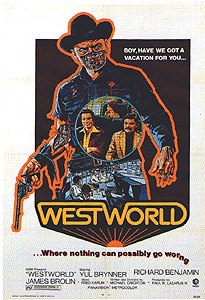

Westworld (1973) ***˝

Westworld (1973) ***˝

Okay, so I guess there are three things you can do to a western that will make me like it. To the previous “throw in a vampire” and “throw in some dinosaurs,” add “turn it into a science fiction movie, and make the black-hat gunslinger a killer robot.” What we have here is another Michael Crichton movie from the 70’s, and while Westworld doesn’t offer anything close to the intellectual integrity of The Andromeda Strain, it still serves to illustrate just how far its writer/director has slipped in the intervening 30 years. What is especially remarkable, in the context of Crichton’s career, is how close Westworld comes to looking like the superior demo version of Jurassic Park. In both cases, a bunch of “geniuses” who aren’t quite as smart as they think they are attempt to create the ultimate amusement park by exploiting hyper-advanced technology, only to have the fruits of that technology turn on them and their customers with catastrophic results. Both films are also compromised by a premise that seems brilliant at first glance, but begins crumbling immediately under close examination, but Westworld, unlike Jurassic Park, has more than one card in its hand as a movie of ideas, with the result that the film as a whole still comes across as smart even after its potentially damning central stupidity has been exposed. And of the greatest importance, Westworld has more genuine dramatic kick to it than any other Crichton picture I’ve seen.

Those who saw the trailers were seduced with the line, “Westworld— the ultimate resort. Where nothing— nothing— can possibly go wrong,” but in point of fact, Westworld is but one element of the most ambitious scheme in the history of the modern amusement park. For $1000 per day (adjust that figure upward by a factor of ten or so for the equivalent in today’s dollars), jaded vacationers may lose themselves in a totally immersive and totally authentic historical adventure, in a setting of their choice. Westworld offers the two-fisted ruggedness of an 1880’s frontier town; Medievalworld recreates the romance and danger of 13th-century Europe; and Romanworld promises “a lusty treat for the senses in the decadence of the imperial Roman Empire.” (I still haven’t figured out whether “imperial Roman Empire” is a screw-up or a joke; either way, it’s exactly what you’d expect from an early-70’s promotional copywriter.) The real draw, however, is that in all three venues, the Delos theme park is peopled by androids nearly indistinguishable from real human beings, enabling the customers to act out their most antisocial forbidden fantasies. You want to rob a bank? Break out of prison? Mistreat a slave? Kill a man in a chivalrous duel? Well you can do all that and more at Delos. The resort is located in what appears to be the middle of the great nowhere that is North America’s southwestern desert, far away from the settings of everyday life, and we may assume that as with Las Vegas, what happens at Delos stays at Delos. The three separate zones of this marvel of high-tech hedonism are all coordinated from an underground control station, where a staff led by the guy who used to be the voice of Mighty Mouse (Alan Oppenheimer, who can also be seen as well as heard in Trancers 4: Jack of Swords and Trancers 5: Sudden Deth) keep tabs on the actions of all the robots and repair those that are wrecked during the course of each day’s mayhem.

Among the latest crop of Delos customers, the ones in whose company we’ll be spending the most time are Peter Martin (Richard Benjamin) and John Blane (James Brolin, from The Amityville Horror and The Boston Strangler)— and since these guys have chosen Westworld as their vacation spot, I rather suspect that the phonetic similarity between “John Blane” and “John Wayne” is not accidental. Both men hail from Chicago, where Peter works as a lawyer, and where John must do something equally remunerative if he can afford to blow four or five grand on a long weekend out of town. This is actually Blane’s second trip to Westworld, and his motivation in bringing Martin along seems not unlike that of Lewis in leading his pals on that ill-advised canoeing trip in Deliverance— Martin’s too soft, and is in desperate need of some Manly Man action, especially after his recent divorce. And as it happens, the course of these men’s vacation holds a lot of remarkably close parallels with what happens in Deliverance. It starts off being all fun and games, with our heroes shooting down a menacing gunslinger (Yul Brynner, from The Ultimate Warrior), busting Martin out of jail, and carousing with Miss Carrie the mecha-madame (Majel Barrett, the wife of “Star Trek” creator Gene Rodenberry) and her robot whores, but things turn unexpectedly deadly after some three days at the resort.

The customers don’t know this, but the robots of Delos have been malfunctioning with increasing regularity of late, and the malfunctions seem to be spreading almost like a virus. (Note that I’m pretty sure 1973 was well before the advent of computer viruses as we now know them.) The early malfunctions were minor, but more and more of them have been concerning the androids’ central directives, and the boss downstairs is starting to worry. Some schmuck (Blood Legacy’s Norman Bartold, in a bit-part somewhat more substantial than the one he had in Close Encounters of the Third Kind) staying in Medievalworld attempts to seduce one of the sexbots (Anne Randall, of Hell’s Bloody Devils and The Night Strangler), and gets slapped in the face when he won’t take no for an answer; needless to say, “no” isn’t even supposed to be in a sexbot’s vocabulary. Then Blane gets bitten by a mechanical rattlesnake, which was supposed to be programmed always to miss on its strikes. Finally, the Medievalworld schmuck has a showdown with the Black Knight (Michael Mikler), and winds up with a broadsword through his gut! That signals the onset of a full-scale robot revolt, and the control staff’s efforts to correct the problem result only in their becoming trapped underground behind airtight, electronically operated doors that won’t accept commands from the main computer either. Finally, Blane and Martin return from a sojourn in the desert outside of town to find Westworld seemingly empty of everyone save their old friend, the gunslinger. This time, they’re going to find out how robot reflexes really affect the outcome of a quick-draw contest.

The main fault any reasonably thoughtful viewer is likely to find with Westworld is the thoroughgoing implausibility of the mechanics of Delos. Let us be charitable, and chalk the near-perfect simulacra of living human beings up to willing suspension of disbelief. That still leaves the problem of capital overhead, as the robots must cost millions of dollars each to construct, and many if not most of them will be ruined each day in gunfights, duels, and jousts, to say nothing of the inevitable routine breakdowns. The $1000-a-day price tag, meanwhile, places a very low cap on the number of customers which Delos can attract, with the result that a theme-park like this one simply could never be profitable. Then there’s the matter of safety. We are told that the pistols handed out to customers in Westworld are fitted with infrared sensors that disable the trigger mechanism when the gun is pointed at anything warmer than room temperature. That’s all well and good, but bullets do ricochet, and at close range, a .45-caliber shell is easily capable of passing completely through a human (or android) body— and will usually do so on a substantially different trajectory than that on which it entered. There’s no way to control for the surprisingly erratic behavior of a bullet in flight, and I can think of no safety mechanism at all to reduce the danger posed by a broadsword or a morning star while preserving their essential functionality. Finally, one might ask why the robots are apparently issued weapons without safety modifications— I mean, Yul Brynner never has trouble drawing down on a 98-degree target! Oh, and speaking of 98 degrees… To all appearances, Delos is located in Arizona or Utah or some such place; for most of the day through much of the year, the ambient air temperature ought to be at least that of the human body, making a mockery of any infrared-based failsafe system. I’d hate to see the resort’s insurance bills.

However, scoff-worthy though Delos may be in its nitty-gritty details, there is one thing about it that is disturbingly believable, and this is half of what makes Westworld work anyway. The appeal of such a resort, where the impulses to sex and violence may be freely indulged without consequences of any kind, is very easy to see, at least for a certain segment of the population. The people who keep paint-ball courses and shooting ranges and sparring gyms in business, the ones who make up the clientele for swingers’ clubs and bondage dungeons and even kinkier operations like Dick Drost’s Naked City— I’m thinking those who could afford to would line up around the block in the event that a resort like Delos became a reality. Westworld breaks down the customer demographics in a rather peculiar way (my guess is that Medievalworld would actually bring in the most women, while Westworld would be an almost exclusively male affair), but Crichton seems to have a pretty solid understanding of the movie’s most important sociological question: what would draw a man to Westworld? Especially when seen through the prism of the early 70’s, Westworld looks like the ultimate fantasy for men who fear that modernity means the end of masculinity, and because of that, it’s interesting that traditional machismo proves so totally unavailing when the robots go berserk.

The other half of Westworld’s salvation is those berserk robots, or more properly one berserk robot in particular. Even when we know he can’t do anything, Yul Brynner’s mechanical gunslinger is a frightening presence. Brynner had made scads of westerns when he was younger (he was almost 60 years old when Westworld was shot, although you’d never guess it from looking at him), and he appears to have been cast for the gunslinger’s part in a conscious effort to capitalize on that history. Even leaving aside the character’s telescopic infrared vision, low-amplitude hearing, and computerized reflexes, Brynner comes across here as quite possibly the baddest motherfucker ever to walk the Earth, and during his final-act pursuit of the last surviving tourist, he’s like a Wild West version of the Terminator. In fact, I’d be very surprised if Westworld had not been lurking somewhere in the back of James Cameron’s brain while The Terminator was shooting. Like Arnold Schwarzenegger eleven years later, Brynner has the implacable, unstoppable killing machine thing down pat, and he seems to do it with nothing more than a slight stiffening of the traditional western-movie bad guy swagger and a little help from a pair of unobtrusively creepy silver contact lenses. I, for one, would forget all about the spilled whiskey, and just find another seat on the other side of the saloon.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact