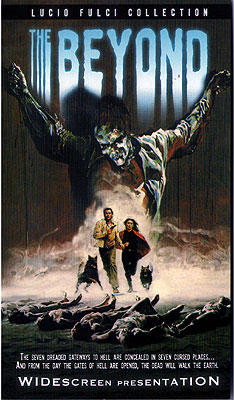

The Beyond / Seven Doors of Death / And You Will Live in Terror: The Afterlife / E Tu Vivrai nel Terrore: L’Aldila / L’Aldila (1981) ****

The Beyond / Seven Doors of Death / And You Will Live in Terror: The Afterlife / E Tu Vivrai nel Terrore: L’Aldila / L’Aldila (1981) ****

As the 1970’s gave way to the 80’s, director Lucio Fulci finally found a way to revitalize his career, which had been stagnating ever since the gialli started losing market share around 1975— he started making zombie movies. The well known Zombie/Zombie 2/Zombie Flesh-Eaters, for all its success both financial and artistic, was a pretty basic take on the subject. No real explanation was ever offered for the resurrection of the hungry dead, and all the movie’s horror stemmed from the simple, unvarnished premise of mildewy corpses clawing their way out of the ground to munch guts. When Fulci made his next zombie flick, The Gates of Hell/City of the Living Dead/Paura nella Citta dei Morti Viventi, he had something a bit more ambitious in mind. Finally turning his attention the question of why the dead would be rising from their graves (and perhaps inspired by the tag-line from Dawn of the Dead’s promo posters: “When there’s no more room in Hell, the dead will walk the Earth”), he came up with the idea of zombies spewing forth from an open gateway to Hell. Then, in 1981, Fulci took another stab at the genre, looking to expand upon his then-unique take on the zombie mythos. The result was The Beyond/Seven Doors of Death/L’Aldila, a movie which just barely fails to equal the standard set by Zombie, and which stands as possibly the best of the many Italian open-portal-to-Hell movies.

In what some observers have called a nod to Corman’s The Haunted Palace, The Beyond opens with a scene set long before the time of its main action. In 1927, somewhere in Louisiana, a mob comes calling at the Seven Doors Hotel. To the inestimable relief of the black man sweating profusely in the hotel lobby, the mob’s business is upstairs, in room 36. These fine, upstanding men are convinced that the occupant of that room, a painter named Schweik (Antoine St. John), is an “ungodly warlock,” and they have come to the Seven Doors to show him what kind of welcome dabblers in the black arts can expect around these parts. After flogging him for a while with iron chains bearing sharpened hooks, the mob hauls Schweik down to the hotel’s basement, where they beat him some more, nail him to the cellar wall (note the biomechanically correct crucifixion!), and melt his face off with quicklime. Then, having made the world safe for... well, I’m sure they thought they were making it safe for something... the posse builds a nice, sturdy brick wall blocking off the part of the basement where Schweik’s battered body hangs. None of the men seems to have noticed Schweik’s protests that he alone could save them from some evil or other that supposedly dwells in the hotel, nor do they pick up on the strange symbol that is carved into the masonry of the hotel’s foundation. But while the mob is hard at work, a young woman not far away is equally busy reading a passage from the Book of Eibon dealing with the “Seven Dreaded Gateways” that are “hidden in seven Cursed Places.” It’s all very mysterious, and it can’t possibly be good news for anyone.

Many years later, in 1981, we begin to get some idea of whom specifically the Prophecies of Eibon won’t be good news for. A woman by the name of Liza Merrill (Catriona MacColl, who’d already been through this once before in The Gates of Hell, and would do so again in The House by the Cemetery) has inherited the Seven Doors, or what’s left of it at any rate. The place is still structurally intact, but it hasn’t been used in years, and has fallen into extreme disrepair. Liza’s got a long way to go before she’ll be able to take advantage of the local tourist trade; not only is the place a wreck on the inside, some of the rooms are locked and their keys irretrievably lost, the roof is in sorry condition, and the basement is flooded. Not only that, Martha and Arthur (Inferno’s Veronica Lazar and Unsane’s Gianpaolo Saccarola, respectively), the seriously weird caretakers, act like they don’t want the place repaired, and one of Liza’s hired workers is gravely injured in a fall from an upstairs window. The last thing the worker says before he loses consciousness is, “The eyes...” It’s a good thing for Liza and the workman that Dr. John McCabe (David Warbeck, from Craze and Razor Blade Smile) makes house calls.

A little while after McCabe comes to collect the injured man, Joe the plumber (Giovanni De Nava, also of The House by the Cemetery) arrives to see about the flooded basement. (In a better world, Joe’s first words to Liza upon seeing the submerged cellar would be, “Well Miss, I think I’ve found your problem... This here hotel is located in Louisiana, so the basement is below sea level. See, that’s why nobody else in this neck of the woods has a basement...”) Joe traces the flooding to a set of pipes protruding from one wall, which he then chisels away in order to get a better look at the offending plumbing, and in doing so, he discovers the part of the basement that was walled off by the mob back in ‘27. He also finds a spot on the wall to which Schweik was crucified where the masonry seems to be dissolving of its own accord, and when he tries to get a closer look at that, he finds Schweik himself, who, despite all the punishment he absorbed 54 years ago, is still in good enough shape to grab Joe by the face and gouge out his eyes. (This is only the first of an unprecedented three eyeball-gougings in The Beyond.)

Martha finds Joe’s body soon thereafter, and Schweik’s as well. (The older of the two stiffs is playing possum when Martha discovers him.) Both corpses are sent to the hospital where McCabe works, and where a colleague of McCabe’s by the name of Harris (Al Cliver, from Zombie and Forever Emmanuelle) hooks Schweik up to what is supposed to be an electroencephalograph, but which is actually an echocardiograph. Harris has no real reason to do this, but it looks really cool when Harris turns his back on Schweik and the machine starts registering a heartbeat, so I’ll let it slide this time. Another thing I’m going to let slide on the grounds that it looks really cool happens just a little while later, when Joe’s wife and daughter come to visit him in the morgue. Wife Maryanne (Laura De Marchi of Flavia the Heretic) comes in first, pointedly ignoring the sign on the morgue’s door that plainly reads “Do Not Entry.” She dresses Joe in his best suit (who can say why), and then sees something and starts screaming. Her screams bring daughter Jill (Maria Pia Marsala) running (she too disregards the “Do Not Entry” sign), and the girl bursts in with just time enough to register the sight of her mother lying unconscious on the floor before the humongous jar of acid on the cabinet above tips over and begins melting Maryanne’s face even more spectacularly than the quicklime melted Schweik’s earlier. Then, as if that weren’t bad enough, the pool of acidic mom-renderings begins pursuing Jill around the room, until the girl is forced to take refuge in one of the morgue’s corpse lockers. The final kick in the ass for Jill comes when she wrests the locker open and finds not only that it is already occupied, but that the corpse inside is (for lack of a better term) alive.

Meanwhile, Liza has been spending much of her time hanging out with a blind girl named Emily (Cinzia Monreale, from Buried Alive and Warriors of the Year 2072), who looks an awful lot like the chick who was reading from the Book of Eibon while Schweik was being lynched. (Not only that, her pus-colored corneas look a hell of a lot like “the eyes...” the sight of which scared Liza’s worker into falling off his scaffold.) Emily seems to know quite a bit about the Seven Doors Hotel, and she is of the opinion that Liza would be best served by getting rid of the place and leaving town. Liza refuses to do anything of the sort, though, even after Emily tells her that the Seven Doors was built over one of the Seven Gateways to Hell. But as it becomes increasingly obvious that reality is breaking down all around her, Liza gradually comes to reconsider her position.

So let’s talk for a bit about reality breaking down, shall we? Not only is there an increasingly large population of increasingly brazen zombies roaming around town, not only does Liza’s interior decorator get his face chewed off by a pack of the noisiest tarantulas since Earth vs. The Spider when he goes to research the ground plan of the Seven Doors at city hall, not only does Liza start seeing the Book of Eibon lying about everywhere she goes, but the house where Emily lives— and where Liza once went to visit her— proves to be a derelict wreck that has lain abandoned for more than 50 years! It only appears habitable when Emily is there and wants the place to look presentable! Why? Because Emily is dead, of course! Not only is she dead, she is apparently a refugee from Hell itself, and it seems that Schweik and his pack of zombies have been sent to the world of the living to bring her back. But even after they accomplish their mission (a zombie seeing-eye dog is involved!), Schweik and his undead posse stick around to set in motion the all-important zombie apocalypse, without which no Italian zombie flick is complete. And true to Italian zombie-movie form, that zombie apocalypse spells trouble for Liza and McCabe, who by the end of the film are just about as royally screwed as any two characters in horror movie history have ever been.

I think the reason why nobody does open-portal-to-Hell flicks quite as well as the Italians is that Italian filmmakers absolutely do not give a fuck whether their movies make narrative sense or not. They seem to start out by making a list of all the wild, hallucinatory horror set-pieces they want to include, and then try to come up with some minimally satisfactory way to string them all together. While such an approach often results in the cinematic equivalent of a migraine headache, in the context of an open-portal-to-Hell movie, it has the salutary effect of creating a sense of cosmic madness, of the sort that the makers of American H. P. Lovecraft adaptations have been trying to achieve for generations without the slightest glimmer of success. This is a subgenre in which bone-deep irrationality and a willful disregard for logic pay tremendous dividends. It is a subgenre which fits Lucio Fulci’s vividly surrealistic imagination like a pair of spandex pants. The Beyond, quite simply, is the movie Fulci was born to make.

Not only that, The Beyond proves once and for all that Fulci was no hack. Granted, you’d never know it from watching Seven Doors of Death, the ineptly executed, pan-and-scan hatchet-job that was until recently the only form in which the English-speaking world knew this movie, but The Beyond is a compositional masterpiece. And the opening sequence set in 1927 is an especially fine piece of work. To begin with, it’s shot in sepia-tint black and white, which has the double effect of enhancing the prologue’s period flavor and displaying Fulci’s mastery of light and shadow in a way that is almost impossible in full color. Note also that this sequence features the only remotely serious attempt at period costume that I know of in a post-1970 Italian horror film. But the most impressive thing about the opening of The Beyond, and the thing that really convinced me of how good a filmmaker Fulci was, is the two-second shot of the black man in the Seven Doors’ lobby. The posse that comes to the hotel is unquestionably a lynch mob from the moment we first lay eyes on its leaders as they paddle across the swamp in a pair of small wooden boats. And significantly, every single member of the mob is white. When the mob enters the lobby, the camera cuts to an extreme close-up on the black man’s eyes; they’re practically bulging from their sockets, and what we can see of his face is soaked with sweat. Then the screen shows us the posse charging up the hotel stairs, and the camera follows them up to room 36, where the real action begins. It’s a complete throwaway, and I had to watch The Beyond twice before its full significance hit me. But that couple of seconds speaks more eloquently about race relations in the American South than all the liberal Hollywood hand-wringing of the past 30 years, and the understatement with which Fulci sneaks it into the first five minutes of a movie about walking corpses and portals to Hell makes the statement even more powerful when it finally catches up to you. So much for the theory that Italian gore movies are all necessarily stupid, huh?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact