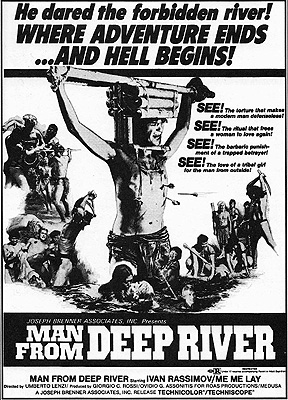

The Man from Deep River / Deep River Savages / Sacrifice! / Mondo Cannibale / Il Paese del Sesso Selvaggio (1972) ***

The Man from Deep River / Deep River Savages / Sacrifice! / Mondo Cannibale / Il Paese del Sesso Selvaggio (1972) ***

Many people seem to treat the Italian cannibal movie as a sort of cousin to the Italian zombie movie; occasionally, I’ve even heard the cannibal subgenre described as an offshoot of the zombie film. The trouble with this conceptualization is that many of the big-name cannibal movies appeared well before the Italian zombie boom kicked off with the release of Zombie in 1979, while the very first of the cannibal gut-munchers— Umberto Lenzi’s The Man from Deep River/Deep River Savages/Il Paese del Sesso Selvaggio— predates even Let Sleeping Corpses Lie. Consequently, it seems clear to me that the undeniable similarity between the two genres is a case not of direct kinship, but of what biologists call “convergent evolution.” All that leaves open the question of where exactly the Italian cannibal movie really came from, but I believe it is possible to answer that question by taking a good, close look at The Man from Deep River, the source from which the whole ugly business ultimately springs, for The Man from Deep River differs markedly from its descendants in an instantly recognizable way. Whereas most cannibal flicks roam the no man’s land between horror and adventure, The Man from Deep River (as its alternate Italian title would suggest) resembles nothing so much as a Mondo movie with a plot.

The Mondo craze, for the novices among you, began in 1963, with the release of Mondo Cane (the title means “Dog World,” perhaps in the same sense as the English phrase, “gone to the dogs”), an Italian exploitation documentary cataloguing bizarre behavior from around the world. Though nearly all of the footage in the original Mondo Cane was legitimate, the copycat films that flooded the market throughout the 1960’s and early 1970’s would rely to an ever greater extent upon material that was staged or even faked outright. But regardless of their authenticity quotient, most of the Mondo movies displayed a nearly obsessive focus on two things— cruelty to animals and the exotic rituals of Third-World primitives. Frequently, the two strains would be combined, as in the segment of one 60’s Mondo film that depicts a group of stone-agers slaughtering a stupendous number of hogs in preparation for the most important of their annual festivals. Interest in Mondo movies was already dying by 1972, however, probably because ordinary life in the Western world had itself become so bizarre that only the most grotesque and barbaric of the increasingly fraudulent documentaries retained any real power to shock. Around that time, it would appear that producer Ovidio Assonitis— probably looking back to the development of modern porn from the burlesque films and nudist documentaries of the 1950’s— got it into his head that what the Mondo picture needed in order to stay fresh was a story. The Man from Deep River thus begins with a title card explaining that there are primitive tribes living in the wilderness along the border between Burma and Thailand who have had almost no contact with the outside world, and which goes on to promise that the movie we are about to see was made with the cooperation and participation of one such tribe— “Only the story has been invented.”

That story begins with a Westerner named John Bradley (Ivan Rassimov, from Blade of the Ripper and Shock), a photographer from London on assignment in Bangkok. He and his date, Susan, are attending one of Thailand’s notoriously brutal kickboxing matches, and the woman has had quite enough of the unsettling spectacle. While Bradley is busy flagging down an arena employee in order to place a bet on the boxer in red trunks, Susan slips away and goes off with a burly Thai man who looks distinctly like trouble. Evidently she does not speak well of Bradley to her new companion, for he later tracks John down at a bar and threatens him with a switchblade. Drunk though he may be, Bradley is both fast and strong, and he defends himself with extraordinary success. Unfortunately for him, his defense is so successful that the Thai ends up dead, and Bradley is forced to go on the run. He flees all the way to the countryside along the Burmese frontier, and then hires himself a guide to take him on a tour up the nearest river; one assumes John figures he may as well get some pictures taken, even if he is a fugitive from the law.

The man in whose care John’s guide left his rickshaw before embarking upstream gave the Englishman a word of advice upon their parting: follow the river only so long as it remains wide. Any further than that, and a man takes his life in his hands. Bradley predictably disregards that advice, and no sooner has the boat passed into the narrow waters upstream than the guide is killed and John captured by warriors from a primitive tribe. The natives don’t seem to know what to make of John. They’ve evidently never seen a white man before, and they seem to have interpreted his wetsuit as a kind of skin. So far as Bradley can tell, his captors believe him to be some sort of exotic, intelligent fish! Obviously Bradley is in considerable danger at this point, but his luck is in to at least some small extent, in that he has caught the eye of the chief’s daughter, Maraya (Me Me Lai, from Crucible of Terror and Eaten Alive). Maraya insists that the warriors spare John’s life and hand him over for her personal use. True, that means slave labor on the construction of the hut where Maraya will live once she has come of age and taken a husband, but at least Bradley knows no one is going to kill him.

Then one night, after some months of work on the hut, Bradley is approached by an old woman (Pratitsak Singhara) who unexpectedly speaks to him in English. The woman explains that she was the half-breed child of a British missionary, who was adopted by the tribe after her father was killed by the warriors. She offers to help Bradley escape, but says that he will have to wait a while yet. John had been injured that day in a fist-fight with a native man, and he’ll need all of his health and strength if he’s going to make it past the cannibals who live on the other side of the mountain from his captors’ village. He makes his play to escape a few days later, but he doesn’t get very far. At the very edge of the tribe’s territory, he is surrounded by warriors, and though he kills their leader in single combat, the rest of the men are able to drag him back to the village with them. Even so, the day’s events make for a major change in John’s life, for his victory over the tribe’s greatest hunter has won him the respect of the other tribesmen, and he is swiftly initiated into tribal society. (Inevitably, this involves three days’ worth of arduous physical ordeals, ranging from being tied down in the sun all day without food or water to being shot with blowgun darts until he resembles a six-foot, humanoid pincushion.)

And now that he’s part of the tribe, John gets a chance to compete for Maraya’s hand in marriage. The tribe’s courtship ceremony is odd indeed. Maraya strips naked, and lies down beside an arm-sized hole in the wall of her newly completed hut. All the unmarried tribesmen then line up outside and take turns groping the girl through the hole; the winner is the man whose caresses please Maraya the most! Unsurprisingly, Bradley comes out on top. After all, Western women are in a position to be far more demanding than their stone-age counterparts, and John, as a man in his 30’s, has had years in which to practice his technique. The other contestants really never stood a chance. It turns out to be as happy a marriage as any cross-cultural pairing can be, and Maraya is soon pregnant with their first child. Alas, she’s also soon sick with some strange tropical illness, and the cannibals in the next village over start casting an acquisitive eye on Bradley’s adopted village at about the same time.

The first thing a true cannibal connoisseur will notice about The Man from Deep River is how far in the background the cannibalism is. Instead of the expected gut-munching bloodbath, what we get here is the standard Mondo movie parade of unpleasantness against animals and Weird ’n’ Wacky Tribal Customs, tarted up with a storyline cribbed more or less directly from the somewhat earlier A Man Called Horse. It’s an atypically well-made film, which treats the stone-age natives with an unusual amount of respect, but someone who comes to this movie looking for something like the grimmer and bloodier cannibal movies that followed it is likely to leave disappointed. In this respect, The Man from Deep River looks a lot more like the latecomer White Slave than it does like Make Them Die Slowly or Cannibal Holocaust, and what I said back in my review of Ruggero Deodato’s Jungle Holocaust seems even truer than I realized at the time. Deodato really did beat Lenzi at his own game, pinpointing exactly the most exploitable element of this movie and then running with it as far as his bosses at the studio would let him get away with. By the turn of the 80’s, even Lenzi himself would see how thoroughly he had been outmaneuvered; the director’s next two cannibal films would be far grislier, far more aggressive.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact