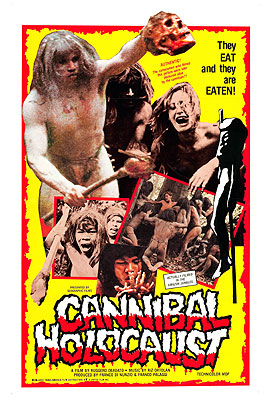

Cannibal Holocaust / Holocosto Cannibal (1979/1984) *****

Cannibal Holocaust / Holocosto Cannibal (1979/1984) *****

I tend to view most movies of the kind that I end up writing reviews of with a sort of wry humor, and I try to convey some sense of that attitude when I sit down to write about them. That said, I want to advise you not to look for any of that in this review, or in the film it discusses. Cannibal Holocaust is absolutely not, under any circumstances, a fun movie. It is beyond disturbing, a movie to be watched alone with the sort of sober attentiveness due a rattlesnake or a Moroccan fat-tailed scorpion. I have seen a fair number of Italian cannibal movies in my time-- Make Them Die Slowly, Cannibal Apocalypse, The Mountain of the Cannibal God, Dr. Butcher, M.D.-- plus a few quasi-cannibal flicks like White Slave and The Grim Reaper, but I seriously can’t recall ever having seen a film so uncompromisingly vicious, so unflinching in the face of its own hideousness in my entire B-movie-watching life. And believe me, coming from me, that is saying something.

This movie is divided fairly neatly into two sections, and today, its story is likely to remind people of a certain low-budget independent horror film that recently caused quite a stir because of the synergistic interaction of its mock-cinema verite approach and the unparalleled marketing savvy of its creators. Cannibal Holocaust begins with a TV news anchorman talking about a team of highly respected freelance telejournalists, led by director Alan Yates (Gabriel Yorke), who went to the Amazon basin to film a documentary about the local stone-age tribesmen and never came back. At the time of the news broadcast, the filmmakers have been missing for several months, and a distinguished anthropologist named Harold Monroe (cannibal movie regular Robert Kerman, who would do this again in Eaten Alive and Make Them Die Slowly), of New York University, has decided to embark on his own expedition in search of Yates and his companions.

When Dr. Monroe arrives in South America, the local paramilitary police authorities inform him that they have captured a man from the Yakumo tribe, an inhabitant of the region of the jungle where Yates’s team disappeared. Significantly, because the Yakumo have never been known to practice cannibalism, when the tribesman was found, he and several of his fellows were sitting around a campfire, far from their own territory, eating the remains of a human being. The policemen attacked the primitives, killing all but the one to whom they now introduce Dr. Monroe. Monroe decides to take the man along as a guide, in addition to Chaco (Salvatore Basile) and Martinez (Paolo Paoloni, from Inferno and Dr. Jekyll Likes Them Hot), the guides whom he had already hired.

This turns out to have been a wise decision, as the Yakumo prove unexpectedly hostile when Monroe and his guides finally reach them. Like all primitive peoples, the Yakumo are potentially dangerous, living in a world where human life is among the cheaper commodities (as the grisly execution of a young adulteress, which serves as our introduction to the Yakumo way of life, reminds us). But the hostility that confronts Monroe is unusually extreme for what is generally considered to be a fairly peaceful people. Indeed, it seems fairly likely that he, Chaco, and Martinez would have spent the trip home pulling poison darts out of their asses had they not had a hostage to trade. Even then, the Yakumo treat the outsiders with uncharacteristic suspicion-- later on, the reason will become abundantly clear. Nevertheless, Monroe learns from the Yakumo what he wanted to know. Yates had in fact been to their village, and his team had then continued upstream into a part of the jungle where the Yakumo fear to venture.

The Yakumo’s trepidation stems from the fact that that region is inhabited by two extremely fierce tribes of cannibals, the Yanomamo (the People of the Trees) and the Shamatari (the People of the Swamp), who war constantly with each other, and are both perfectly happy to kill and eat any other strangers they come across. That Yates and his people would venture into their land is eloquent testimony to their fearlessness and ambition.

Monroe and his guides continue following the trail until they, too, encounter the Yanomamo. By a stroke of luck, they arrive on the scene just in time to save a Yanomamo foraging party from an attack by Shamatari raiders, driving the latter cannibals off with their rifles. This is the first step in the difficult process by which Monroe ingratiates himself to the Yanomamo, a process that culminates in his joining them in a feast where the main course is the body of a Shamatari captive, and which pays off with the discovery in the Yanomamo’s territory of a totem made of the bones of Yates and his crew, along with their film and equipment. Monroe trades his tape recorder for the film (which the Yanomamo are perfectly happy to get rid of-- they believe it to be the source of Yates’s black magic, a revelation which should worry you at least a little bit), and returns to New York.

The rest of the movie, about half its running time, consists of Monroe watching Yates’s film in the company of various employees of some big, cynical TV network. Call it The Blair Cannibal Project, if you’d like. As the footage reveals with ever-increasing ghastliness, Yates and company more than earned their fate. The first troubling hint (after the revelation that the Yanomamo considered Yates an evil sorcerer) comes when one of the TV people tells Monroe that Yates had a reputation for doctoring his documentaries. He wasn’t exactly a fraud, but if he decided that his subject wasn’t exciting enough, he was not above steering events in a more sensational direction. But that doesn’t begin to describe his conduct in Amazonia. Yates’s jungle expedition was nothing less than a nihilistic rampage of terror for the sake of ratings, right from the moment when his guide, Felipe, was bitten by a poisonous snake, and Yates decided to treat the bite by amputating the man’s leg at the knee with his bolo knife.

The Yates party’s interaction with the natives was simply one atrocity after another. The director had hoped to film an attack by one or the other of the cannibal tribes on the Yakumo village, but when no such massacre was forthcoming, Yates opted to improvise by rounding up as many of the Yakumo as he could, herding them into one of the larger huts, and setting it ablaze, his cameras running the entire time. His treatment of the cannibals was no better. His first contact with the Tree People came when he encountered a lone Yanomamo girl by the riverbank. Again, an atrocity resulted, as he and his cameramen took turns filming each other raping the girl, even over the vociferous protests of Yates’s own fiancee (arguably the least evil of this degenerate crew). When Yates’s comrades begin to fall victim to the Yanomamo, their conduct only makes them seem even slimier. Yates himself films from a hideout in the brush as the cannibals emasculate his cameraman and then hack him to pieces with stone adzes. He does the same when his other companions are killed, even going so far as to film the gang-rape and dismemberment of his girlfriend. By the time the cannibals get their hands on Yates, we’re practically cheering for them.

On its face, this doesn’t sound too much different from the plot of Make Them Die Slowly, and on the surface, the two movies are very similar. But differences in tone make Cannibal Holocaust a beast of another species altogether. Make Them Die Slowly is brainlessly exploitative. Cannibal Holocaust is plenty exploitative, but it is a canny, manipulative exploitiveness that no other cannibal movie I know of has matched. The mainspring of this film is the horrific blurring of the line between fantasy and reality. To begin with, the half of the movie that is supposed to be Yates’s footage uses a different film stock from the framing story. This film stock is grainy, scratched, and discolored; its frame composition is imperfect and inconsistent; some scenes are over-exposed, some under-exposed; the sound comes and goes erratically, and is always underlain by the rattling of the camera’s internal machinery. The poor quality of the picture and sound add an extra layer of believability both by mimicking what you would expect from film that had been sitting undeveloped in its canisters in the jungle for four months, and by making it harder to spot the shortcomings of the gore effects. I’ve heard a story about an English reviewer who watched Cannibal Holocaust over and over again the day she went to see it in an attempt to find something to assure her that what she had seen was not real. That story may not be literally true, but it makes a great legend, conveying exactly the nature of this movie.

But there’s more to Cannibal Holocaust’s aura of ghoulish verisimilitude than sneaky camera tricks. You see, this film is laden with the most monstrous cruelty to animals that I have ever seen in a movie. I’m not talking about stock footage of animals eating each other, either. I’m talking about the actors in this movie actually killing actual animals right in front of the leering camera. A smallish snake is decapitated; a muskrat has its throat slit; a monkey’s skullcap is hacked off; and in the most loathsome sequence of all, Yates and company catch, butcher, cook, and eat an enormous turtle. I want you to understand me here. I’m neither an animal rights activist nor a vegan. I eat meat; I wear leather; I have taken biology and anatomy courses in which I have personally dissected earthworms, oysters, lampreys, sharks, perches, frogs, fetal pigs, rabbits, and even a cat that looked uncannily like a beloved childhood pet. I am no stranger to the arguments both for and against taking an instrumental view of animal life, and most of the time, I incline more toward the affirmative side of that debate than the negative. But I do recognize certain distinctions and boundaries, and the treatment of animals in this movie is hideous, unspeakable.

You may recall that in my review of Cannibal Apocalypse, I mentioned that this movie has actually been mistaken for a snuff film (and, hey, it is if you’re a turtle). Here’s the story, which I think is important for a complete understanding of this film. Director Ruggero Deodato shot Cannibal Holocaust in Venezuela, a part of the world that had a reputation as a point of origin for snuff films. Now think about this. A gore movie of unprecedented intensity comes along, shot in the jungles of Venezuela, positively loaded with nauseating animal cruelty that seems to say, “hey, if we were willing to do this...” Looked at in those terms, it’s scarcely surprising that, upon his return to Italy, Deodato was actually prosecuted for making this movie, while the Venezuelan authorities launched their own criminal investigation into the production of Cannibal Holocaust. Reportedly, Deodato had to round up the extras who had played several of the featured victims in order to prove that they were still alive. Meanwhile, in less vigilant parts of the world, the movie’s distributors drew up lurid advertising campaigns promising that it depicted real-life events, even if the movie itself was merely a dramatization of them. Makes the internet feeding-frenzy over The Blair Witch Project seem positively tame, doesn’t it?

Moral considerations aside, it seems inescapable to me that Cannibal Holocaust has a certain vile, monstrous genius about it. It may not be a good movie in the commonly understood sense of the term, and it certainly plays dirty, but this is a film that accomplishes exactly what it sets out to do. I have thus given it my highest rating, albeit with a certain amount of discomfort. I had looked for this movie literally for years, and I’m glad I finally saw it. But I’d be a liar if I said I had any particular desire to see Cannibal Holocaust again any time soon, maybe even ever. This is not a film you enjoy watching. If you do-- if you derive pleasure from the experience, as most of us understand pleasure-- it probably wouldn’t be a bad idea to seek out a mental health professional of some sort. No, really.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact