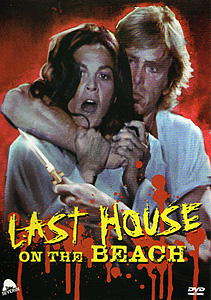

Last House on the Beach/Terror/La Settima Donna (1978) **

Last House on the Beach/Terror/La Settima Donna (1978) **

We all realize by now that the Italians would rip-off any damn thing at all, provided it turned a certain amount of profit. We also realize that these Italian rip-offs, 97 times out of a hundred, are fucking terrible, even when they were inspired by something as great as The Road Warrior or The Exorcist. So now ponder for a moment what the average result is going to look like when the model being copied is a turkey like The Last House on the Left.

Okay, I’m sorry— that was a trick thought-experiment. Actually, so far as I’ve seen, the Italian Last House clones tend to be slightly more effective than the real thing, although the reason why says at least as much about what Wes Craven did wrong as it does about what his imitators might have done right. Simply put, large segments of Italy’s commercial film industry had become so brutal and sleazy and stupid by the mid-1970’s that it may never have occurred to the makers of movies like Hitch Hike and Night Train Murders just what an affront against decency Craven’s film was intended to be. I mean, when you’ve got mouth-breathers like Luigi Batzella building an entire genre on the foundation of Love Camp Seven, and Gualtiero Jiacopetti and Franco Prosperi running off to Haiti to shoot Goodbye, Uncle Tom with the full cooperation of the monstrous Papa Doc Duvalier, how transgressive can Krug Stillo and his accomplices possibly look? The central failing of The Last House on the Left was Craven’s inability, in practice, to maintain the unflinching attitude toward the villains’ crimes that was his stated aim; Craven was as thoroughly unmanned by what he was creating as he meant the audience to be, and he insulted all concerned— himself, his viewers, his collaborators, the characters in his story— by seeking refuge in the crudest and most contemptible form of comic relief. The Italians, on the other hand, had sunk too low already to be intimidated by two measly rape-murders. From their point of view, The Last House on the Left was just one more lucrative target for exploitation by duplication, with the paradoxical result that the copies, although made without more than the tiniest trace amounts of creative ambition, often achieved by accident the horrific clarity of purpose that their model lacked. A House on the Edge of the Park or Last House on the Beach might fall flat for other reasons, but directors who allowed themselves to be stared down by their own bad guys would generally not be among their faults.

The baddies in Last House on the Beach are a trio of bank robbers called Aldo (Ray Lovelock, from Queens of Evil and Let Sleeping Corpses Lie), Walter (A Spiral of Mist’s Flavio Andreini), and Nino (Yeti: Giant of the 20th Century’s Stefano Cedrati). The heist that opens the film seems to be going exactly according to plan, so we’ll have to consider it a tremendous lapse of criminal professionalism when one of the robbers gratuitously sprays the tellers’ desks with bullets on their way out the door, then guns down a hostage while making the final getaway. (Note that all of the shots in this scene are composed so as to place the robbers’ faces outside the frame. It plays like an annoying affectation at the time, but it sets up the one genuinely interesting thing director Franco Prosperi does in the whole film, so I’m willing to grant it special dispensation.) With the aforementioned pointless shooting greatly increasing the interest of the local police in catching them, it’s rather unfortunate for Aldo and his boys that their getaway car is a rattletrap Citroen that even Montgomery Scott would be hard-pressed to keep on the road. When the car suffers what threatens to be its final crap-out, the fugitives are right in front of— you guessed it— a huge villa overlooking a secluded stretch of beach. (Four out of five Italian crime-movie villains surveyed say there’s no better place to hide out when you’re on the lam after an unnecessarily vicious bit of wrongdoing!) Not only that— and how’s this for excitement, eh?— that villa is occupied at the moment by five barely-legal female art students studying for their college entrance exams, and chaperoned by a woman (Florinda Bolkan, of Flavia the Heretic and Don’t Torture a Duckling) who, though somewhat dour and roughly of age to be her charges’ mother, isn’t too much less of a looker herself. If you’ve seen any movie with the words “House on” in the title somewhere, you know exactly how Aldo and his buddies are going to amuse themselves while they wait for the manhunt to move on ahead of them and for Aldo himself to resurrect their car.

Inevitably, however, there are complications. To begin with, Nino— the biggest psycho and the dimmest bulb of the bunch— drastically compromises the gang’s mobility when he makes the opening rape attempt on Eliza (Sherry Buchanan, from Tentacles and What Have They Done to Your Daughters?), and she gives twice as good as she gets. Nino winds up with a nasty shiv-wound in his hip-socket, and only by killing the villa maid (Trauma’s Isabel Pisano) are the criminals able to regain control of the situation. Now the robbers’ time of departure will be set not by the readiness of the car or by the emergence of a chance to slip through the police dragnet, but rather by the pace at which Nino’s body repairs itself— which won’t be any too fast, if the infection that sets in a couple days later is any indication. On the other hand, the prospect for yet greater entertainment within the villa arises when it comes to light that Christina the chaperone is really Sister Christina, one of the nuns from the girls’ Catholic boarding school. Terrorizing and abusing innocent people is one thing, but terrorizing and abusing a houseful of Catholic schoolgirls and a sexy nun? Now that’s what I call a party! The lads have it all their way for a while, but when Walter and Nino double-team Lucia (Laura Trotter, from City of the Walking Dead and The Story of Piera) while Aldo makes Sister Christina watch, Eliza and Margaret (Luisa Maneri, of The Eleventh Commandment and the Private Lessons that doesn’t star Sylvia Kristel) start taking a more pro-active stance. And when the criminals’ retaliation against those girls’ efforts to free themselves and their companions escalates to lethal levels, Sister Christina decides that there are some times when turning the other cheek is for pussies and suckers.

Last House on the Beach is a mostly unexceptional example of its breed, and the bulk of what little interest it generates (apart from that one feature I’ve hinted at already, and will discuss before much longer) is of an illustrative nature. On the one hand, it gives some idea of how far you can coast in shock cinema on sheer insensitivity to the possibility that you might have something to apologize for, and on the other, it shows quite clearly how such insensitivity acts as its own limiting factor. If you’re only dimly aware that there are lines you aren’t supposed to cross, then it stands to reason that you’ll cross lots of them by complete accident— and since the violation of norms is the whole purpose of this filthy little crawlspace under the horror genre’s floorboards, that kind of mean-spirited cluelessness can pay great dividends in an “at the mercy of psychos” movie. Last House on the Beach doesn’t earn or deserve the tiny bit of power it derives from forcing Sister Christina to choose between her sacred vows and the survival of her students, for neither Franco Prosperi nor any of the movie’s three writers give any indication that they’ve consciously considered that aspect of the conflict, but that tiny bit of power is there nonetheless. But at the same time, nothing in Last House on the Beach matches the impact of the strongest material in The Last House on the Left, simply because that very same obtuseness prevents this movie’s creators from capitalizing on their transgressions in the same calculated, deliberate way. You can break the rules without knowing them, but in order to flout the rules, you have to understand them intimately first. Wes Craven knew exactly what he was doing (or at any rate, exactly what he was trying to do); Prosperi and company evidently knew only that Craven and Sean Cunningham had made a pile of money doing it, and so they went through all the same motions in the hope of making a pile of money, too. Unsurprisingly, their version goes most seriously awry precisely in those places where Craven got it right. You might think that no gang rape scene could possibly miss the mark so far as to stray into unintended comedy, but Lucia’s slow-motion, disco-scored violation, captured from a variety of goofy camera angles and with mugging from Stefano Cedrati that would make even Cash Flag say, “Jesus, man— get a grip, would you?” is here to put that expectation to the test.

Let us go out on a high note, however, with Last House on the Beach’s sole glimmer of honest, independent creativity. Beginning with Craven’s prototype, it has been customary for movies of this sort to include one character among the criminals who is slightly more sympathetic than his companions, one who might almost be expected to turn on the others when the gravity of their crimes finally sinks in. In The Last House on the Left, it was Junior Stillo, the heroin-addicted teenage son of the gang’s leader. In House on the Edge of the Park, it was Ricky, Alex’s borderline-retarded sidekick, who was just barely capable of grasping the significance of the events at the protagonists’ party. And in Last House on the Beach, it’s Aldo, of all people— or at least that’s what we’re led to believe at first. Aldo may be the ringleader of the robbers, but our first impression is that it’s just a job to him. Walter and Nino are the sadistic psychos, and while there’s certainly a limit to how far Aldo is willing to defend the captives at the villa against them, he does seem to make an effort to reign them in. Aldo is also the only member of the gang who will deal with either Christina or the girls on any level other than terrorizing them, even to the extent of attempting to befriend Margaret in spite of everything. We very quickly come to suspect that Nino was the trigger-happy gunman at the bank (remember, we never got to see anyone’s face during the robbery scene), and during a moment alone with Margaret, Aldo explains that he actually never set foot in the bank at all; he was waiting outside in the getaway car the whole time. But— and this is where Prosperi earns just a little of my respect— we’re made privy to something that Margaret is not during Aldo’s tale. We get a flashback to the heist intercut with the conversation, and every time Aldo tells Margaret anything about the robbery, that flashback shows us that he’s lying. Not only was Aldo not in the car outside, but it was he who both fired on the tellers’ desks and shot the hostage in the ensuing standoff with the security guards. Aldo never changes his demeanor as the “reasonable,” “approachable” member of the gang, but from that moment forward, we know what he really is. I just wish Prosperi had done something with that duality.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact