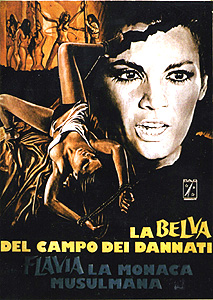

Flavia the Heretic / Flavia the Rebel Nun / Flavia, Priestess of Violence / Flavia / The Heretic / The Rebel Nun / The Muslim Nun / Flavia, la Monaca Musulmana / Flavia la Defroquee (1974) **

Flavia the Heretic / Flavia the Rebel Nun / Flavia, Priestess of Violence / Flavia / The Heretic / The Rebel Nun / The Muslim Nun / Flavia, la Monaca Musulmana / Flavia la Defroquee (1974) **

From the liner notes to the new Synapse DVD edition of Flavia the Heretic: “Call Flavia the Heretic what you will... a bold statement on feminism and female independence or just one of the goriest exploitation films ever made.” Hmmm... Can I pick “C. None of the above”? I don’t seem to be having much luck with nunsploitation movies. The Sinful Nuns of St. Valentine was good and all, but I was hoping for a little more ‘sploitation from it. Flavia the Heretic seemed like a sure bet on that score, what with alternate titles like Priestess of Violence and The Muslim Nun. But while it does contain a pair of exceptionally grisly torture scenes, its fair share of nudity, and a decent amount of really weird shit, the payoff from those things just isn’t quite enough to make this pretentious and laboriously paced movie worth the time and effort.

It is the turn of the fifteenth century in what I take to be the south of Italy. There has been a close-fought battle between Christian knights and Turkish corsairs, which ended in victory for the defenders, and on this night, the son and daughter of the leader of those knights have snuck out to the battlefield to have an up-close look at a real Muslim. The great bulk of those remaining on the field are dead, of course, but at least one wounded Turk still lives when Flavia Gaetani (Florinda Bolkan, of A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin and Don’t Torture a Duckling) and her brother arrive on the scene. Flavia finds the Turk fascinating, and more than a little attractive in an illicit sort of way. But before the two of them have a chance for any contact beyond a nervous exchange of smiles, Count Gaetani, the girl’s father, appears— evidently having followed his kids’ path from the castle— and finishes off the last living corsair.

Some time passes, but I’m not at all sure how much. The count has given up on any intentions he might have had of marrying Flavia off, and has committed her instead to a convent. This without any input from Flavia herself, you understand. She naturally makes a most unwilling nun, and unsurprisingly isn’t very good at it. Case in point: The main hall of the convent is decorated with an almost Byzantine-style mosaic depicting St. George brandishing his sword and shield, presumably in a gesture of protection over the women of the convent. Flavia invariably keeps her eyes glued to the mosaic during her daily prayers, but not for the reasons her abbess might think. As she will later confess to one of her fellow nuns, to her the icon isn’t St. George, but rather the strapping Muslim warrior she saw lying on the battlefield that night. Virginal though she may be, Flavia has, as a certain ex-president once put it, lust in her heart. She isn’t the only horny novice, either. One day, the convent receives a party of Tarantella pilgrims, and a young nun named Sister Livia (Raika Juri) is so taken in by the sectarians’ ecstatic— and frankly sexual— mysticism that she ends up joining in their rather scandalous observances. This is more than the abbess will tolerate; she has the pilgrims expelled from the convent, and Livia confined pending an examination by the bishop.

This incident is what really gets Flavia thinking about something that’s been bothering her in a vague way ever since she was forced to become a nun. As she explains to Abraham (Claudio Cassinelli, from The Great Alligator and The Scorpion with Two Tails), the convent’s Jewish handyman, when she lived at home, her father’s word was law. Partly that was because he was a count, of course, but it was obvious that the real reason for his unchallenged dominance of the household was his maleness. Now that Flavia is in the convent— an all-female environment— you’d expect it to be different, but it isn’t. The abbess has no power that is not granted her by the bishop, and the church hierarchy of which he is a part consists entirely of men. Hell, even the God in whose name they work is a man! What justice can there be for a woman in a world where men run everything, and their governance is required to go unquestioned? In fact, the more Flavia thinks about this, the more she sees to convince her that the rule of the male is inherently brutal and iniquitous (and the more we see to convince us that the rule of the filmmakers is inherently clumsy and heavy-handed when it comes to making a political point). On her travels about the neighborhood of the convent, she sees the duke who is her father’s liege-lord raping a peasant girl in a pigsty. She witnesses the gelding of a horse, and has it explained to her that only one stallion is needed to service the entire herd of mares. The final straw comes when she learns that the bishop has condemned Livia to death by torture for her participation in the Tarantella pilgrims’ heterodox ritual. She follows the condemnation procession to her father’s castle, where she tries in vain to convince Count Gaetani to give clemency to the prisoner, and where she watches helplessly as the count’s executioners do their work.

Upon returning to the convent, Flavia hatches a daring plan. In company with Abraham, she flees into the countryside, hoping to find safety outside the reach of the church. The escape attempt is a miserable failure, however, and the two fugitives are soon recaptured. Abraham’s punishment is never described, but Flavia is subjected to a prolonged flogging upon her return to the convent. Her efforts to break away have led to one small improvement in her life, however, in that they have brought her to the attention of an older nun named Sister Agatha (Maria Cesares). Agatha is, in her way, even more rebellious than Flavia, but she has the wisdom to keep her opinions to herself when she is within earshot of anyone in authority. It is Agatha’s contention that the entire institution of the Catholic Church exists solely for the purpose of keeping the power of women in check. Because women ultimately control sex, they would naturally dominate men through guile and manipulation, and so men must invent a God that condemns female sexuality as necessarily depraved, as something that must be kept bottled up in places like convents. But if more women came to understand this, then the very walls which were intended to serve as a woman’s prison would become her fortress instead, and Agatha has dedicated her life in the convent not to the service of Christ, but to the furtherance of her secret sexual revolution. In Flavia, she finds a receptive, if also reluctant, acolyte.

What eventually transforms Flavia from a Rebel Nun to a Heretic, and finally to a Priestess of Violence, is an attack by Muslim pirates on a seaside church not far from the convent. Flavia watches as the men of the village— so brave and fearsome when lording it over their wives and daughters at home— flee in panic from the Turks. She watches as the “infidels” rout a contingent of Christian knights who ride to the defense of the church. And finally, she watches as Sister Agatha interferes in the duel between the rapist duke and the Muslim bey (Anthony Higgins, from Vampire Circus and Taste the Blood of Dracula)— on the side of the bey— and is run through by the duke’s lance. The old nun’s purpose is served, however, for her intervention gives the bey the chance to reclaim the initiative and turn the tables on his opponent. And when Flavia sees the duke being led away in chains by the bey’s men, she experiences a resurgence of the attraction she felt for that other Turkish soldier— the one she associates with the mosaic of St. George in the convent. She willingly offers herself to the bey, realizing that he represents the very thing she fled the convent to find— a place outside the reach of her hated Church. What’s more, his band of raiders represents an opportunity to bring the same freedom to all her sister nuns who remain in church-sanctioned bondage. Flavia tells her new lover all about the convent, and suggests it as the target of his corsairs’ next attack.

Flavia isn’t just a bystander in the assault, either. She rides in at her bey’s side when the Turks storm the convent, and takes an active role in arranging the subsequent debauchery. It is Flavia who administers aphrodisiacs to the nuns, Flavia who smashes the icon of St. George with a morning star, and Flavia who suggests that the captive duke be gelded like the horse in his stables was. Then she and the bey take hallucinogens and make love on the floor of the very chapel where she once knelt each day in insincere prayer. But Flavia is only just getting started. After helping to despoil the convent that so thoroughly despoiled her, she leads her Muslim allies in an attack upon the castle of her own father, clad like an anti-Joan of Arc in the duke’s confiscated armor. Flavia’s success, however, is her own undoing. If she thinks medieval Islam is any more receptive to strong and independent women than its Christian counterpart, then she’s got another thing coming.

Sounds exciting, doesn’t it? Frankly, it ought to be. But director Gianfranco Mingozzi hasn’t got the first clue how to handle an action scene, and so he puts as much space between those as he can get away with, and then bungles them when they finally arrive. The clashes between the bey’s men and the Christian knights are the weakest scenes of the film, looking less like battles than the performances of an inexperienced and underfunded chapter of the Society for Creative Anachronism. Never have I seen so much milling about in a cinematic fight scene. Mingozzi is on surer footing in his exploitation sequences, but again it’s a case of too few and too far between. The only times Flavia the Heretic comes anywhere close to living up to its reputation are in the torture of Livia and in the final fate of its heroine. The Middle Ages had no patience for heretics, and so it’s no surprise to see that Flavia comes to a very bad end. The precise nature of that bad end, on the other hand... well, I can’t say I saw that coming!

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact