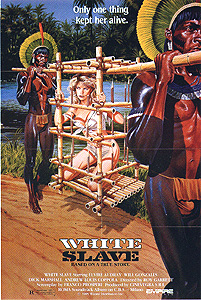

White Slave / Amazonia: The Katherine Miles Story / Captive Women VII: White Slave / Schiave Bianche: Violenza in Amazzonia (1984/1986) ***

White Slave / Amazonia: The Katherine Miles Story / Captive Women VII: White Slave / Schiave Bianche: Violenza in Amazzonia (1984/1986) ***

The Man from Deep River, the first of the Italian cannibal movies, concerned the experiences of a Western man whom circumstance forced to live among the stone-age tribesmen of the tropical rainforest. It seems somehow fitting, then, that the film which apparently served as the genre’s last gasp should also deal with this theme. Like many of its predecessors, White Slave/Amazonia: The Katherine Miles Story/Schiave Bianche: Violenza in Amazzonia claims to be based on a true story, in this case, that of a wealthy young English girl who spent months, or perhaps even years, as a captive of the Guainira tribe deep in the Brazilian jungle. Frankly, I see no reason to give any more credence to White Slave’s assertions of biographical veracity than I do to the similar claims made by Jungle Holocaust/Ultimo Mondo Cannibale, but I suppose just about anything’s possible.

The movie unfolds as a series of flashbacks within flashbacks, a structure which I will largely ignore in my synopsis, although it does add a bit of freshness to what would otherwise be an extremely derivative film. Eighteen-year-old Katherine Miles (Elvire Audray, from The Scorpion with Two Tails and Ironmaster) has come to Brazil to spend the summer with her plantation-owner parents. In celebration of both the girl’s homecoming and coming-of-age, her parents decide to take her on a tour of the river on their new houseboat; it’s been a long time since Katherine (who’s spent most of her young life in boarding schools) saw the jungle, and she used to love it so when she was a child. But tragedy strikes when Katherine, her parents, and her aunt and uncle get past the last outpost of civilization. The houseboat is suddenly engulfed in a hail of blowgun darts, and within minutes, Katherine’s parents are dead, and she herself has been incapacitated by the paralyzing frog-venom that tips the darts. (It is not clear at this point just what happened to Katherine’s aunt and uncle, who were riding in a smaller, canoe-like vessel behind the houseboat.) While Katherine lies paralyzed on the deck, the boat is boarded by a band of Indio warriors, who cut off her parents’ heads to serve as trophies, and who take her captive once their leader, Umukai (Alvaro Gonzales), figures out that she is still alive.

Thus begins Katherine’s long stay in the jungle. At first, the Guainira chief assigns her to the richest man in the village, in accordance with the tribe’s custom that the spoils of war be distributed on the basis of what gifts the chief receives from his followers in exchange. (Katherine, in case you were wondering, is worth a goose, a turtle, and a small, pig-like animal the Guainira call a “water dog.”) Mr. Moneybags never gets to enjoy his gift, however, because Katherine is a virgin, and the Guainira (who artificially deflower their girls at a very young age as a rite of passage) observe a taboo on copulating with women who still have hymens. By the time Katherine has undergone the ceremony and “become a woman,” Umukai has challenged her “rightful” owner for possession of her, and ultimately defeated him in single combat, winning the girl for himself.

I think you may have some idea where this is going. Umukai developed a serious crush on Katherine the moment he first saw her passed out on the deck of her parents’ boat. She, on the other hand, can’t stand Umukai, because he led the raid that killed her parents. Most of the movie from this point on deals with Katherine’s slow but undeniable assimilation into the Guainira, which is aided by Umukai’s sister, who spent her first seven years living among English-speaking missionaries, learning thereby a smattering of Katherine’s language. Conversely, Katherine’s knowledge of Western first-aid, which she displays by re-setting the broken leg of a man who had been among the Guainira’s most accomplished hunters before he was crippled, convinces the tribe that she possesses magical powers, further easing her transition from captive slave to valued member of tribal society. Over time, she will also gradually come to realize the level of indulgence with which Umukai treats her, and to grasp the depth of feeling that motivates it.

Eventually, when Katherine and Umukai have finally learned enough of each other’s tongues to communicate meaningfully, the warrior reveals something to her that completely changes the way she understands and relates to her situation. According to Umukai, he and his hunters came upon the houseboat while it was already under attack. More interesting is Umukai’s description of the real attackers— a white man, a white woman, and a pair of Indios in a large canoe. Katherine doesn’t believe Umukai at first, but once she’s had a chance to think about it a bit, she realizes how closely that description matches her aunt and uncle, who had been following her and her parents in a long, narrow boat with two pilots of Indio descent. Not only that, the terms of her father’s will make her aunt and uncle owners of the plantation in the event that both Katherine’s parents die. And finally, the girl’s aunt and uncle had a solid motive for speeding Mr. Miles along in his progress toward the grave: they were the paupers of the family, having lost everything they had through ill-considered investments. With all the pieces thus in place, Katherine’s long-dormant desire to avenge her parents comes flooding back to her, and her scheming relatives are soon to discover that being found out by the authorities is the least of their worries. The months of hard living as a head-hunter’s girlfriend have toughened Katherine considerably, and made her a pretty good shot with a bow and arrow as well. It all goes some way toward explaining the courtroom scenes that have been interrupting the action every fifteen minutes or so, wouldn’t you say?

On the whole, White Slave might be described as a kinder, gentler cannibal movie. Indeed, cannibalism itself rarely enters into the story (the Guainira’s arch-enemies from the next valley over are cannibals), and is never actually depicted. There’s still some fairly grisly violence on display here (after all, Katherine’s keepers are headhunters, even if they never go so far as to eat their victims), but the German audiences who saw this movie under the title Cannibal Holocaust 2 surely left the theater disappointed. There is, however, one very conspicuous point of similarity between White Slave and Ruggero Deodato’s cannibal films. Like them, White Slave takes the natives’ side when it comes to the question of whether the white man or the Indio is the true savage. In fact, White Slave goes even farther with this theme than Deodato’s work, and offers by far the most sympathetic, human portrayal of primitive people ever presented in a film of this type. Though the movie does not flinch from depicting the brutality of stone-age life, its creators also devoted much of their energy to showing the beauty of the Guainira’s world and Umukai’s uncomplicated devotion to Katherine. Meanwhile, “civilized” people are viewed with as jaundiced an eye as ever. Not only is the attack on Katherine’s family revealed to have been the work of avaricious relatives, there is also a lengthy scene in which the Guainira are shot at from a helicopter by a pair of bounty hunters working for a logging company. Significantly, these hired guns are required to furnish heads to their employers as proof of their success. White Slave remains a minor entry in the cannibal genre, but in marked contrast to the norm for such things, this final cannibal movie does not represent a significant drop-off in quality from most of its predecessors.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact