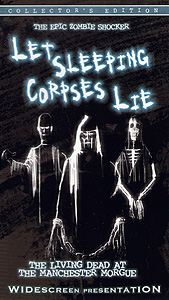

Let Sleeping Corpses Lie / The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue / Breakfast at the Manchester Morgue / Don't Open the Window / No Profanar el Sueño de los Muertos / Non si Deve Profanare il Sonno dei Morti / Zombi 3: Da Dove Vieni? (1974) ***½

Let Sleeping Corpses Lie / The Living Dead at Manchester Morgue / Breakfast at the Manchester Morgue / Don't Open the Window / No Profanar el Sueño de los Muertos / Non si Deve Profanare il Sonno dei Morti / Zombi 3: Da Dove Vieni? (1974) ***½

It is well recognized that the great explosion of Italian zombie movies was a consequence of the remarkable European success of Dawn of the Dead. But although it was the first one out of the gate in that massive outpouring, Lucio Fulci’s Zombie, wasn’t quite the first Romero-inspired zombie movie to be made by an Italian studio. Five years earlier, when the only modern zombie flicks on the scene were the original Night of the Living Dead, Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things, and the first two of Amando de Osorio’s Blind Dead movies, the Rome-based studio Cinecitta hired Spanish director Jorge Grau to deliver a film their producers described as “Night of the Living Dead, but in color.” And as with Zombie in 1979, the result of this unabashed cash-in came out vastly better than it had any right to. Let Sleeping Corpses Lie my not be quite the tight little package of gut-munching awesomeness that Zombie is, but it is as good as its title! (And no, I’m not talking about one of those lame titles further down the list, either!)

We begin with one of the wackier credits sequences I’ve seen lately. While a young hippy art dealer named George (Ray Lovelock, from Autopsy and Last House on the Beach) closes down his store in London for the weekend and hops on his motorbike, all kinds of strange shit goes on around him. Pollution and its effects are everywhere. Small, dead animals litter the streets. Half of the people he drives past are wearing some kind of bandana or facemask over their mouths in an effort to keep out the smog. And at one point, for no apparent reason, a woman in sunglasses tosses off her overcoat and dashes, naked, across an intersection. Yep. This is definitely an Italian movie.

George’s destination is a fixer-upper group house out in the country, where he plans on meeting some friends of his. Emphasis on the “plans on.” Those plans fall by the wayside at a gas station, when the ninny in the Mini at the pump in front of him backs up into his motorcycle, and crushes the front wheel. Edna (Christine Galbo, of Riot in a Women’s Prison and What Have You Done to Solange?), as the Mini-driver introduces herself, is suitably apologetic, and even lets herself be talked (or rather, brow-beaten) into giving George a ride to his destination. In fact, since it was her exhaustion from the long drive she’d already made that led her to put her car into reverse rather than first gear, Edna even agrees to let George drive. But as the fork in the road that will commit them either to his destination or to hers nears, Edna regrets her generosity. George is just out for a weekend vacation, but Edna has urgent business to attend to. Though she keeps quiet on the details with her unintended companion, Edna is due at her sister’s place, where she and her brother-in-law, Martin (Jose Lefante, from The Wicked Caresses of Satan and Strange Love of the Vampires), will make arrangements to ship little sister Katie (Jeannine Mestre) off to rehab for her heroin addiction. And while Edna succeeds in convincing George that her errand is more pressing than his, there’s still a major obstacle standing in her way— she’s forgotten how to get to Katie’s house once inside the village where she lives!

You'd think that would be just about the last straw for George. Evidently he’s a more compassionate man than I am, however, for he simply stops the car by the bank of the stream that was the last landmark Edna could remember, and goes to ask for directions— after confiscating Edna’s car keys, that is. Hey, I wouldn’t want put it past the useless little bimbo to drive off and leave me stranded in the boonies, either! Crossing the creek on a trail of stepping stones and cresting the hill on the other side, George encounters a farmer who is meeting with two men from the Department of Agriculture. They’ve got a new pest-control gizmo, some kind of ultrasonic contraption, that they’re trying to convince the farmer to adopt as an alternative to chemical pesticides. Now I personally would have expected any good hippy to embrace such an idea, but George is just as suspicious of the machine as he would be of an advanced new poison. Be that as it may, the farmer is able to find enough gaps in the ensuing argument to tell George how to reach the home of Edna’s sister. But while the two of them are conferring, Edna is attacked in the car by a hulking, bearded man (Fernando Hilbeck, of Flesh & Blood and The Possessed) whose labored breathing sounds alarmingly like a death rattle, in a scene that bears no little resemblance to the cemetery incident in Night of the Living Dead. Edna is faster than her assailant, however (even in stiletto-heeled go-go boots), and she reaches George and the farmer with plenty of time to spare. In fact, the bearded man is nowhere to be seen when she breathlessly reports the attack. The farmer mentions that Edna’s description of the vanished man sounds an awful lot like “Guthrie the Loony.” The trouble with that identification is that Guthrie drowned fully a week ago.

It is indeed Guthrie, though, and menacing motorists by the riverbank doesn’t begin to exhaust the mischief the zombie tramp is about to get up to. An hour or so later, after sunset, he shows up at Katie’s house while her photographer husband is out taking nighttime shots of a nearby waterfall. Figuring Martin’s absence gives her a perfect opportunity to shoot up, Katie sneaks out to the tool shed. But Guthrie is there waiting for her, and he’s no friendlier to Katie than he was to her sister. Zombie Guthrie chases Katie all the way to the waterfall, where he kills Martin, and then chases the woman some more. The only thing that stops him from catching her is the coincidental arrival of George and Edna on exactly the right stretch of road at exactly the right time. Zombies must not like bright, artificial light, because Guthrie ducks back into the woods and withdraws the minute he sees the glare of the Mini’s headlamps.

Normally, calling the cops is exactly what you’re supposed to do in a situation like Edna’s, but this time, that ends up being the worst choice she could possibly have made. The local detective sergeant (Arthur Kennedy, from Fantastic Voyage and Taboo Island) immediately decides that Katie killed Martin herself (nevermind that the man’s ribcage was stove in by somebody far stronger than any sickly, female junkie), and that Edna is only claiming to have seen the man Katie describes as the killer in order to help keep her sister out of prison. As for George, the sergeant just doesn’t like him, what with his “long hair and faggot clothes.” Unwilling to listen to either his or Edna’s protestations that George really has nothing whatsoever to do with any of this, the sergeant concludes that he’s a suspect too— even if he doesn’t seem to have any real idea what he suspects him of. You mark my words, the enmity of this two-bit Harry Callaghan is going to cause George and Edna even more trouble than the zombies.

And yes, that should indeed be plural. While the cops are digging for dirt on them, George and Edna launch a little investigation of their own. At the hospital to which Katie has been committed on the sergeant’s orders, George meets a doctor named Duffield (Vicente Vega), who seems to be just about the only person in town who doesn't instantly distrust him on principle. The doctor is in the midst of dealing with an extraordinarily odd crisis— the babies in the nursery ward have gone berserk, and have begun biting and gouging the nurses whenever they try to touch them. When George wonders aloud whether that ultrasound device the Department of Agriculture is testing nearby could have anything to do with it, Duffield takes the possibility seriously enough to want to have a look for himself. What the Department of Agriculture guys tell Duffield is worrisome indeed. The machine works by attacking the insect nervous system; turn it on, and every bug for a mile around flips out and starts killing everything it can find. After a little while, the insects have all destroyed each other, and voila!— consider all pests controlled. And as the men point out, if the machine had any effect on humans, the two of them would have killed each other long ago. There’s one thing the doctor grasps immediately that the agricultural researchers don’t, though. Babies’ nervous systems aren’t fully formed. In their primitive, unfinished state, might they not be susceptible to the machine’s influence? And, more to the point for the rest of the movie, if that's true, then what about corpses? Could a dead, decayed nervous system become simple enough for the machine to work its special magic on it, too? George and Edna will soon be learning that the answer to that question is an emphatic “yes,” and that Guthrie isn’t the only dead guy roaming around in the Manchester hinterland.

A word of caution concerning Let Sleeping Corpses Lie: the first hour of this movie is extremely slow-moving, constructed more as a mystery than as an out-and-out horror film. Guthrie is the only zombie in town for much of the running time, and he stays mostly out of sight except to set up the two Londoners’ troubles with the law. But once George and Edna’s investigations take them to the cemetery where Guthrie was supposedly buried, only to find his empty coffin and the mangled body of the sexton, the movie shifts into a higher gear. The methodical first and second acts are necessary, however, to establish the film’s most intriguing and distinctive feature, the protagonists’ dual struggles against the zombies on the one hand and the willfully blind detective who blames the couple from out of town for the violence committed by the undead on the other. Let Sleeping Corpses Lie is as paranoically anti-authoritarian as any movie George Romero has made, and is more relentlessly downbeat than many of them. It also anticipates a wrinkle Romero added very late in his own zombie cycle, the evil human who gets his comeuppance from the zombies. But the form that idea takes here is ever so much more satisfying than what happens during the closing phase of Day of the Dead. Let Sleeping Corpses Lie also has the distinction of being probably the most scenically beautiful zombie movie I’ve ever seen. Like Tombs of the Blind Dead, it makes the countryside in which it is set as much a character as any of the people wandering around in it, although the specific ambience that countryside creates is, of course, very different. Visually, Let Sleeping Corpses Lie comes across less as “Night of the Living Dead, but in color” than as “Plague of the Zombies, but with gut-munching.” Modern audiences might demand a little bit more gut-munching, I suppose, but I’m quite happy with Let Sleeping Corpses Lie just the way it is.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact