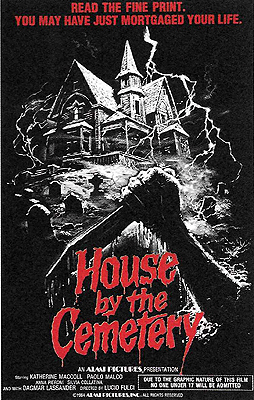

The House by the Cemetery / The House Outside the Cemetery / Zombie Hell House / Quella Villa Accanto al Cimiterio (1981/1984) *

The House by the Cemetery / The House Outside the Cemetery / Zombie Hell House / Quella Villa Accanto al Cimiterio (1981/1984) *

The House by the Cemetery, the first film Lucio Fulci directed after his famous zombie triptych, has nearly as lofty a reputation in cult circles as The Beyond. I canít for the life of me understand why. Of all the Fulci movies Iíve seen, The House by the Cemetery is the most disjointed, most erratically written, hardest to follow, and most thoroughly impregnated with minor annoyances. More importantly, it spends most of its running time (and itís hard to believe this glacially paced film is only 84 minutes long) piling up one mystery after another, but the only one it ever gets around to solving is the least interesting of the bunch, which any halfway with-it viewer will already have figured out independently long before the answer is officially revealed.

We begin, reasonably enough, with a house by a cemetery. A teenage girl is getting dressed in the living room, but the place is obviously untenantedó even my house doesnít have that much dust or cobwebs in it, and Iím just about the laziest housekeeper in the western world. No, whatís happening here is that the girl and her boyfriend have broken in so as to have someplace more private than the back seat of a car in which to have sex. This is no better an idea in The House by the Cemetery than it is in any other horror flick, and both kids are soon killed and dragged down into the cellar by somebody with really nasty-looking hands.

In New York an unspecified length of time later, young Bob Boyle (Giovanni Frezza, from Demons and Manhattan Baby) is staring at a framed photo of the very same house while he should be packing up his toys. Only Bob sees this (the picture changes whenever his mother looks at it), but there's a little girl (The Great Alligatorís Silvia Collatina) in one of the windows, and according to Bob, that girl says itís a bad idea for him and his mother, Lucy (Catriona MacColl, of The Beyond and The Gates of Hell), to accompany Dad on his six-month excursion to the small town of New Whitby, Massachusetts (or ďNew Whitby, Boston,Ē as the caption will amusingly put it a little later on). Lucy, of course, thinks Bob is just imagining things, and tells him to get a move on with his packing.

Well if Lucy really thinks Bob is just making up stories about a girl who says not to go to New Whitby, then why do you think sheís only a little less superstitiously apprehensive about the move than her son is? Truth be told, it is sort of a macabre mission on which Dr. Norman Boyle (Paolo Malco, from The Sinful Nuns of St. Valentine and New York Ripper) is about to embark. Evidently a colleague of his, a certain Dr. Peterson, was up in New Whitby doing some research and cheating on his wife, but killed both his mistress and himself before finishing whatever project he was working on. Boyleís job is to set up shop in the same house that Peterson had rented, figure out the purpose of his research, and then complete it. Incidentally, Iíll tell you right now that Iím at a loss to say just what Boyle is a doctor of. Most of the vague hints we receive seem to suggest that heís in the mental health business, but the research he is being sent to continue is clearly of a historical nature, almost like something out of Lovecraft. Regardless, it is apparent that the topic is of a most sensitive and potentially unnerving nature, for Boyle keeps it scrupulously secret from his wife, whom he evidently doesnít trust not to wig out on him if she knew what he was really up to. And in light of those pretty purple pills Lucy refuses to take, Boyleís assessment probably isn't far from the truth.

Iím sure you already realize this, but the house the Boyles will be renting in New Whitby is the one from the antique photograph in their old apartment, the one where the two teens were murdered in the prologue sequence. Mae, that little girl Bob saw in the photo, is there in New Whitby, too, and she has an odd prophetic vision on the day the Boyle family moves in. She sees a mannequin in a store window lose its head and collapse in a bloody heap on the floor. And as we learn a few minutes later, that mannequin bears a suspicious resemblance to Ann (Ania Pieroni, of Inferno and Unsane), the young woman Dr. Boyle hires as a sitter for his son. I think we know whatís going to become of her.

Now I said before that The House by the Cemetery has more mysteries going than it really knows what to do with, so letís have a look at some of them. The central one, obviously, is the identity of the killer who we may safely assume still dwells in the locked and boarded-up basement of the old house, and what that killer has to do with Dr. Peterson and his research. Then thereís the matter of what caused Peterson to drop what he was supposed to be doing, and begin looking into the history of a surgeon named Jacob Freudstein. (Tell me the truth nowó could you invent a more heavy-handed name for a mad doctor if you tried?) Freudstein was the original owner of the house where the Boyles are staying, and he was interred beneath its living room floor when he died most of a century ago. He had also been expelled from the AMA and banned from practicing medicine in 1879, apparently because of some secret and illegal experiments he had conducted. (And by the way, there seems to have been some kind of communication breakdown among the three screenwriters regarding Dr. Freudstein. The first time his name is mentioned, he is identified as ďJacob Allen Freudstein,Ē but when we see his tombstone later, his middle name has changed to a completely inexplicable ďTess.Ē) We might also ask whoó or wható Bobís friend, Mae, really is, why she is so concerned for his safety, and how she is able to communicate with him in such an exotic paranormal fashion. Furthermore, thereís the strange fact that, despite the doctorís repeated assertions to the contrary, people all over New Whitby are certain that they remember Dr. Boyle coming to visit Peterson at the Freudstein house some time ago, but say that he did so in company with a daughter he doesnít even have. Finally, itís quite clear that Ann the doomed babysitter is in collusion with Boyle on something, and that whatever secret theyíre sharing, it canít possibly be good. For that matter, Ann looks to be in collusion with whomever is down in the cellar, too, and the secrets shared between that pair must be even worse.

The main problem with The House by the Cemetery is that practically all of those plot points will fall by the wayside long before the movieís conclusion, leaving us with no more than an inconclusive clue or two to apply to them. Meanwhile, itís hardly the revelation Fulci and company seem to think it is that the killer in the basement is really Dr. Freudstein, or that he kills in order to prolong his life by unnatural means derived from those nefarious experiments of his. Not only that, what little we do learn about the other strange goings on in New Whitby doesnít add up in a way that makes anything like sense. Itís true that you could say much the same thing about The Beyond or The Gates of Hell, both of which I feel very positively toward. But thereís one important difference between those movies and The House by the Cemetery. Both The Gates of Hell and The Beyond dealt expressly with the supernatural. Iíll accept that reality as I know it has developed a few cracks and tears when there are open portals to Hell lying about, but Iím far less forgiving of gratuitous weirdness in a context where thereís supposedly nothing more out of the ordinary going on than the activities of a Victorian-vintage mad scientist. It isnít just that there are holes in the plotó thatís par for the course with Lucio Fulci. What pushes The House by the Cemetery beyond my tolerances is that Fulci and his co-writers have delivered a script in which they havenít even attempted to fit the disparate parts together. Whereas most Fulci movies feel like heís playing connect the dots with a disordered wish-list of story ideas, The House by the Cemetery plays like he just filmed the dots where they lay, without making even the most cursory effort to form them into a whole. Indeed, The House by the Cemetery hardly seems like a completed movie at all.

Even so, I might have had some mindless fun with this film, but it is presented in such a way that it becomes impossible to avoid trying to take it seriously. The responsible parties obviously thought they were working with Big Ideas (and in fact a number of people whose opinions I generally respect a great deal have somehow managed to mine Big Ideas out of the chaotic disaster that passes for its story), with the result that the movieís tone is much too grave to permit a laugh at its expense. The House by the Cemetery also misses the mark as an exploitation piece, even despite a considerable number of really savage gore scenes. The climactic scene in which Norman and Lucy attempt to force their way into the basement to save Bob from Dr. Freudstein gives an especially clear illustration of how the movie fails in this respect. It looks like Fulci is aiming for nail-biting tension in this scene, as the two adult Boyles wrestle with the door while Freudstein advances up the stairs toward their defenseless son. But Fulci drags it out so long that the sequence falls on its face insteadó there just isnít enough basement to traverse, nor enough stairs to ascend for the zombie doctor not to have reached and dispatched Bob in the time it takes Norman to force the door. And as far as Iím concerned, the bewildering fact that Freudstein sobs continuously in the overdubbed voice of a child even younger than Bob (or some adultís half-assed approximation of such a voice, anyway) completely destroys any scare-power the undead villain might have had. In short, The House by the Cemetery is a ramshackle mess, and I havenít got a clue what so many people see in it.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact