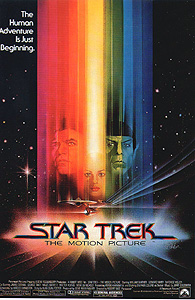

Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979) **

Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979) **

Looking back from the perspective of 2013, it’s amazing what a massive pop-culture phenomenon “Star Trek” wasn’t until a few years into the 1980’s. The show’s difficulties in finding an appreciative audience began all the way back in 1965, when CBS passed on it in favor of fucking “Lost in Space” and NBC rejected the first pilot episode— the best, smartest hour and a half of American television science fiction since Demon with a Glass Hand redeemed the weak second season of “The Outer Limits”— for being too cerebral. When the series was eventually green-lit on the strength of a new cast and a somewhat more face-punchy second pilot (incidentally, let’s take just a moment now to marvel over the fact that the “Star Trek” we know and love from the late 60’s was the dumbed-down version!), it faced indifferent ratings, budget cuts, the refusal of one in seven NBC affiliates to air it at all, and finally relegation to a deadly 10:00-on-Friday-night timeslot. “Star Trek” was never a failure exactly; it was a hit with critcs, and got more fan mail than any other NBC series except “The Monkees”— only some of which can be attributed to executive producer Gene Roddenberry’s back-channel boosterism. But it was never more than a cult success, either, at a time when the concept of cult success was not widely understood. Still, syndication kept up the show’s visibility throughout the 70’s, and the big brains at Paramount (which inherited the property when parent company Gulf+Western bought the Desilu production firm in 1968) spent the decade searching for profitable ways to exploit something that not many people liked, but that a few people loved with freakish, obsessive intensity.

First they tried the “kids love sci-fi, right?” angle, contracting out to Filmation for a half-hour “Star Trek” cartoon in 1973. It lasted 22 episodes, one half-season plus a severely truncated six-episode nub the following year. Then in 1976, they began development of a movie to be called Star Trek: Planet of the Titans, but it never quite came together. Next, in a remarkable foreshadowing of the mid-1990’s, somebody got the idea to use a revamped, big-budget “Trek” show to anchor the television network the studio was trying to launch. “Star Trek, Phase II” got surprisingly far into preproduction, with about half a season’s worth of scripts written, new sets built, and actors cast to play the three characters it took to replace Leonard Nimoy (who was at the height of his I Am Not Spock period at the time, and refused to have anything to do with the show). Only two things stopped it from happening. First, the financing for the Paramount network fell apart, leaving “Star Trek, Phase II” homeless unless NBC or somebody wanted to adopt it. And second, Star Wars came out about half an hour after Paramount’s “Trek”-related efforts shifted focus from Planet of the Titans to the new series. Suddenly, a movie looked like the better bet after all, and by 1978, “Star Trek, Phase II” gave way to Star Trek: The Motion Picture. Again, though, there was the whole “cult success” problem. If the original series had a hard time earning its keep at $193,000 per episode, how much harder was it going to be to recoup the $46 million that the studio would ultimately spend on the feature film? There was another big hurdle to be cleared, too. The previous huge sci-fi movie that Star Trek: The Motion Picture resembled most was not Star Wars or even Close Encounters of the Third Kind, but 2001: A Space Odyssey. For all the glitz and glamour of its special effects, it was a ponderous, cerebral, and achingly high-toned film, and because it was expanded from Alan Dean Foster’s script for the “Star Trek, Phase II” premiere, it didn’t have quite enough story to fill out its 136-minute running time. The result was familiar enough after fifteen years: not a flop, but also not half the success Paramount was looking for.

Somewhere in the depths of space, there’s… well, a thing. Hard to say what, really, beyond that it’s huge, incredibly powerful, and apparently purposeful. It’s surrounded by a cloud of energetic plasma roughly 7.6 billion miles in diameter, its energy output is comparable to a large blue star, and it’s moving like it (or somebody aboard it) knows where it’s going. Right now, the thing is in a sector claimed by the Klingon Empire, and a trio of that polity’s warships are ludicrously attempting to intimidate it into leaving their territory. The cloud-thing disintegrates all three vessels like the gnats they proportionately are. The battle, if you can call it that, is observed from afar by a long-range sensor and communications outpost belonging to the Earth-based United Federation of Planets, whose authorities become sensibly concerned. Concern turns to something more like panic when the Federation’s astronomers finish crunching the numbers to extrapolate the cloud-thing’s course. It’s headed straight for Earth, and at its present, nearly unbelievable speed, it should get there in about 50 hours.

The crew of outpost Epsilon 9 aren’t the only ones who caught wind of the Klingons’ curb-stomping. Psychic emanations from the mind at the center of the plasma cloud reach all the way to the Federation-affiliated planet Vulcan, where the logic-worshipping natives, attuned though they are to such input, imperiously refuse to give a shit. Well, all the natives but one, anyway. Among the planet’s inhabitants is a Vulcan-human hybrid by the name of Spock (Leonard Nimoy, from Invasion of the Body Snatchers and The Brain Eaters), who was once an officer in the Federation Starfleet. Spock, whose human ancestry has always made it difficult for him to practice the tenets of the Vulcan cult of pure logic, resigned his commission some years ago to join a monastery back home, in the hope that the adepts there could teach him some advanced techniques for boosting his self-control. He’s right in the middle of his graduation ceremony when the cloud-thing’s thoughts rush through his mind, and they so unsettle him that the space nuns in charge of his training declare him a hopeless case. Spock is too much his human mother’s son ever to master his emotions in the usual Vulcan manner. He’ll have to seek his answers elsewhere— and since the cloud-thing’s designs on Earth were what so rattled his composure, Spock figures the first elsewhere he should investigate is Mom’s home planet.

Meanwhile, in a spacedock orbiting Earth, the starship Enterprise is nearing the end of a lengthy refit and modernization. The big work of replacing the main engines, augmenting the weapons and defense systems, and enlarging the primary hull to accommodate additional personnel and equipment is done; now it’s just a matter of bringing everything fully online. The ship’s crew— including chief engineer Commander Montgomery Scott (James Doohan), communications officer Lieutenant Commander Uhura (Nichelle Nichols, from Truck Turner and The Supernaturals), helmsman Lieutenant Commander Sulu (George Takei, of Oblivion and Ninja Cheerleaders), and tactical officer Lieutenant Pavel Chekov (Walter Koenig, from Moontrap and Nightmare Honeymoon), all of whom were Spock’s shipmates aboard the Enterprise during a five-year mission of exploration in deep space— are right on schedule to complete the overhaul in 20 hours, but that schedule was drawn up before Starfleet Command heard the alarming news from Epsilon 9. Absurdly, the Enterprise is the only ship in position to intercept the cloud-thing before it reaches Earth, so the deadline for the remaining work is being pushed forward 40%. That’s not the only shakeup pending, either. The Enterprise’s new commanding officer, Captain Will Decker (The Henderson Monster’s Stephen Collins), was but recently promoted to the rank, and has never had a ship of his own before. The Chief of Starfleet Operations has convinced the rest of the Admiralty that a more experienced captain is needed for so crucial a mission, so Decker will have to accept a temporary demotion to executive officer. The man who’ll be doing Decker’s job— who will also be taking a temporary pay-cut— is none other than the Chief of Starfleet Operations himself, Rear Admiral James T. Kirk (William Shatner, from The Horror at 37,000 Feet and Incubus).

Not coincidentally, Kirk commanded the Enterprise before, on the aforementioned five-year mission. He’s also a notorious glory hound, so Decker is suspicious to say the least of the admiral’s motives for strong-arming the ship away from him. Nor are Decker’s the only toes Kirk steps on. The ship’s physician, Dr. Chapel (Majel Barrett, of Westworld and The Questor Tapes), was merely Nurse Chapel back in the day, and Kirk’s not going anywhere, if he can help it, without his old doctor, Leonard McCoy (DeForest Kelly, from Night of the Lepus). McCoy, like Spock, left Starfleet after returning to Earth, but Kirk isn’t going to let that stop him from getting the band back together. Technically, McCoy is in the reserves now, and reservists can be drafted. If there were time for a detour to Vulcan, you can be damn sure Kirk would soon be barging into that logic monastery, looking for Spock too. Actually, that would have been the best thing for Spock’s replacement as the Enterprise science officer, another Vulcan called Sonak (The Malibu Bikini Shop’s Jon Rashad Kamal), because the mad rush to get the ship out of spacedock results in Sonak getting Brundled by a matter transporter that nobody had checked yet to see if it actually worked before beaming him aboard. The same haste nearly gets everybody killed once the Enterprise is underway, when a malfunction in the warp engines creates a wormhole that traps the ship on a collision course with an asteroid. The one upside is that the delay necessary to fix that deadly fuck-up gives Spock time enough to reach Earth, board a warp shuttle, and catch up to the Enterprise to volunteer for his old job.

And now, at last, an astonishing 53 minutes into the film, the plot resumes its forward motion. The Enterprise intercepts the cloud-thing well clear of Earth, and efforts begin to determine what the hell is going on here. Attempts to communicate do nothing but to get the ship blasted with balls of hot plasma (luckily, the refurbished Enterprise is a lot tougher than those Klingon cruisers), until Spock thinks to try using the most primitive binary code in the computer’s library. After that, the mysterious entity permits the Enterprise to enter its cloud and approach the vessel at its core. Neither Kirk nor anyone among his crew mentions this, but the cloud ship is vaguely reminiscent of the automated alien planet-eating contraption they encountered once on their extended ramble about the galaxy. It’s both bilaterally and hexaradially symmetrical, roughly funnel-shaped, and bristling with all manner of unrecognizable sub-structures. And although it’s piddlingly tiny compared to its defensive nebula, it still dwarfs the thousand-foot Enterprise into insignificance. Certainly many dozen, and possibly several hundred miles in length, it must be as massive as a modest moon. As the Enterprise takes up a position ahead of it, a tractor beam of immense power seizes the Federation ship, and draws it into a hangar of sorts, which then closes with a colossal iris valve. Then the alien probes the captive vessel with something like a smaller, less destructive version of the plasma balls that annihilated the Klingons, and abducts navigator Lieutenant Illia (Persis Khambata, of Megaforce and Phoenix the Warrior). Shortly thereafter, an android duplicate of Illia materializes aboard the Enterprise to facilitate communications. The alien is a living machine that calls itself “V’Ger,” and it is coming to Earth to search for “the Creator.” It seems unlikely to say the least that anything Terrestrial could have made such a device as this, but V’Ger is certain that the Creator is to be found there— and evidently it’s not talking about a human, anyway, because it considers the “carbon units” crawling, swimming, flying, and sprouting all over the planet to be a parasitic infestation. There are just a few hours left before V’Ger reaches Earth now, which means just a few hours in which to solve the mystery of its seemingly impossible mission, and to convince it not to cleanse the Creator’s world of what it sees as a foreign pestilence. James Kirk has more experience than most people in outwitting sentient computers, but he never faced one with this short a fuse or this much firepower before.

If you have any firsthand familiarity with “Star Trek,” you know that encounters with godlike aliens are a persistent hallmark of the series. Hell, when “Star Trek: The Next Generation” debuted in 1987, the writers of the pilot made sure to cram in a godlike alien where one was neither needed nor wanted, just as a way of reassuring the viewers, “Here— you see? This totally is ‘Star Trek’!” Star Trek: The Motion Picture’s best feature is that it turns that longstanding series commonplace upside down. In this movie, V’Ger, for all its power, isn’t the godlike alien— we are. It turns out that in an interestingly roundabout way, the giant, living machine really is a human creation; fans of the original TV show will understand at once if I say that the movie is rather like a scaled-up and more optimistic version of the second-season episode, The Changeling. (Incidentally, the shot in which V’Ger’s true nature is revealed was a stunner in 1979, but has probably lost some of its power for modern viewers. Someone watching in 2013 would likely recognize the kind of thing that V’Ger used to be, but we who saw Star Trek: The Motion Picture in the 70’s or early 80’s knew that specific gizmo very well from its frequent appearances on the TV news.) The mind that V’Ger has developed since it left Earth as an inanimate object 300 years before doesn’t understand what it or its Creator really was. It knows merely that the Creator gave it a mission, and where to find the Creator now that that mission is complete. The conflict stems from the one thing that V’Ger has in common with humans. Having no direct experience of gods, it has invented one in its own image, and it is therefore unable to recognize its true creators (or their descendants, anyway) when it finally meets them. Of course, to be fair to V’Ger, for a being such as it has become, we have to make some pretty disappointing deities. It is therefore a thematically satisfying denouement when one of us steps up to the challenge of becoming the kind of Creator V’Ger requires, if not exactly the kind it was expecting.

Intellectually speaking, then, Star Trek: The Motion Picture is a more than worthy continuation of the 60’s TV show. It plays on one of the program’s most characteristic tropes in a potentially exciting new way, with subtle callbacks to at least three of its best episodes. (In addition to the aforementioned overt nods to The Changeling and The Doomsday Machine, you’ll spot a touch of Devil in the Dark in here, too, if you look closely.) It presents the Enterprise crew thinking their way out of an apocalyptic fix against impossible odds, with only a single photon torpedo fired— and that one merely at an inconvenient asteroid. And most of all, it is suffused throughout with the hopeful and humanistic spirit that ties the original “Star Trek” to the Robert W. Campbell tradition of science fiction, wherein the underlying assumption is that the future will bring out what’s best in our species. So why does this movie feel like so much more of a chore to watch than even its really dreadful sequels, like Star Trek V: The Final Frontier?

The first problem lies in the provenance of the screenplay. Alan Dean Foster’s version of this story was meant to air in a two-hour timeslot, but an “hour” of television meant 48 minutes of actual content in the late 1970’s. Had Harold Livingston (who adapted Foster’s “Star Trek, Phase II” pilot for the big screen) and director Robert Wise kept Star Trek: The Motion Picture to something like the intended 96 minutes, I suspect it would have come closer to the sleek efficiency of “Star Trek” on TV. At the two-hour-plus running time of a 70’s “event” movie, though, the same story feels bloated and baggy, and what’s worse, far too many of the little twists and turns are wasted. Dr. McCoy’s conscription, for example. McCoy’s introductory scene makes a very big deal of how unhappy he is to be brought out of retirement, and sets up a major current of resentment between him and his old friend, Kirk. That ought to matter, but it never does. Or look at all the attention the movie lavishes on the post-refit Enterprise’s teething troubles. The transporter malfunction serves to eliminate Spock’s replacement, and the buggy warp drive establishes the full magnitude of Kirk’s egotism, but ultimately those are dead ends. No significant plot point ever hinges on whether or not the ship’s systems are working properly, there’s no reason for Spock to be retired in the first place except that the writers had gotten used to the idea that Nimoy wouldn’t be back for “Star Trek, Phase II,” and it’s not like Kirk becomes either more or less of an arrogant self-promoter as a result of this mission. The biggest waste of all, though, is the Decker-Illia business. Yes, they were supposed to be major, regular characters on “Phase II,” and the producers probably felt like they owed something to Stephen Collins and Persis Khambata (who had already been cast for the aborted TV show) as a consequence. For the purposes of this movie, though, Decker and Illia might as well be any old pair of red-shirted ensigns, so there’s really no profit in belaboring their current relationship and mutual history the way Livingston and Wise do.

Star Trek: The Motion Picture gets the tone seriously wrong, too. The 60’s “Star Trek” always had a certain looseness about it, an air of experimentation, improvisation, making do, and getting away with stuff. It was a serious show more or less, in the sense that it rarely delved into outright comedy, but it didn’t take itself too seriously, if you see the distinction. The feature film, in contrast, is serious almost to the point of piety. Like I said, it takes many of its cues from 2001: A Space Odyssey, and although that wasn’t an unreasonable thing for a space-travel movie to do in 1979, it meant sacrificing the playfulness of original-recipe “Trek.” What once was presented as an adventure now feels uncomfortably like going to church— and one of those stuffy, upper-middle-class Anglican churches that Monty Python were so adept at spoofing, at that! Far too much energy is spent trying to inflict wonder upon the audience, be it in the form of a wormhole, a plasma nebula, the V’Ger spacecraft, or even the Enterprise itself. It gets to the point where you actually dread the big special effects set-pieces, because apart from the fairly tense opening confrontation between V’Ger and the Klingons, they invariably bring the film to a dead halt. You can almost hear Wise give the order to his own helmsman: “Main engines— full reverse!”

That said, I can understand to some extent the counterproductive emphasis on empty spectacle in Star Trek: The Motion Picture. For one thing, the models, the matte paintings, and all the various forms of optical trickery here are legitimately gorgeous; Paramount surely got their money’s worth from the effects shops. The revamped Enterprise in particular is one of the very few just-for-the-hell-of-it updates of an iconic piece of production design I can think of that actually improves on the original. But I think there’s also a psychological dimension to all the effects porn in this movie. Remember that budget figure I mentioned before for the TV series— $193,000 per episode— and realize that it represented the high point. In the third season, it was more like 178K each. To understand what that meant in practical terms, consider the case of the Romulan Bird of Prey. The first appearance of the Romulans was in a first-season episode called Balance of Terror, in which they were shown operating small, flattened ships rather like a winged flying saucer, with huge, yellow raptors painted across the underside. But when they turn up for the third and final time in The Enterprise Incident, they’ve traded in their Birds of Prey for Klingon cruisers, ostensibly because the Klingon ships had room to accommodate the Romulans’ newly developed cloaking device— which makes absolutely no sense, since the Romulans always had cloaking devices aboard their ships. The real, behind-the-scenes reason for the switch was that the prop warehouse had somehow lost the model for the Romulan Bird of Prey, and $178,000 wouldn’t stretch far enough to cover a replacement on top of all the regular operating expenses! So now think about a budget two orders of magnitude greater, and about how that much money might affect the outlook of people who had worked on the original series, or who had been fans before coming to work on the movie. In their place, don’t you think you’d go a little nuts, too, with all the stuff the TV effects department could never afford to show? Forgivable or not, though, Star Trek: The Motion Picture’s insatiable appetite for ogling things rapidly becomes its most exasperating feature, and a serious detriment to its effectiveness as anything beyond a testament to how high the bar had risen for acceptable production values in sci-fi since the 1960’s.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact