The Ghoul (1933/1934) ***

The Ghoul (1933/1934) ***

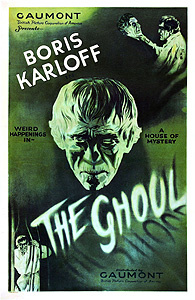

As I’ve mentioned before, there were very few Hollywood-style horror movies made in Great Britain during the 1930’s and 1940’s— the British Board of Film Censors took a look at the stuff that was filtering in from the States in those days, and essentially told the studios in their own country, “Don’t you fucking dare.” A few studios did dare, however, and among them was a little outfit called Gaumont, whose producers managed to convince Boris Karloff to devote part of his first extended trip home since he became a big-shit movie star to acting in a scrappy and rough-edged horror movie on the Universal model. Indeed, it might not be stretching the point too far to say that The Ghoul represented a forthright attempt to give British audiences a homegrown answer to both Frankenstein and The Mummy. And while the badly mangled prints that have been in circulation for most of the years since its initial release have obscured this, The Ghoul really was one of the better horror films of its era, regardless of nationality.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned from watching old British movies, it’s that white people become even less convincing as Middle Easterners when you slather them with swarthifying makeup that would probably have shown up bright orange on color film. We get to see a sterling example of this principle in action when Arab antique dealer Aga Ben Dragore (the conspicuously non-Arabian Harold Huth) receives an extremely hostile visit from a man named Mahmoud (the even more conspicuously non-Arabian D. A. Clarke-Smith) at his London flat. Mahmoud has come about something called the “Eternal Light,” which he claims Ben Dragore stole from an ancient tomb in their mutual homeland of Egypt, but the antique dealer swears he no longer has it. Rather, he sold the thing some time ago to an Englishman named Professor Morlant (Boris Karloff), whom he describes as a believer. (As usual, the makers of The Ghoul have failed to notice that the Egyptians converted to Islam a good 1200 years before their time, and to Christianity about 300 years before that!) Recognizing that Morlant will therefore be loath to resell the mysterious ancient treasure, Mahmoud intimidates Ben Dragore into assisting him in a scheme to recover it, so that it may be returned to its original resting place by the banks of the Nile.

Chances are, you’ve already figured out that Professor Morlant is a fucking weirdo. For one thing, there’s that business about him apparently adhering to the long-extinct religion of ancient Egypt, and for another, he’s played by Boris Karloff, and that’s usually enough all by itself. But of greater importance still, he’s a fucking weirdo on death’s doorstep. Morlant has suffered for years from some chronic ailment, and it’s quite plain that he isn’t going to be sticking around for more than another couple of hours by the time we meet him. Consequently, his creepy, torch-lit, old mansion is practically crawling with hangers-on of one sort or another. There’s a doctor, of course, along with Morlant’s long-suffering Irish butler, Laing (Ernest Thesiger, from Bride of Frankenstein and The Murder Party), and his blatantly unscrupulous lawyer, Broughton (Cedric Hardwicke, of The Invisible Man Returns and the RKO version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame). There’s also a parson named Nigel Hartley (Ralph Richardson, who would turn up a lifetime later in Frankenstein: The True Story and Dragonslayer), who is hell-bent on giving Morlant his last rites, even though the professor is a committed pagan who wants nothing whatsoever to do with Hartley or his God. Morlant, smart guy that he is, trusts none of these people except for Laing, whom he regards as being too simpleminded to fuck him over successfully. Therefore it is to Laing alone that Morlant conveys his final instructions for his burial. Morlant is to be interred Egyptian-style, in the tomb he had constructed on his estate, and it is absolutely essential that he be buried clutching the ancient jewel on which he recently spent the better part of his fortune. To that end, he has Laing wrap up his left hand in bandages, so that none of the human jackals Morlant has prowling his house at the moment will see the gem in his palm. The reason for all this rigmarole is that Morlant believes the jewel— that Eternal Light Mahmoud and Ben Dragore were talking about earlier— will open for him the door to the afterlife of pagan Egypt, securing his entry into an eternal paradise that doesn’t work out essentially to being stuck in church forever. Hey, it sounds like a fine idea to me. There are two obstacles to the smooth execution of Morlant’s plan, however. First of all, everyone he knows disapproves strenuously of his religious convictions, and after he’s dead, there will surely be pressure from all sides to give him a decent Christian burial instead. Second, Laing disapproves even more strenuously of sealing the Eternal Light up in a tomb. After all, a dead man has little use for jewelry (assuming you don’t buy into Morlant’s beliefs about the afterlife), and the professor dropped fully £75,000 on that particular bauble— the way Laing sees it, burying the Eternal Light means depriving Morlant’s heirs of the vast bulk of their inheritance. Unsurprisingly, Laing contrives to remove the gem from Morlant’s hand sometime between his death and the funeral the following night, even despite the old man’s warning that he will return from the grave to punish anyone who interferes with his journey to the next world.

As for those heirs Laing has defied his master in order to protect, they consist of a pair of cousins from feuding sides of the family. Ralph Morlant (Anthony Bushell, from “Quatermass and the Pit”) and Betty Harlon (Dorothy Hyson) have been raised since early childhood to despise each other, but neither one of them would be able to explain if asked just what lies at the root of their mutual animosity. Circumstances are about to dictate that they put aside their differences, though, because even the most guileless and trusting of observers could see that Broughton is out to swindle them both. Ralph figures that out after only a few minutes in the lawyer’s company, and he rushes over to his cousin’s place in an effort to get to her before Broughton can. Ralph finds Betty in a receptive state of mind, because he arrives immediately after somebody (Betty has never seen Laing before) had handed her a note warning her of a conspiracy against her, which somebody else (she hasn’t met Broughton yet, either) immediately robbed her of before vanishing into the dense London fog. The two cousins embark for the professor’s mansion at once, grudgingly bringing along Betty’s roommate, Kaney (The Ghost Train’s Kathleen Harrison), who insists upon coming for no reason that I can fathom.

Ralph and Betty figured they’d be arriving at an empty house, but that’s not quite how things turn out. To begin with, Laing still lives in the mansion’s servants’ quarters, so that he can stand watch over the hidden Eternal Light. Secondly, Broughton has been spending most of his free time of late out at the house in a dogged search for whatever fabulously valuable object might account for that £75,000 outlay he found in Morlant’s financial records. Then more evidently self-interested visitors arrive, in the form of Parson Hartley and the two scheming Egyptians. What all this really means is that Morlant will have plenty of ass-kicking to do when, true to his word, he rises from his coffin under the light of the full moon, and comes to collect his property.

Those who are wise in the ways of early British horror films will not be surprised to learn that The Ghoul backtracks in the end to provide a rational explanation for its seemingly supernatural horrors, but to the great credit of screenwriters Roland Pertwee and John Hastings Turner, it does so in a way that does not undercut anything we’ve seen up to that point. To be sure, the explain-it-all-away ending is sort of irritating, but at least it doesn’t cheat. The squeamishness of the Board of Film Censors is also reflected in the almost absurdly high survival rate among the characters after Morlant’s rampage begins, which makes such things as the sight of Morlant carving the sign of the ankh into his own chest or the extremely kinky conversation that unfolds in the pantry between Aga Ben Dragore and Kaney (whose main function here is to provide comic relief by throwing herself at any man who looks her way twice) all the more shocking when they come up. Meanwhile, The Ghoul is probably the most intensely atmospheric British horror movie I’ve seen from the early days— for once, we have a lightless, moldering mansion that really is creepy enough to carry a movie through the long stretch until the supposedly dead man climbs out of his coffin— and director T. Hayes Hunter does a commendable job of using that atmosphere to disguise the movie’s slow pace and thinly-stretched plot. Karloff himself unfortunately doesn’t get to do much, but Cedric Hardwicke more than covers for him, and it’s good to see Ernest Thesiger in a horror movie doing something other than his standard Bitchy Old Fairy routine. On the other hand, with the sole exception of Ralph Richardson (who doesn’t get enough screen time to make much of an impression one way or the other), every cast member under the age of 40 puts in an absolutely putrid performance, with Dorothy Hyson and Kathleen Harrison evidently vying with each other for the Most In Need of a Good Throttling crown. The Ghoul is too good otherwise for the younger actors to wreck it completely, but lord knows it isn’t for lack of trying on their parts.

A concluding word of caution: There are two versions of The Ghoul available, and they may as well not be the same movie. Either one of the DVD editions (the MGM version or the dollar DVD marketed by Movie Classics) will do you right, but most VHS copies in circulation were taken from a horrendously decayed and mutilated Czechoslovakian print which was believed to be the only one in existence until relatively recently. By all accounts, the old Czech print is nearly incomprehensible, so dark and blurry that it would be hard to follow the action even if more than a reel’s worth of footage (including several important plot points) hadn’t been missing from it. If you’ve already seen it on videotape, you really ought to give The Ghoul another chance on DVD; if you haven’t yet seen it at all, you’d be doing yourself a disservice by settling for one of the older editions.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact