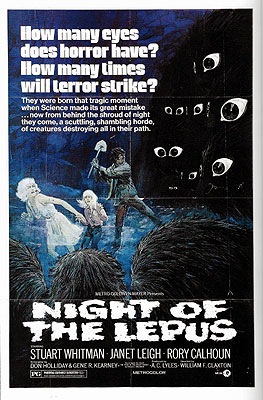

Night of the Lepus (1972) -***½

Night of the Lepus (1972) -***½

Most people, when they say that a movie seems impossible, are referring to the film’s subject matter. They’re saying that the events portrayed in the movie could not happen in the real world. I, on the other hand, am scarcely fazed by such things anymore. Here at 1000 Misspent Hours and Counting, we’ve seen more toxic and atomic monsters than I care to count. We’ve seen houses besieged by sometimes-invisible, leaping killer brains. We’ve seen cowboys fighting dinosaurs, zombies fighting cannibals, the Australian Outback terrorized by a giant, man-eating pig. We’ve seen a vampire prowling around a Portuguese island administering lethal blowjobs, for God’s sake! At this late stage of the game, my ability to suspend disbelief is formidable indeed. So when I say that Night of the Lepus seems impossible, I’m talking about something other than the plausibility of its story, although plausibility does bear directly on what I’m getting at. What I mean is that the movie’s very existence would seem to require a sudden outbreak of insanity on the part of untold dozens of people, an outbreak which would either have to last for a good long while or be repeated at regular intervals. The world is full of monster movies, nature-run-amok movies, and science-run-amok movies, and I’ve seen more than my fair share of all of them. But I have seen only one such movie that involved an army of giant, killer rabbits overrunning Arizona.

Yes, you read that right-- giant, killer rabbits overrunning Arizona. As the faux newscast that opens the film explains, Homo sapiens was not the only species poised for a huge population explosion in the early 1970’s. The rabbits of the American Southwest, which have been breeding like... well, rabbits, are beginning to pose a problem for their human neighbors, the ranchers. In fact, as the movie begins, one of those ranchers-- a certain Cole Hillman (Rory Calhoun, star of a zillion 50’s westerns, who would finish off his career making movies like Motel Hell and Hell Comes to Frogtown)-- is thrown from his horse when the unfortunate animal trips on one of the rabbits’ burrows, breaking its leg. After shooting his horse and walking home, Hillman places a call to his old buddy Elgin Clark (DeForest Kelly, of “Star Trek” fame), the president of the university that he attended in his youth, and to which he is now a major contributor. What Hillman wants from Elgin is for the college president to send one of his biologists around to look into getting rid of his rabbits. Hillman, you see, is a good, environmentally aware, modern rancher, and he would rather not dump cyanide all over his land the way his father would have back in the 40’s had he encountered a similar problem. Elgin promises to send him one of his best men, a scientist by the name of Roy Bennett (Stuart Whitman, another washed-up action hero who ended up making movies like Demonoid and Guyana: Cult of the Damned, where he played the Jim Jones character).

Bennett is on the cutting edge of research in the field of ecologically sound pest control. When we first see him, he is trying to trap bats and record their distress calls in the hope that loudspeakers playing this panic-inducing signal may be of use in herding the bats into areas plagued by flying insects. His wife, Jerry (Janet Leigh, of Psycho and The Fog), and his daughter, Amanda, are with him in the field when Elgin comes calling. After a moment of resistance, Bennett agrees to have a look at Hillman’s property and see what can be done.

The prognosis is not good. Hillman’s ranch is absolutely infested with rabbits, to the extent that they have eaten literally every blade of grass on much of his territory. Hillman’s men have been doing what they can by snaring and shooting the rabbits, but there are simply too damned many of them. Bennett and Hillman agree that trying to poison the rabbits would be a disaster, and the scientist quickly sets his mind to the problem of population control through less orthodox means. At first, he considers introducing a rabbit-specific disease into the area, but he ultimately rejects that idea as too risky. Then he tries a hormonal approach, with the aim of reducing the animals’ fecundity. Pay close attention to the scene in Bennett’s lab where Jerry tries to explain to Amanda what her father is trying to do to the rabbits-- the plan is hilarious. When the girl asks what’s going on, Jerry tells her, “Well, your father is trying to make Jack a little more like Jill, and Jill a little more like Jack, so that they won’t have such big families.” Are you following me here? Do you grasp the implications? Bennett is trying to develop a strain of gay rabbits!!!! But the process is taking too long, so instead he turns to something completely experimental, shooting up one of the rabbits (“Not that one, Daddy! That’s my favorite!” Amanda implores. This line of dialogue was dubbed in after the scene was shot, I suppose in order to make subsequent events seem slightly less nonsensical.) with some serum or other that one of Bennett’s colleagues at another institution just shipped out to him. How experimental is this approach? Try this on for size: Bennett doesn’t even know what the chemical is supposed to do!

Now that’s clearly a pretty bad idea, but it begins to look even worse when Amanda switches the treated rabbit (her favorite, remember) with an animal from the control group, and then wheedles her parents into letting her adopt a control animal (guess which one) as a pet. Place your bets, folks-- how long will it take for the rabbit to escape from Amanda’s clutches and run off to join its fellows in the wild? Would you believe it happens in the very next scene? And then, moving right along, Amanda goes out with Hillman’s son to visit a crazy old man who lives by an abandoned gold mine. (I don’t know how much time is supposed to elapse between the escape of the rabbit and the visit to “Captain Billy” but it must surely be longer than the hour and a half or so that the movie seems to imply-- not even rabbits breed that prolifically!) There is, of course, no sign of Captain Billy, but down in the mineshaft, there are a bunch of really huge rabbits-- at least as big as a man. Amanda freaks out and goes into shock when she sees this, and Hillman’s son has to bring her back home to her parents.

The adults spend the next couple of scenes putting their heads together on the subject of how much credence to assign to the girl’s tale of colossal bunnies in the mine. Their deliberations take on an added urgency when two mangled bodies are found, Captain Billy’s and that of a truck driver who stopped by the side of the road for no reason that I can fathom, other than to advance the plot by being killed by the rabbits. (And by the way, look in the back of his truck when he opens the tailgate-- it’s full of boxes marked “carrots!”) After consulting with the local medical examiner (This town needs a better one of those. Not only does he reply “Possibly” when the sheriff asks him facetiously if “some kind of vampire” gnawed the trucker to death, he also says-- in all seriousness-- that the only thing he knows of that could do such damage to a man is a sabre-toothed tiger!) and with another scientist (just look at that man’s hair!), Bennett, Hillman, and Elgin decide to go to the mine themselves and blow it up, sealing up whatever may be inside.

What’s inside is, of course, several thousand giant rabbits. Talking about this scene, which marks the creatures’ first appearance en masse, would seem to provide as good an excuse as any to say something about the special effects used to create them. Director William F. Claxton (more a TV director than a theatrical filmmaker) is a man after Bert I. Gordon’s own heart, and for the most part, his monster bunnies are the real thing, made to stampede in slow motion through miniature sets in a vain attempt to make them look big, and with moderate quantities of foam and blood applied to their lips in an equally vain attempt to make them look dangerous. Now that’s pretty fucking funny, but it isn’t the half of it. You see, some of the shots later on in the movie will require the rabbits to interact directly with the characters, doing things like trying to kill them. The difficulties involved in doing this with real rabbits, which after all are at best one tenth the size of the humans they would have to attack, should be self-evident. I think you know where this is going. Oh yeah-- we’ve got men in bunny suits, all right. And in a few shots, Claxton will allow the camera to linger on this ill-conceived special effect for an entirely excessive length of time, more than long enough for you to notice the curiously humanoid build of the rabbit onscreen. And we won’t have to wait long to see this awesome sight, either; when Hillman and Bennett go into the mine to have a look around, they are attacked, as are a few members of the supporting cast when one of the rabbits burrows out of the ground beside Captain Billy’s old shack. (Okay, everyone, say it with me: “I knew I should have made that left turn at Albuquerque!”)

They do manage to blow up the mine, though, and as far as the characters know, that’s the end of that. All that remains now is surviving the firestorm of bad publicity that is sure to follow when word gets out that the efforts of an environmentally conscious scientist to control a “rabbit explosion” (and that’s actually what they call it!) in an ecologically responsible manner accidentally led to the creation of thousands of unnatural monsters. But wait just one second. Where, exactly, do rabbits make their homes? That’s right, underground. And how, pray tell, do rabbits get underground? You got it-- they burrow. So why don’t you tell me what you think the chances are that you could effectively eliminate the threat posed by a burrowing animal by burying it under the ground...

So, yeah. The rabbits dig their way out of the mine. And having done so, they proceed to overrun quite a bit of Arizona, moving across the state in a pair of fronts, each at least a couple of miles wide. They attack ranches, general stores, entire towns. They cause stampedes of both horses and cattle. They damn near eat Jerry and Amanda Bennett when their camper gets stuck in a rut on the dirt road to a town supposedly out of the path of the rabbits’ advance. And in an economy measure endorsed by Bert I. Gordon himself, most of the destruction attendant upon the rabbits’ rampage happens off-screen. Finally, the National Guard is called in to deal with the situation (I knew it! Those damned rabbits are protesting the Vietnam War!), though the local garrison lacks the necessary manpower to contain the beasts. The solution ultimately adopted is in the finest 50’s tradition: a combination of machine gun fire and automobile headlights is used to channel the rabbits’ advance toward a two-mile stretch of railroad track through which a powerful electrical current has been routed. The overlay of the sparks and electrical arcs that signify the cooking of the killer bunnies is one of the worst image-compositing jobs I have ever seen.

The question still remains-- how on Earth could this movie have gotten made? Twenty years later, this idea could perhaps have got an airing as a tongue-in-cheek monster-movie satire, along the lines of Ticks or Skeeter, but-- and this is very important-- that’s not what happened here. Night of the Lepus plays out its thoroughly ridiculous story with a completely straight face. This movie is an utterly serious 70’s eco-horror flick, like Day of the Animals, or all of those terrible killer bee movies. And compounding my flabbergastation, Night of the Lepus was made for MGM Studios and it was based on a novel! You want to know what that novel was called? Would you believe Year of the Angry Rabbit?!?! Think about it; not only was MGM willing to throw money at this idea to make a movie out of it, Russell Braddon had already managed to convince somebody to send this display of sheer lunacy out into the world in printed form. I’m too young to have many first-hand memories of the 1970’s, but shit like this makes me miss them with a profundity that goes beyond ordinary nostalgia.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact