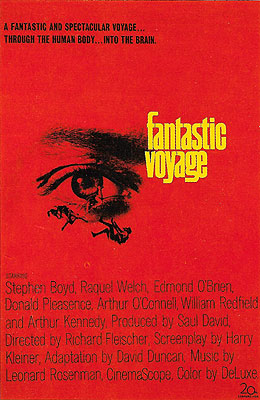

Fantastic Voyage (1966) **

Fantastic Voyage (1966) **

There has been a lot of talk during the past decade, and during the past couple of years especially, about the way in which today’s unprecedented special effects technology has been sucking all of the life out of the movies. I’m sure if you thought about it for even a few minutes, you could name quite a few recent films that seem to exist for no reason other than to showcase the wizardry of their effects teams. The thing is, though, that this is not, no matter what anyone may try to tell you, a recent development. Anybody else remember Star Trek: The Motion[less] Picture? That celluloid sleeping pill came out way back in 1979. And more to the point, Fantastic Voyage first dragged its weary carcass onto the screen 13 years before that!

You hear that slow, rhythmic thudding sound? That would be the plot of this film struggling to advance itself. And yet, what we’ve got here is one of the most outrageous movie premises of a decade justly noted for movies premised on the outrageous. At some unspecified future date (but it can’t be that far in the future, because the secret government agency we’ll be meeting in a moment still uses ultra-swank 1964 Imperial Crowns as staff cars), a man named Grant (Stephen Boyd, in whose career Fantastic Voyage marks a nice midpoint between Ben Hur and Lady Dracula) has been summoned to the headquarters of a mysterious military unit called the CMDF-- Combined Miniature Deterrent Forces. As General Carter (Edmond O’Brien, from the 1939 version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame), the man in charge of the hidden, underground CMDF base to which Grant has been taken, explains, this top-secret outfit has the capability to shrink (by some means that the script wisely leaves unexplained) an entire division-- with its gear and support staff included-- such that it would fit inside a bottle cap. The reasons why the military would want such a capability take some pondering, but if you think about it long enough, I’m sure you’ll come up with a couple of applications. The only problems with the technology are, first, that “the Other Side” has it too, and second, that objects so shrunk will remain that way for only an hour before returning to normal size. Considering the fact that it takes a good ten or twelve hours to fly across the Atlantic, this inconvenient fact places some rather serious limits on the technology’s utility. So you can imagine the delight with which the Pentagon greeted the arrival in the U.S. of a scientist who has developed a way to keep shrunken objects small indefinitely. And I’m sure you can also imagine the dismay with which the Other Side greeted the same development.

Thus the Other Side did what Other Sides usually do in Cold-War-vintage movies, and sent agents to kill the scientist on his car ride to CMDF headquarters. They failed, but just barely. The man still lives, but the attack put him in a coma with some kind of hemorrhage-related brain damage, and because of the location of the injury, there is no way to repair it without completely disassembling the doctor’s head. Or, rather, there would be no way were it not for the CMDF’s shrinking machine. The plan is to shrink an experimental submersible called the Proteus down to the size of a single large cell, inject the sub into the scientist’s blood stream, and use it to transport Dr. Duval-- the nation’s foremost brain surgeon (Arthur Kennedy, whose career looked a lot like Stephen Boyd’s-- he went from The Glass Menagerie to this to a Laura Gemser flick called Taboo Island)-- right to the site of the hemorrhage to repair the damage with what might be the silliest looking laser rifle ever filmed. What all this has to do with Grant is simple, really. He’s an ex-G-man of some kind, and Duval’s loyalty is under suspicion for the sort of logically indefensible reasons that apparently made sense to people back in Cold-War days. Grant’s job is to go with Duval, his assistant Cora Peterson (One Million Years B.C.’s Raquel Welch, who looks nearly as good in a wet suit as she does in a fur bikini), and another doctor by the name of Michaels (Donald Pleasence, whom, if you’re reading this, you’re most likely to remember as Dr. Loomis in Halloween) to see to it that no funny stuff goes down when Duval gets a chance to turn his laser on the inside of his patient’s brain.

Finally, after what was easily the longest 45 minutes of my life-- during which we are introduced to the sub’s designer and pilot, Captain Bill Owens (William Redfield, from Conquest of Space), and have the plan explained to us in such detail that we could carry it out ourselves if called upon-- our intrepid voyagers are shrunk down and injected, bringing us to the main action of the movie. Considering what a short trip it is from the carotid artery to the brain, it’s amazing how much trouble Grant and company get themselves into. It all starts when they find themselves sucked through a fistula (a tear joining two blood vessels that ought not to be connected directly) from the carotid artery into the jugular vein. This, of course, means they’re now going the wrong way-- toward the heart, rather than the brain-- and more importantly, it means that the sub and everyone in it are now in mortal peril because the sub’s hull is too flimsy to withstand the pressure and turbulence that it will encounter inside the heart. Then, just when all seems lost, General Carter and the officer-surgeon overseeing the whole affair figure out that, while it should be possible to stop the patient’s heart for 60 seconds without killing him, it will take only 57 seconds for the submersible to transit the heart at maximum speed. So, against Dr. Michaels’s better judgement, Owens steers a course for the heart, setting in motion a course of events that ends in Fantastic Voyage’s first narrow escape for the Proteus and its crew.

The real problem with this movie’s script is that we’ve just seen the only trick it knows. For the next hour (the part of the film devoted to the titular voyage itself maddeningly seems to take place in real-time), we will be presented again and again with one of the characters-- Michaels, Duval, and Owens all get a shot, but the task usually falls to the former-- explaining the worst-case scenario for whatever organ the Proteus is entering, followed with numbing predictability by the emergence of the very situation about which we have just heard. Michaels warns of the potentially dire effects on the Proteus of any noise made in the operating room while the sub is inside the inner ear, and a nurse knocks a pair of scissors on the floor while she reaches to help a doctor stifle a sneeze. Owens worries aloud about what could happen if the reticular fibers of the lymphatic system clog the sub’s intake vents, and the team is forced to stop in the very next scene to scrape gloppy orange crap out of the vents of which he spoke. Michaels warns Grant about the dangers of attack from the patient’s antibodies should anyone damage the scientist’s tissues, and mere seconds later, Cora gets herself tangled up in the hair-cells of the man’s cochlea, tearing them and causing hordes of what look like strands of plastic kelp to swarm in to destroy her. In fact, the only time events don’t follow this pattern is the time when Michaels talks darkly of what would happen should the patient cough while the sub navigates between the lungs and the body wall.

And then there’s the espionage/sabotage angle. I’ve already mentioned that Grant’s entire purpose on the mission is to act as a watchdog for the suspect Dr. Duval. Over the course of the film, any number of suspicious things happen that are meant to make us wary of the surgeon. They’re meant to make us wary of Duval, but what they really do is make us wary of Michaels instead. To begin with, to the experienced viewer of bad movies, the Duval-as-double-agent story reeks to high heaven of red herrings from the moment the subject first comes up. Once you’ve seen more than a few of these movies, you start to learn their patterns, and the introduction of this idea comes at a point in the story that is almost invariably reserved for the planting of false expectations. But the character of Dr. Michaels himself is the real tipoff that Duval is on the up-and-up. It’s simple, really-- in Cold-War action films, the twitchy, nervous guy is always secretly working for the Other Side, as is anyone who could in any way be described as cowardly or unstable. Dr. Michaels is higher-strung than a goddamned Chihuahua, and he’s claustrophobic. No way he’s anything but a mole for the Other Side.

So now that I’ve completely ruined the “surprise” ending, I may as well tell you how it all turns out, huh? Would you believe a last-minute, race-against-time operation that is nearly foiled by Michaels’ treason, followed by a by-the-skin-of-their-teeth escape at the exact second at which the miniaturization begins to wear off? Of course you would. How could it be any other way?

But since the real point of Fantastic Voyage is its special effects, I suppose I ought to say a thing or two about them. By 1966 standards, they are indeed very impressive. However, they also point to the fatal flaw of all movies that forsake story in favor of special effects dazzle. To wit: no matter how breathtaking it may seem at the time, the relentless march of technology will always render the best effects work dated and hokey-looking within, at most, twenty years. And as the pace of technological advancement increases, this interval will only shorten, as indeed it already has. Willis O’Brien’s stop-motion animation in King Kong looked literally magical in 1933, but the seams were starting to show by the mid-1950’s. The Cantina Cafe scene in Star Wars blew just about everything that had come before it out of the water, but by the time Return of the Jedi was made, it was already well along the road to obsolescence. Ditto the then-amazing effects in the contemporary Star Trek: The Motion Picture. The difference between King Kong and Star Wars on the one hand and Star Trek: The Motion Picture on the other, which accounts for the former two films having stood the test of time while the latter is now an embarrassment even to the “Star Trek” faithful, is that the former have something going on underneath the surface gloss of their effects. Fantastic Voyage is about as empty of real drama, authentic excitement, or thoughtful scripting as a movie is capable of being. It remains pretty neat to look at, but even on that score, it is of mainly antiquarian interest. As it happens, I am an antiquarian, but I’m also honest enough with myself to realize that we’re a dying breed, and that a film like Fantastic Voyage will have little appeal for most people who were not yet alive to see it when it was originally released. Strip it of its nostalgia value, and all you have left is a vaguely highbrow Armageddon for a bygone era.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact