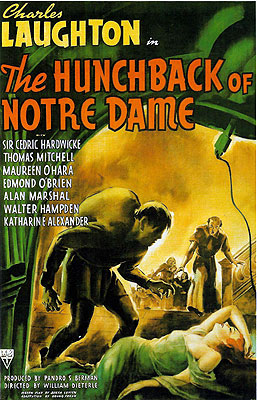

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939) *˝

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939) *˝

You know, for the life of me I’ve never been able to figure out why this movie has historically been reckoned a horror flick. Sure, Quasimodo is awfully ugly, and sure, Esmeralda does get tortured just a little bit, but come now. Really, this is just a big, stupid, platitudinous melodrama— a B-picture on an A-budget, with grand sets, some decent makeup effects, and one fine performance combining to buy it a reputation far in excess of anything it actually deserves.

The only thing really horrifying about The Hunchback of Notre Dame is its two solid hours of relentless, ham-fisted, self-congratulatory pontification. Indeed, the preaching begins before we’ve even met a single character, when a title card so verbose that the camera needs to scroll down it for nearly a minute tells us that France in the 15th century was a bloody battleground between the forces of benign progress and benighted ignorance. Just great. Then, just to make sure we’ve got the point, the filmmakers take us to the headquarters of Paris’s first printing press, which is just then being toured by King Louis XI (Harry Davenport) and Count Claude Frollo (Cedric Hardwicke, from The Ghost of Frankenstein and The Invisible Man Returns), chief justice of the highest court in France. Frollo, predictably, regards the printing press as a blasphemous abomination that will surely bring ruin to Western civilization. King Louis, on the other hand, quite likes the invention, especially the the part about how if it catches on, it promises to help make the commoners of France well enough educated to want to overthrow his descendants. Is it possible that anyone could have been sufficiently naive to believe this shit— even in 1939?!?!

Meanwhile, outside the gates of the city wall, a caravan of Gypsies is being refused entry into Paris, on the grounds that all Gypsies are thieving, degenerate heathens who ought to be exterminated by fire and sword. (I wonder if this part of the movie was in any way inspired by what was going on in Europe when it was made...) One of these Gypsies, a lovely girl named Esmeralda (Sinbad the Sailor’s Maureen O’Hara), is sly enough to sneak by the guards at the gatehouse while the headman of her tribe argues with their captain. She eludes capture by vanishing into the crowds, then later turns up in the main square, just in time to take part in the Festival of Fools. Apparently, this is some big, city-wide celebration of drunkenness, pick-pocketing, and generalized hooliganry, and is the highpoint of the year for the Parisian Lumpenproletariat. Even the king and his court get in on the fun! This year, a failing poet named Gringoire (Edmond O’Brien, later of Fantastic Voyage) is attempting to stage a play of his own composition at the festival— some grand philosophical foolishness about the equality of all men in the face of mortality— and it is not going over very well. All the assembled paupers care about is the crowning of the King of the Fools, a contest in which Paris’s poor match their ugliness against each other, until the most grotesque man of all is declared king. While all that’s going on, elsewhere in the square, Esmeralda dances to Gypsy folk songs. The two tableaux are united when the girl notices someone watching her from underneath a set of bleachers. That somebody is Quasimodo (Charles Laughton, from The Strange Door and Island of Lost Souls), the hideously deformed bell-ringer at Notre Dame cathedral, and when the crowd gets a look at him, he is unanimously awarded the crown as King of the Fools. (No mean feat, considering that one of his competitors is played by Rondo Hatton!) The fun is cut short, though, when Frollo (in attendance with the real king) sees what’s going on and takes exception to all the fun the hunchback is having. He puts a stop to the whole undignified business, and leads Quasimodo back to the cathedral.

Frollo’s brother, it turns out, is the Archbishop John (Walter Hampden), top-ranking clergyman at Notre Dame. Quasimodo has lived at the church in John’s care ever since Frollo “adopted” him as a child. The hunchback is devoted to Frollo, and the justice is the only person he’ll really listen to. (Although technically, Quasimodo can’t listen to anyone— ringing the bells all his life has left him deaf as a post.) And here again, we have our faces rubbed in the movie’s message, as John, despite his status as a churchman, suggests that Frollo is being too stern in his condemnation of the few simple pleasures the half-wit hunchback is able to take from life. Not only that, the movie soon comes down even more stridently in favor of nakedly anachronistic notions of tolerance, when soldiers from the town square chase Esmeralda (who naturally doesn’t have her green card on her) to the cathedral, where she is forced to seek sanctuary. The soldiers don’t think sanctuary applies to Gypsies, and neither does Frollo, but the cathedral clergy take a rather more enlightened view of the issue. The priests also seem not to agree with Frollo’s conviction that Gypsies shouldn’t be allowed to pray for the intercession of the Virgin Mary— or indeed to pray for anything within the hallowed confines of Notre Dame cathedral— though that disagreement doesn’t stop the count from telling Esmeralda what he thinks to her face. Do you get the point yet? No, I’m not sure I do either— maybe the filmmakers can bludgeon us with it just a few more times.

Next we go to set up the inevitable love triangle, or in this case, the love pentagon. Frollo, Gringoire, and a guardsman by the name of Phoebus (The House on Haunted Hill’s Alan Marshall) all took notice of Esmeralda while she danced at the festival. Gringoire and Phoebus simply like the Gypsy girl, but Frollo gradually develops a pathological obsession with her, stemming from her unwelcome stimulation of his long-suppressed libido. When Frollo tries to use Quasimodo to effect his possession of Esmeralda, Gringoire sees the hunchback chasing her down the street, and calls on Phoebus to rescue her. Further complications result in Esmeralda “marrying” Gringoire to save him from being hanged by Clopin (Thomas Mitchell, of Flesh and Fantasy), the “King of the Beggars.” Gringoire is thrilled with this turn of events, but not only can a marriage officiated by Paris’s top bum scarcely be considered binding, Esmeralda doesn’t really return his love— she just wanted to save him from his peril. Naturally the one she really wants is Phoebus, who saved her from Quasimodo.

Which brings us to the hunchback’s legal problems, and thereby to the fifth corner of that love pentagon. Quasimodo is sentenced to 50 lashes and an hour in the pillory for his attack on Esmeralda— nevermind that the whole thing was Chief Justice Frollo’s idea in the first place! After seeing the lictor beat the shit out of the poor freak, followed up by more abuse from the jeering crowd, Esmeralda takes pity on the hunchback, and mounts the pillory to give him a drink of water. It’s probably the first time in his life that anyone has ever done anything really nice for Quasimodo, and it’s undoubtedly the first time he’s experienced an act of kindness from a pretty girl. You know where this is going.

But Frollo has decided that Esmeralda has a few too many suitors for his liking, and he sets about narrowing down the playing field. At a show put on by the Gypsies at their camp outside Paris, Frollo murders Phoebus, and then frames Esmeralda for the crime. I guess the girl made it clear to him that she wasn’t interested, leading the count to invoke the ever-popular “if I can’t have you, no one will” principle. And wouldn’t you know it, Frollo himself gets to preside over her trial, at which the girl will stand accused not just of murder, but of witchcraft as well. The procurator of the court (George Zucco, from The Mummy’s Tomb and The Flying Serpent), inevitably, will be seeking the death penalty. But even with the deck stacked so strongly in his favor, Frollo isn’t taking any chances. He sends a contingent of soldiers to that printing press we saw in the first scene to destroy the machine, thereby preventing Gringoire from publishing the inflammatory pamphlet he has written in response to Frollo’s machinations. But curiously enough, amid all these preparations, Frollo makes the stupid mistake of confessing his crime to his brother. You just know this is going to get the count into trouble later.

Esmeralda’s trial is a resounding success, at least as far as Frollo is concerned. After hearing the testimony of several witnesses (including the goat accused of being Esmeralda’s familiar!), the court is able to extract a confession under torture. Even a last-minute intervention by the king himself fails to save the Gypsy girl, as the trial by ordeal ordered by the king judges against her. But Esmeralda is rescued from the very gallows by Quasimodo, who swings down on a rope, clobbers the hangman, and carries the girl back to his bell tower in the cathedral. Subsequent attempts by various parties to wrest her away from the hunchback result in much bloodshed and destruction before Archibishop John is able to shame Frollo into confessing to the king, winning a pardon for Esmeralda and a newly liberalized royal Gypsy policy for her people. And they all lived happily ever after...

Except that in the Victor Hugo novel upon which this movie is based, they all most certainly did not. Even more than all the sanctimonious preaching and politically correct anachronisms (some 50 years before political correctness in its modern form had even been invented!), it’s this cop-out happy ending that pisses me off about The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Hugo’s version of the story is a fucking tragedy! Turning it into a movie about the triumph of tolerance and enlightenment over bigotry and ignorance is like filming a version of Romeo and Juliet in which the feuding families kiss and make up at the end, so that the star-crossed lovers can get married, have two smiling blonde children, and buy a station wagon and a house in Levittown! No matter how lavish the production values, no matter how sensitive Charles Laughton’s performance (and he is really good), no matter how perennially warm its reception by posterity, The Hunchback of Notre Dame is reduced to nothing less than a complete travesty by the ending alone. And with that ending coming at the far end of 120 minutes of smug self-righteousness, my opinion of this film falls low indeed.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact