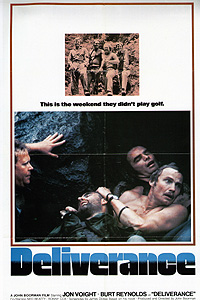

Deliverance (1972) ***˝

Deliverance (1972) ***˝

It’s amazing to me how many of the more intensely frowned-upon categories of 1970’s exploitation movies were effectively spawned by comparatively respectable, more-or-less mainstream films. Sure, Cotton Comes to Harlem and Sweet Sweetback’s Baad Asssss Song got there first, but it was really Shaft that got the blaxploitation ball rolling. The Man from Deep River, the first of the Italian cannibal movies, borrows a great deal from A Man Called Horse, even if its roots sink deepest into the more sinister soil of the mondo “documentary.” The nunsploitation movie, possibly the sleaziest of all the new growth of the 70’s, owes its existence to Ken Russell, of all people. And in an especially stark illustration of one of cinema’s more annoying double standards, the hillbilly horror strain exemplified by such roundly castigated movies as The Hills Have Eyes and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre has an obvious immediate antecedent in John Boorman’s Deliverance, one of the most critically acclaimed films of its era. Don’t misunderstand me— Deliverance is a great movie, and deserves the praise it’s been given. But it bugs the hell out of me that, in the eyes of the professional critics, Wes Craven and Tobe Hooper are pandering to the worst impulses of humanity when they make movies about city people turning savage in order to survive a brutal attack by redneck psychopaths, yet when Boorman does essentially the same thing and just tarts it up slightly with some facile pseudo-Marxist class-struggle rhetoric, he’s making High Art and his work gets nominated for a bunch of academy awards.

But enough grumbling… The city folks here are 35-ish professional types Lewis (Burt Reynolds, who didn’t get nearly as much positive recognition when he appeared in Shark! and White Lightning), Ed (Jon Voight, later of Anaconda and Transformers), Drew (Ronny Cox, from The Car and The Beast Within), and Bobby (Ned Beatty, whose more embarrassing credits include Exorcist II: The Heretic and Rolling Vengeance). The reason they’re leaving their comfortable homes in the Atlanta suburbs for what will end up being a disastrous foray into the countryside is that “the last wild, untamed, unpolluted, un-fucked-up river in the South” is about to be dammed to provide hydroelectric power for the city and its satellites. Lewis, who fancies himself something of a modern primitive, sees this as his last chance to commune directly with the unfiltered wilderness, and he has somehow conned all three of his homebody buddies into joining him on a canoeing trip down the condemned river.

The first stop on their itinerary is a collection of crumbling shacks about two days’ travel upstream from the projected site of the dam. The idea here is to gas up the two cars and then hire somebody to drive them down to the vicinity of the dam to await their owners’ arrival. Considering that this stop also marks the vacationers’ first interaction with the locals, I can’t say it augurs terribly well for the rest of the trip. The mountain people are visibly suspicious of the outsiders, whom they associate with the power company whose new dam is about to put their age-old homes at the bottom of an artificial lake. Beyond that, Ed and Bobby do just about everything in their power to convey their contempt for the hillbillies, while Lewis comes across with so much alpha-male arrogance that his companions fear an outburst of violence erupting at any moment. The tension is diffused only when Drew, who is tuning his guitar while he waits for the gas tanks to fill, provokes an impromptu round of “Dueling Banjos” with a young halfwit (who plays a mean banjo despite his retardation). Even so, the man who ultimately agrees to drive the cars downstream is openly hostile in his haggling with Lewis, and he issues some odd, cryptic warnings about how much the men from Atlanta are going to regret heading down the river.

In point of fact, the redneck with the tow truck has hit that particular nail squarely on the head. There are not words for how much regret Lewis and company will come to attach to this weekend’s excursion. Things go well for the first day, what with the fishing and the canoeing and the beer-drinking and the overall getting in touch with their inner barbarians. But on day two, Ed and Bobby (visibly the least competent of the foursome) get separated from Lewis and Drew. When they pull over to the bank to take a rest, they encounter a pair of armed hillbillies who had been wandering around in the woods, possibly hunting. When these hillbillies notice that they have company, they turn their shotgun on Ed and Bobby, ordering them away from the riverbank and deeper into the woods. Once they’re well out of sight from the water, the mountain men tie Ed to a tree and make him look on while one of them forcibly sodomizes Bobby. Then it’s Ed’s turn. The rednecks switch places, the one who raped Bobby holding the gun on Ed and commanding him to kneel as the other undoes the fly of his pants and comments on what a “pretty mouth” his victim-to-be has. What neither redneck rapist realizes is that Lewis and Drew have by this point spotted their companions’ derelict canoe and followed their trail into the woods. And of greater importance still, Lewis is even now silently drawing down on the gunman with his hunting bow. The shaft flies straight through its target’s heart, and the dead man’s accomplice loses all interest in coerced blowjobs for the moment.

Lewis, Drew, Ed, and Bobby are now faced with an uncomfortable choice. The civilized thing to do would be to pack the body up and take it to the police. A civilized man would then explain that the killing was committed in defense against an armed rapist, and trust in the machinery of the state to reach a just resolution. But as Lewis passionately argues, he and his friends are beyond the reach of civilization. If they go to the police, they’ll be held in the county jail pending trial before a jury of the dead man’s cousins, aunts, and brothers-in-law— and can anyone honestly doubt what’s going to happen then? And even if Lewis is wrong about that, going to law will mean exposing the story of Bobby’s humiliation, and of the humiliation only narrowly avoided by Ed. Neither man wants that, and one suspects that it is this fear of admitting what happened that sways them, far more than the parallel line of reasoning regarding the nearly foreordained outcome of a jury trial. Drew argues against it to the very end, but he digs harder than anyone when the final vote is taken and the decision is made to bury the rapist’s body in a shallow grave in the depths of the forest. It should be obvious, however, that our heroes’ travails are far from over. The second hillbilly is still out there somewhere, and while Lewis is probably right about him being none too eager himself to go to the cops, there’s nothing at all to stop him from taking matters into his own hands. After all, this is Appalachia we’re talking about— blood-feud country.

John Boorman is a director about whom it is completely appropriate to say that there are two sides to his nature. On the one hand, he’s made some very serious, very well-received films. On the other hand, he also made Zardoz and Exorcist II: The Heretic. Deliverance falls firmly into the former category, and there’s a good chance that it represents the best work the director ever did. Though it seems to me that its current position within the cult-film canon derives more from its inspirational value than from any of its own intrinsic qualities, and that Deliverance is better understood as the serious rumination on class conflict and post-industrial masculinity that it was reckoned to be at the time of its release, it nevertheless has a grimness and toughness about it that are rare among mainstream movies that deliberately deal in Big Ideas and Deep Thoughts. In that sense if no other, it is akin to all the grindhouse backwoods horror films which it midwifed over the ensuing decade. The struggle for survival into which the protagonists’ weekend in the wilderness devolves is portrayed with a raw edge that still surprises today, and which must have seemed outright shocking in the early 70’s, even though shock per se is not this movie’s primary aim.

No, the primary aim here is to consider consciously the question that lurks in the background of movies like The Hills Have Eyes: is modern man too soft to survive without the apparatus of civilization to back him up? And layered atop that question is a second theme which is also visible in the corners and crevices of later city-vs.-country horror films, the positing of a confrontation between affluent townspeople and the downtrodden rural folk who resent their wealth and comfort as the main question’s ultimate test-case. In fact, Deliverance carries the dual theme a step further by explicitly acknowledging that Lewis and his friends gain their easy existence directly at the expense of the mountain men against whom they will have to fight for their lives. Most of the time, I am automatically suspicious of Marxist analyses of mainstream American movies, but this is one case in which such a thing seems more or less justified. Certainly Boorman invites us to think in those terms when he opens Deliverance with a monologue from Lewis decrying the environmental consequences of the new hydroelectric dam, which unfolds over a series of images hinting at the unspoken human cost of this “progress.” Then later on, the sight of a small country hamlet being uprooted and bodily carried to higher, drier ground clinches the argument. On ecological and socioeconomic grounds, Deliverance essentially contends that the chain of affront and revenge begins not with the mountain men’s attack on Ed and Bobby, but with the destruction of the countryside to serve the material wants of the already much wealthier people of Atlanta— that Bobby’s rape was itself a justifiable act of vengeance. I’d contend that it’s a rather simplistic and one-sided claim that Boorman is making here (one might justly ask if anyone really benefits from the preservation of such a debased and self-defeating heritage as the Appalachian hellhole he depicts, for example), but his apparent line of reasoning would have sounded more novel (and perhaps more persuasive) in 1972 than it does today. In any case, I think it fairly obvious that Deliverance’s rather transparent effort to layer politics on top of exploitation explains much of the welcoming reception that greeted its release. It gave Boorman license to go for the throat (and the rectum, too, for that matter…) when a more direct treatment of the same subject would have won him little but opprobrium.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact