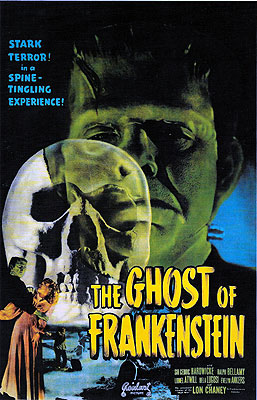

The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942) **½

The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942) **½

The Ghost of Frankenstein, the fourth entry in the Universal Frankenstein series, marks the franchise’s probably inevitable demotion to B-picture rank. Never again would the Frankenstein films aspire to the heights reached by Son of Frankenstein; from this point on, their sole purpose would be to cater to the less artistically rigorous tastes of the Saturday matinee crowd. Not only that, the series had lost its star along with its ambitions. Henceforth, the part of the monster would be played by whomever happened to be hanging around the studio that week. But even in spite of these setbacks in the casting and funding departments, The Ghost of Frankenstein manages to deliver a reasonably satisfying monster movie experience.

The movie opens with an unexpected reversal of the usual pattern. The previous three Frankenstein flicks had ended with a rampaging mob of angry, torch-wielding villagers. This film starts out with one. The mob in question is haranguing the burgomaster of the village of Frankenstein, demanding that the now-abandoned castle of town’s namesake family be demolished. Though no explicit mention of this is made, the townspeople are certainly within their rights to make such a demand, as Baron Wolf Frankenstein had bequeathed to them the title to his estate before leaving town for England at the end of Son of Frankenstein. The reason for the mob’s agitation is twofold. First, the old castle has come to symbolize the “curse” of the Frankenstein family, which has supposedly hung over the whole village ever since Heinrich Frankenstein first built his monster all those years ago. Secondly, the mad blacksmith Ygor (Bela Lugosi, reprising his Son of Frankenstein role), who had once befriended the monster and used it as a weapon against his enemies in the village, has taken up residence in the castle once again. (When the issue is raised that Ygor was shot to death at the end of the last movie, this one’s script forthrightly admits the impossibility of offering a satisfactory explanation by having one of the villagers pointedly remind his fellows that Ygor survived the gallows once— why not a hail of gunfire too?) Eventually, the burgomaster acquiesces, and allows the townspeople to raze the castle, after which the mob sets off at once, dynamite in hand, to do the job.

Ygor is less than pleased to see the crowd assembled before the castle walls when he mounts to the battlements to see what all the commotion is about. He tries for a while to drive the villagers away by pelting them with loose stones from his turret’s parapet, but the mob merely regroups at the foot of a stretch of wall beyond the reach of these crude missiles. The townspeople plant their explosive charges, and begin the work of demolition. Ygor runs as fast as he can for the comparative safety of the castle’s lower levels, and he thus survives the initial round of explosions. Picking his way through the rubble of the basement in search of a way to sneak past the mob, Ygor makes a remarkable discovery. One of the walls shattered by the blast abutted the sulfur pit into which the monster was thrown at the end of the last movie (note that the screenwriter has conveniently relocated the pit from its original position below Heinrich Frankenstein’s old lab, hidden away in an isolated corner of the Frankenstein estate). Not only the old stone wall, but the hardened sulfur as well was broken up by the villagers’ bombs, freeing the still-living monster (now played by Lon Chaney Jr.) from its rotten-egg-stinking tomb. Ygor is delighted to be reunited with his only friend, and he and the monster take advantage of the mob’s preoccupation with the task of planting another set of explosives to get clear of the castle grounds.

The monster is clearly a bit the worse for his years of entombment in the sulfur pit, but Ygor thinks he knows of a way to restore its strength. Old Baron Frankenstein, it seems, had two sons, and though Wolf has long ago fled for the safety of England, his younger brother Ludwig (Cedric Hardwicke, from The Ghoul and The Invisible Man Returns) is still around, practicing psychiatry in a town not so far from his ancestral home. Ygor and the monster set out at once to find Ludwig, whom Ygor believes to hold the secrets of his father’s and brother’s work. Any attempts at stealth and guile, however, come to naught from practically the moment the traveling miscreants arrive at their destination. While Ygor asks directions to Ludwig’s chateau, the monster wanders off and attempts to befriend a little girl who has lost her ball. A neighborhood boy callously kicked the toy up onto the roof of a nearby house, and the girl naturally has no way of getting it down from there. When the monster helpfully picks her up and carries her to the roof of said building, every adult in the square below jumps to conclusions, and comes running to the child’s “rescue.” This, of course, leads to the monster having to fight off yet another mob, killing two burghers in the process. Eventually, the police come and subdue the creature, hauling it off to jail in chains.

Enter Erik Ernst, the city prosecutor (Ralph Bellamy, from The Wolf Man and Rosemary’s Baby). A cursory examination convinces him that the monster is a mad, mute retard, and he goes to Ludwig Frankenstein to ask for a professional assessment of his prisoner’s personality. Ludwig, it turns out, happens also to be Erik’s future father-in-law— his daughter Elsa (Evelyn Ankers, of Son of Dracula and The Frozen Ghost) is engaged to marry the young lawyer. Frankenstein agrees to have a look at the prisoner as soon as he finishes with some paperwork regarding one of his patients, and sends Erik on his way. Then, mere moments later, the psychiatrist receives another visitor. Yup— it’s Ygor, alright. Ygor tells Frankenstein that he knows who he is (and more importantly, who his relatives were), and demands that he take the monster into his custody at the small clinic he runs in the basement of his chateau. Frankenstein, or so Ygor insists, will then do whatever is necessary to restore the creature to health, or Ygor will make sure that the reputation the Frankenstein family has back home follows Ludwig to his adopted city. It’s not the kind of thing Ludwig can really refuse; he’s made it a point for the last two decades to shield Elsa from the baleful influence of those skeletons in the family closet, and if cooperating with Ygor is the price he must pay to shield her further, then that is what Ludwig will do.

It’s a good thing the good doctor carries syringes full of tranquilizers in his bag wherever he goes, because he’s going to need them when he meets his father’s creation for the first time. The monster is chained up on the witness stand at the courthouse when Frankenstein arrives to examine it, and the moment it hears the doctor’s name, it goes berserk. After subduing the creature with the contents of one of those hypos, Frankenstein orders it committed to his care, and taken back to the hospital on his estate. But the monster is nothing but trouble, terrorizing Elsa (so much for keeping her in the dark about her family history...) and killing one of Frankenstein’s assistants. Eventually, Ludwig despairs of ever bringing it under control, and decides to destroy it instead, in the only way that it can be destroyed— piece by piece, as it was made in the first place. His partner and former mentor, Dr. Theodore Bohmer (Lionel Atwill, from The Night Monster and Mark of the Vampire), strenuously disapproves of this course of action, however. In Bohmer’s eyes, the monster is too close to human to be killed so cold-bloodedly. Fortunately, Frankenstein soon hits upon a better solution to the problem. After a little chat with the spirit of his dead father (a scene that seems to have been inserted into the screenplay for no reason other than to excuse the movie’s title— and by the way, notice that the actor portraying the titular ghost is not Colin Clive!), Ludwig realizes that the monster’s behavioral problems all stem from the abnormal, criminal brain given it by its creator. If the creature were given a new, normal brain, everything would be just fine! And by a fortuitous coincidence, the monster’s recent murder of Frankenstein’s assistant means that just such a brain is already lying around the hospital, just waiting to be used.

Ygor, however, doesn’t like this idea very much. Ideally, he’d like the monster to keep the brain it’s already got, but if Frankenstein is determined to give the thing a transplant, Ygor would rather his own brain be used. That way, he and his friend, the monster, could be together forever. Frankenstein refuses, of course— would you want to see what Ygor could do if his scheming, diabolical brain were installed in an immortal, superhumanly strong monster-body? No. I didn’t think so. But Ygor has an ace in the hole. He knows how unhappy Bohmer is to be working for his former protege, playing second fiddle to a man he taught. It doesn’t take a whole lot of ego-stroking to get Bohmer to substitute Ygor’s brain for the dead assistant’s when the time comes for him to help Frankenstein with the transplant, and so it comes to pass that Ludwig Frankenstein ends up creating a monster far worse than his father had. Looks like we’re going to need another torch-bearing mob over here...

Universal obviously weren’t asking a whole lot of The Ghost of Frankenstein. However, by downgrading the Frankenstein franchise to B-picture rank, they were doing no more than to bring it into line with what was increasingly becoming company policy. Although Universal had been the only Hollywood studio to turn a profit in 1931— largely because of the shocking amounts of money raked in by Dracula and Frankenstein— the firm was in disastrous fiscal shape only five years later. When the two Carl Laemmles sought a loan with which to finance James Whale’s Show Boat in 1936, they had been forced to put up the studio itself as collateral. In a story that would repeat itself again and again with other companies (Hammer’s To the Devil… a Daughter, American International’s The Amityville Horror, etc.), Show Boat’s blockbusting success came too late to do the Laemmles any good; as Whale fell behind on his shooting schedule, his bosses fell behind on their loan payments, and Universal fell into the hands of a consortium of investors led by John Cheever Cowdin. Cowdin clearly saw no shame downsized ambitions, and under his watch, Universal gradually remade itself into Hollywood’s greatest early exponent of the franchise model. The studio did still produce the occasional prestige film (what would have been marketed as a “jewel” or “super-jewel” back in Carl Laemmle Sr.’s day), but the main source of its profits were prolific series of cheaply made but easily marketable B-pictures. For all practical purposes, Universal spent the 40’s contentedly slumming on Poverty Row.

The potential for synergy between the new approach and Universal’s lingering fame as the home of Hollywood horror was obvious. After all, when you’ve got a hit movie about some thing that’s supposed to be dead in the first place, there’s little to stop you from bringing it back for a sequel. Early B-horror experiments like The Mummy’s Hand and The Wolf Man demonstrated the soundness of that premise, and by 1943, Universal had at least six and arguably as many as eight horror franchises running concurrently. Yet even after its re-positioning as cheap matinee fare, the Frankenstein series remained first among equals, and The Ghost of Frankenstein demonstrates that there could indeed be a bit of honor in that role. Unquestionably it’s a gigantic comedown from Son of Frankenstein, but it’s still a perfectly serviceable little movie. There are a few really good ideas on display in the admittedly rather muddled script, director Erle C. Kenton at least gets the job done, and the performances from the cast are solid all around— even Lugosi’s, which is nearly up to the standard set by his previous portrayal of Ygor. Though the approach taken by the studio here is inherently limiting, The Ghost of Frankenstein can, if nothing else, be said to make the most of what those limits allowed.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact