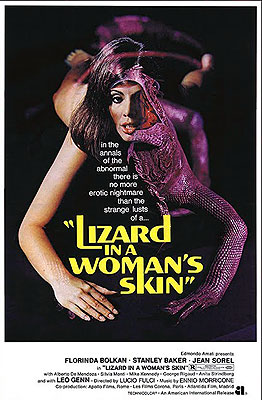

A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin / Schizoid / Una Lucertola con la Pelle di Donna (1971) ***½

A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin / Schizoid / Una Lucertola con la Pelle di Donna (1971) ***½

Like most of his American fans, I expect, the first place my mind goes when I hear Lucio Fulci’s name is to the trio of zombie movies that he made at the turn of the 80’s. That isn’t entirely fair, since those films represent just one brief phase of a long and extremely varied career, but I can’t help it. The zombie triptych were the first Lucio Fulci movies I saw, and two of them remain the ones I love best even now. But with A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin, it isn’t as absurd as it might initially seem to draw a reflexive connection to The Beyond or The Gates of Hell. Remember that what made Fulci’s second and third zombie flicks so distinctive was that they treated the living dead as merely a symptom of a much larger problem. Portals to Hell were standing ajar, and reality itself was coming unglued under Infernal influence. Well, A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin deals with the unreliability of reality as well. It may be a giallo— a murder mystery with the heart of a psycho-horror movie— but the crime at the center of its plot blurs the distinction between dreams and waking life, and the only eyewitnesses were too full of LSD at the time to perceive what they saw in any remotely trustworthy manner.

Carol Hammond (Florida Bolkan, from Olga O’s Strange Story and Last House on the Beach) is the daughter of wealthy and respected London attorney Edmond Brighton (Leo Genn, of Frightmare and The Death Ray of Dr. Mabuse), and the wife of Brighton’s junior partner, Frank Hammond (Jean Sorel, from The Sweet Body of Deborah and Short Night of Glass Dolls). This is evidently Frank’s second marriage, because sharing the Hammonds’ spacious luxury flat with them is a teenaged girl named Joan (Ely Galleani, of Born for Hell and 5 Dolls for an August Moon) who is his daughter, but not Carol’s. Despite all the money and privilege Carol enjoys from birth and marriage alike, she’s a troubled woman, and has been undergoing psychoanalysis for some time. Among her symptoms is an oppressive series of dreams in which she appears as the lover of Julia Durer (Anita Strindberg, from The Case of the Scorpion’s Tail and The Tempter), the libertine who lives in the apartment next door. In her waking life, Carol detests Julia. She considers the other woman’s lifestyle (scarcely a week goes by without Julia having every hippy, beatnik, and unclassifiable weirdo in town over for a raucous, drug-fueled orgy) a scandal and a disgrace. But you shouldn’t need Dr. Kerr (George Rigaud, of Horror Express and Love Brides of the Blood Mummy) to tell you that deep down, Carol’s distaste for Julia’s activities is outweighed by her envy at the freedom and excitement they imply. Unlike Julia, you see, Carol has to care a great deal what the neighbors think. Imagine what it would do to the reputation of Brighton & Hammond, let alone to her father’s budding career in Conservative politics, if she ever got mixed up in any such thing as what goes on next door!

One day at the office, Edmond receives a phone call from someone identifying herself as “Mrs. Smith.” Obviously that can’t be her real name. We don’t get to hear “Mrs. Smith’s” end of the conversation, but evidently it concerns proof that some member of Brighton’s family is having an illicit love affair. Presumably this is the opening gambit of a blackmail plot, but the call cuts off before any demands are made. Understandably wanting to know just how badly exposed his position is, Edmond asks Frank point-blank if he’s cheating on Carol. Hammond huffily denies it, but in point of fact, he’s fucking around with someone whom Brighton actually knows: their secretary, Deborah (Silvia Monti, from Queens of Hell and Master of Love). It’s hard to tell what, if anything, Carol suspects when Frank uses his next business trip out of town to cover a tryst with his mistress, but plainly something new and upsetting is going on in her head. That night, her dreams about Julia Durer take a much darker turn, as their lovemaking ends with Carol stabbing Julia repeatedly with a heavy-duty letter opener. There are witnesses to this dream-murder, too, for looking down from a balcony suspended in seemingly empty space are a pair of hippies with deathly pale skin and blind, unblinking eyes. Dr. Kerr considers Carol’s nightmare a breakthrough when she describes it at her next therapy session. He believes that by symbolically killing the personification of Carol’s unacknowledged, unattainable desires, her subconscious is signaling its readiness to put all that behind her at last.

Several days later, Julia’s cleaning lady notices an appalling stink as she lets herself into the flat, and soon thereafter discovers her employer lying dead of multiple stab wounds. Inspector Corvin of Scotland Yard (Stanley Baker, from Knights of the Round Table and The Hidden Room) is in no position to spot this, of course, but we notice at once that the scene of the crime looks like a more prosaic version of the setting for Carol’s dream, even though she told Dr. Kerr that she’s never set foot in the Durer woman’s apartment. There’s even a mezzanine in the bedroom, with an ornamented balcony overlooking the bed. Also, the cops scouring the place for clues find a fur coat and a silk scarf just like those that were all Carol had been wearing at the start of her erotic nightmare, and the real-world murder weapon is a perfect match for its dream-counterpart. All three items are things Carol actually owns, and which will later be found missing over at the Hammond place. Even the positions of the wounds in Julia’s torso match what Carol dreamed. Inevitably, Corvin and his men question all the neighbors, and thus it is that Carol learns of the sudden, horrifying convergence between her dreaming and waking lives. And when Carol talks her way into being allowed a visit to the crime scene, she too notices everything we have, and faints dead away.

Corvin’s boss, Commissioner McCloud (Basil Dignan, of Naked Evil and Twisted Nerve) takes it as a foregone conclusion that Durer was killed by one of her long-haired dope fiend party guests, but he’s not so securely wedded to his prejudices that he’ll make an ass of himself by, for example, taking the false confession of an obvious loony at face value. After that close call, McCloud sensibly stays out of the inspector’s way for the most part. Corvin is an impressively modern breed of cop for the early 70’s, eager to supplement tried-and-true techniques of crime-solving with input from the scientific squad headed by an officer called Lowell (Black Belly of the Tarantula’s Ezio Marano). It’s Lowell and his high-tech gear that uncover the crucial clue, a pattern of rainwater residue on the victim’s bedroom floor suggesting that whoever killed Julia didn’t come from outside the building. That means the murderer was most likely one of her neighbors. Armed with that information, Corvin sends his men around to collect fingerprints on the sly, making sure that everyone in the building handles their own copy of a glossy photograph depicting a supposed suspect. Lowell then compares the prints taken from the decoy mugshots to those on the murder weapon, and there is indeed a match. It’s Carol, of course.

While the police work on how exactly to go about the delicate business of arresting the daughter of Edmond Brighton on charges of murder, the increasingly agitated Carol makes what might be the most alarming discovery yet. Those zombie hippies in her dream of fucking and killing Julia Durer? They’re a real couple, by the names of Jenny (Penny Brown) and Hubert (Mike Kennedy, from Warriors of the Year 2072 and Cut and Run). Mind you, in the real world, they have normal eyes and nearly normal complexions, but Carol still finds it pretty freaksome to keep running into them on the streets of London wherever young oddballs are found. One day, upon spotting the pair while out on the town with Joan, Carol very nearly works up the nerve to talk to them. They themselves don’t seem to be interested in talking to her, though, when Joan, tired of her stepmother’s bullshit on the subject, barges over to make contact for her. In any case, it really is Corvin that the Brighton-Hammond family should be worried about right now. Although he’s troubled by his inability to attribute any motive to Carol for stabbing her neighbor to death, all the evidence not only points that way, but points that way so forcefully that not even Brighton’s influence can save her by itself. When the arrest inevitably comes, Edmond and Frank go see Dr. Kerr to begin constructing an insanity defense despite Carol’s increasing protestations of innocence. They also take the more drastic step— but a logical one if they really mean what they plan to argue in court later— of committing Carol to a cushy private sanitarium while she awaits trial.

Now maybe Carol really is just a lunatic who committed murder in some kind of fugue state, which her conscious mind retroactively interpreted as a dream. Edmond isn’t so sure, however, notwithstanding his and Frank’s legal strategy on her behalf. While talking to Kerr, Brighton learned that his daughter kept a journal of her dreams as part of her therapy. If someone had access to that journal, they might very well be able to use it somehow to frame her. And as Edmond now knows, thanks to the private detective he put on his son-in-law’s tail after that phone call from “Mrs. Smith” a while back, Frank, who certainly had access to Carol’s dream diary, also arguably has a reason to want her out of the way. What if he’s the one who killed Julia, rigging the crime scene to implicate Carol in order to clear the way for him to take up with Deborah openly? Mind you, neither one of those theories accounts for “Mrs. Smith” herself, and it seems almost certain (to us and Brighton alike) that she must fit into the picture somehow. Jenny and Hubert obviously merit closer attention as well. If Carol’s dream was really a disguised memory, then it follows that the two hippies appeared in it because they really were there, watching her murder Julia. But if the whole business is a frame-up orchestrated by Frank, then they’re probably his accomplices. So what are we to make of it when Hubert sneaks onto the grounds of St. Paul’s Sanitarium to mount what looks like a failed attack on Carol, or when Jenny reaches out to Joan, claiming that Carol didn’t kill Julia, but that Jenny knows who did? Could Jenny have been “Mrs. Smith?” And are she and Hubert acting in concert toward some shared, hidden goal, or do their actions seem at cross purposes to each other because they’ve each got their own agendas? And returning to unestablished first principles for a moment, why the fuck would anyone (except perhaps Carol’s envious subconscious) want to kill Julia Durer in the first place? Was there something we haven’t yet seen going on between her and one or more of the other characters? Rather startlingly for a giallo, there really are halfway plausible answers to all those questions awaiting discovery. And downright shockingly for a giallo, the one person other than the killer who’s looking at all the pieces of the puzzle, whether he realizes it yet or not, is Inspector Corvin.

The Fulciest moment in A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin has very little to do with anything. It occurs while Carol is fleeing from Hubert by retreating ever farther into the depths of St. Paul’s Sanitarium, until, after finally losing him, she ducks into exactly the wrong room. Inside, for who knows what reason, the clinic staff are performing a vivisection experiment in which several small dogs are restrained on some kind of metal rack with their entire torsos split open along the midline to expose all their innards, their hearts pumping, their lungs pulsating, their giblets… I don’t know— gibling? It’s one of the most effective bits of special-effect puppetry Carlo Rambaldi ever devised, and it’s almost heart-stoppingly hideous. Indeed, it was maybe a bit too effective, since it got Fulci brought up on animal cruelty charges— which is a staggering thing to imagine, considering all the atrocious shit that Italian exploitation directors did on film to actual animals from the mid-1960’s through the early 1980’s. Rambaldi reportedly had to bring in the puppets themselves to demonstrate their functioning to the jury! In any case, the inclusion of the vivisection scene demonstrates that Fulci in 1972 was already beginning to think about the horrific potential of pure imagery, untethered to any but the most nominal narrative justification. It’s the same approach that would ultimately yield such unforgettable sights as the underwater fight between a shark and an animate cadaver in Zombie, the beams of light shining through Maria Pia Marsala’s shattered skull in The Beyond, and Daniela Doria literally puking her guts out in The Gates of Hell.

A similar but less revolting effect is visible in the dream sequences during the first act. They provide Fulci with an excuse for the kind of irrational juxtapositions that would make him, in my view, the foremost Italian horror director of the 80’s. What’s especially noteworthy here is that Carol’s dreams are believably nightmarish even without recourse to special effects in the usual sense. It’s all done with editing (as when the scenery changes between cuts from the central corridor of a railroad passenger car to a hallway inside an apartment), camera tricks (strange focal lengths, mismatched lenses, etc.), and set dressing (as in the dream version of Julia’s bedroom, which seems to contain nothing but empty darkness apart from the bed itself and the balcony on which the zombified hippies perch). Although this sort of material largely disappears from the film after Julia is killed, the disorientation that it produces sticks around, and keeps the possibility of Carol’s madness at the forefront of our minds, even as other potential explanations for the crime more in keeping with the traditional concerns of the murder mystery arise to rival it.

But as I’ve already hinted, what’s most remarkable about A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin is that all this overt irrationality sits cheek by jowl— and comfortably, for the most part!— with a detective-story plot that plays unusually fair by giallo standards. Particularly in comparison to the Dario Argento gialli that touched off the explosion of the genre in 1970-1971, A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin is practically classical in its respect for deductive reasoning and the requirements of same. Often you won’t know why something is happening in the moment, but whatever faith you might hold that understandable explanations will eventually come to light generally gets rewarded sooner or later. Most of my favorite gialli are those that tacitly admit their failures as mysteries by emphasizing the killings at the expense of any efforts to solve them, but I’d put this movie forward as an example of the best the genre has to offer in the opposite direction.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact