite the fact that he appears on camera only for a few moments at the movie’s end as anything other than a mass of floating garments, Rains dominates the film completely. His voice-acting is fantastic— he’d have made a great radio performer— and he makes fully believable Griffin’s gradual transformation from curmudgeonly recluse who just wants to be left alone with his work to homicidal megalomaniac. You can hear his disgust for the rest of humanity escalating with each successive utterance. I really do think it’s Rains that kept the brakes on Whale’s clowning; even when Griffin’s just being mischievous, Rains’s voice sounds too hard-hearted and mean-spirited for real levity.

Before I take my leave of The Invisible Man, though, I think it necessary that I say a couple of words about special effects. Today, we pretty much take good effects work for granted. It rarely occurs to anyone these days to be amazed even by things that really are amazing, like, say, the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park. So it’s easy, here at the turn of the 21st century, not to notice how utterly incredible the effects in a movie like this one really are. This film repeatedly shows us such things as a partially dressed Griffin wandering around looking like nothing but a floating shirt. We see his footprints appear in the snow with no sign of what’s making them, we see him carrying objects around and manipulating them while he’s completely invisible, we even see him steal an extra’s bicycle and ride off on it. Nothing we haven’t seen before, of course, but when this movie first appeared nearly 70 years ago, this stuff was absolutely groundbreaking. And it was all done without the aid of the computers the makers of Hollow Man employed to do many of the same things only a tiny bit more convincingly. It’s when you sit down and really give some thought to what you might have to do to produce such images with the technology of the early 30’s that The Invisible Man really starts to look as impressive technically as it does from an artistic standpoint.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact