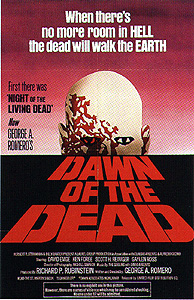

Dawn of the Dead/Zombies (1978) ****

Dawn of the Dead/Zombies (1978) ****

The motivation behind most sequels is obviously commercial. Movie X hits the theaters and makes a buttload of money, so the producers come back a year or two later hoping to rekindle the magic. This is clearly not the case with George Romero’s zombie trilogy, however. Granted, there was money to be made— a studio with any financial discipline at all would have a hard time taking a bath on a Romero living dead movie— but look at the lag times between entries in the series. Night of the Living Dead came out in 1968, but didn’t see a sequel until fully a decade later. Audiences didn’t have to wait quite as long between Dawn of the Dead/Zombies and Day of the Dead, but a seven-year interval is still an awfully long one for coattail-riding. The only plausible explanation— and also the number-one reason why the second and third films in the series are as good as they are— is that Romero has the combination of class and good sense to wait until he’s thought of something new to say by means of his flesh-eating ghouls before marching them out in front of the camera again. If he had wanted to, he could certainly have followed up Night of the Living Dead in 1969 or 1970 with another exercise in raw, unvarnished, purely visceral horror, but the movies he really did make in the early 70’s suggest that he figured he’d already made his definitive statement in that direction. Perhaps realizing that another zombie movie on the model of Night of the Living Dead would have come perilously close to gut-munching for its own sake, he did There’s Always Vanilla and the unfortunate Season of the Witch instead, and left the hungry undead to the makers of Children Shouldn’t Play With Dead Things and Let Sleeping Corpses Lie. By 1973, though, Romero had developed into an exceptionally incisive social critic. In The Crazies/Codename Trixie, he rebuilt many of the ideas he had previously used in Night of the Living Dead into a viciously cynical, intensely paranoid Vietnam allegory that I don’t think has been equaled to this day. Then in Martin, he used the framework of an extremely revisionist vampire movie to look at the power of a dysfunctional upbringing to distort and destroy an impressionable mind. So what real-world social phenomenon do you suppose would best lend itself to examination through the prism of a horde of mindless, undead eating machines? How about the mall?

That’s right. The mall. Romero takes on burgeoning American consumerism, and he does it with gut-munching zombies. But first he hits us with what may be the best “fuck the media” scene ever filmed. Francine Parker (Gaylen Ross, from Creepshow and Madman) and her boyfriend, Steven Andrews (David Emge, of Hellmaster and Basket Case 2), work for the news department of WGON-TV in Philadelphia. Fran is some sort of production assistant; Steve flies the station’s helicopter. An unspecified length of time after the events of Night of the Living Dead, WGON and its competitor stations are scrambling to keep on top of the unprecedented story, going to great lengths to outmaneuver each other while they’re at it. Right now, the big development is the evacuation of most of the city, which is complicated not just by the advancing armies of the dead, but by the unwillingness of many citizens to be evacuated. News teams from all over town are thus swarming all of the trouble spots, their station managers wantonly unconcerned for the safety of the men and women whom they’re putting directly in harm’s way for the sake of ratings. Steve and Fran, for their parts, don’t much like the idea of sticking around as the undead close in on WGON headquarters; perhaps it would be one thing if there actually was an audience, but come on— the city’s being evacuated, for fuck’s sake! Steve’s idea is that he and his lady should sneak up to the roof, get onboard that helicopter, and fly to whatever safety can be found.

Meanwhile, one of those trouble spots I mentioned is about to get a whole lot more troublesome. Many of those who refuse to leave town have banded together in their neighborhood church to oppose the evacuation order— by force if necessary. The authorities have sent the SWAT team in to besiege the church, and officers Roger DeMarco (Scott Reiniger from Knightriders) and Peter Washington (Ken Foree, of Sleepstalker: The Sandman’s Last Rites and From Beyond) are part of that encircling force. After as many minutes of futile entreaties as the cops think they can spare (what with that mass of zombies moving in, and all), the SWAT guys take the church by storm. Dozens of dissidents are killed in the ensuing firefight, which degenerates further into an outright free-for-all when the alarmingly large stockpile of corpses down in the basement (evidently this whole situation stems ultimately from the parishioners’ unwillingness to hand over their dead to the unceremonious mass burnings that began when martial law was declared) begin waking up. DeMarco and Washington, neither one of whom figures that gunning down flesh-hungry corpses and the sentimental loved ones who just want to give them a decent burial was quite what they had in mind when they joined the force, ditch the whole ugly scene and run off to see if they can find someplace where life is still sane. The fugitive cops join forces with the runaway reporters when the former intervene to protect the latter from a band of looters up on the TV station’s rooftop helipad. Steven and Francine agree to take them along, grateful for both the company and the firepower.

Flying out over the Pennsylvania countryside, the four get their first taste of just how widespread the zombie phenomenon really is. The backwoods are crawling with the risen dead, and with roving posses of armed rednecks gleefully shooting them down, too. Steve, Fran, Peter, and Roger nearly get themselves killed while gassing up the helicopter at a rural service station in ghoul country, and begin to reevaluate the wisdom of their plan to set up shop in a region of low population density— they’d probably have to go as far as North Dakota before they found a population density low enough to ensure a reasonable standard of safety. While they’re flying around trying to figure out where to go, Steve notices something interesting— one of the new fully enclosed shopping malls that have just begun springing up all over the outlying suburbs. Sure, it and its acres upon acres of parking lot are full of zombies, but the mall has much to recommend it as at least a temporary base of operations. First of all, there’s a helipad on the roof. Second, squatting there would put a nearly infinite supply of food, clothing, weapons, ammunition, and other supplies within easy reach. Third, the office and warehouse space up on the third floor isn’t readily accessible from the public part of the mall, and could be made zombie-proof with relative ease. The more they all think about it, the better the idea sounds, and what started as a brief stop to conserve fuel while deliberating on their next move in comparative safety rapidly turns into something much more involved.

Our four heroes will spend much of the movie slowly reclaiming the mall from the zombies, which Steve and Peter speculate are drawn there because they dimly remember that it was somehow important to them during their lives. The most pressing order of business, after blocking off and disguising the door joining their quarters on the third floor with the rest of the mall, is similarly sealing off the building’s four main entrances; they won’t be able to exterminate the mall’s zombies effectively if new ones can just wander in at their leisure, after all. The strategy the two ex-cops ultimately arrive at is to hotwire four of the delivery trucks that are still parked by the main loading dock, and move them around to obstruct the outside doors. It is during this hazardous operation (getting to the trucks in the first place means running the zombie gantlet in and around the mall) that the first major setback occurs, as Roger is bitten by a zombie while trying to start the last of the trucks. Peter saves him from being eaten on the spot, but both he and Roger have seen enough zombie action on the SWAT team to know that even seemingly minor zombie bites are almost always fatal. Nevertheless, Roger’s spirits remain high, and after his leg is patched up, he is able to spend his last few days among the living helping his companions sweep the mall clean of the undead.

It’s after the last zombie is killed that Romero really starts harping on his main theme. The use of the zombies as metaphors for mindless consumerism in the preceding section of the film is a cheap shot; things get more interesting on the social criticism front when the humans have the mall to themselves. With no jobs to go to and with everything they need to survive there for the taking in the mall’s upstairs warehouse, Peter, Steve, and Fran (Roger doesn’t last long into this phase of the movie) end up spending their days living out what amounts to the ultimate consumerist fantasy. They’ve got the run of the mall, money is no longer an issue, and they have a lot of time to kill. Understandably, the three survivors start helping themselves to the overpriced merchandise downstairs, equipping their lair with TVs, stereos, fancy housewares, extravagant clothes and jewelry. Eventually the novelty wears off, though, and their games become more complicated. Emptying out the cash vaults of the bank on the first floor, they begin “paying” for what they take and gambling with each other for ludicrous stakes. But in the end, all the fun has been mined out of their situation, and the mall starts to feel like what it really was all along— a huge, well upholstered prison, with the thousands of zombies outside acting as the guards.

But a funny thing happens one night. The vanguard of a passing biker gang (whose nomadic lifestyle has suddenly become an enormous adaptive advantage now that the undead are all over the place) notices the helicopter on the roof of the mall. The gang’s leader makes the intuitive leap that there must also be living people inside, and begins making efforts to contact those people via CB radio. Telling Steve, Fran, and Peter that there are only four members of their group, the bikers ask to be let in. Peter is reluctant, suspecting a trap. Despite the fact that he and his companions have grown weary of their material comforts, they react with horror at the prospect that someone else might try to take them, and deny the bikers entry. Then when Peter spies the seemingly endless column of motorcycle headlights from his vantage point on the roof, he and Steve prepare to defend the mall as if they were the undermanned garrison of a medieval castle. But the bikers are too numerous, and quickly breach the makeshift defenses their opponents have erected. They pour into the mall through the loading dock, allowing the zombies to follow, and when that happens, the New Barbarians are in for a real shock. Their battle tactics, designed for the open spaces of the highway and parking lot, are of much less value within the relatively confined environment of the mall, and they find themselves progressively overwhelmed by the living dead. Steve is also killed in the fighting, and when he revives, he instinctively leads his undead brothers and sisters straight to Peter and Fran. This sets up Romero’s final sneaky trick, the unexpected (if also noticeably provisional) survival of the last two living characters.

I think it says something about the difference between an anti-establishment teenager and an anti-establishment adult that I liked Dawn of the Dead a lot better when I was 15 years old. The Empty Pleasures of Consumerism theme seemed far more transgressive when I was in high school, surrounded by a subculture of pervasive materialism more vapid and uncritical than anything that exists in the adult world. If I bitch about the mall today, I’m far more likely to do so from a quasi-socialist, anti-big business perspective than I am to condemn materialism per se. And for precisely that reason, it’s the first act of the movie and the last that I now enjoy the most. The mall trio’s sudden determination to defend their property (for which even they realize they have very little use, and which never really belonged to them in the first place) against the bikers (who fail to realize that the impending collapse of civilization has rendered most of the booty they hope to plunder from the mall useless to them, too) says more about the tragic stupidity into which class war nearly always devolves than virtually any “serious” movie on the subject you could care to name. Meanwhile, the indictment of the media in the opening scene hasn’t lost the tiniest particle of currency in the many years since Dawn of the Dead was shot. It’s enough to make you do a double take at the simplistic, facile “materialism bad” message of the film’s midsection to see it bracketed by social critiques of such vastly greater sophistication.

The other place where Romero falters a bit in Dawn of the Dead is in his treatment of the zombies themselves. With Tom Savini on board, he has the means to make his zombies far more convincing— and thus far more threatening— than he had back in 1968. And yet despite its increased gruesomeness, this movie ends up being much less horrifying than its predecessor. The reason for this is that Romero’s use of the zombies as a stand-in for the crowds of bleary-eyed shoppers that American ideologues like to imagine throng the nation’s malls each day in a desperate and futile pursuit of happiness through material goods requires that they be made to seem pathetic, pitiable. Because it’s next to impossible to fear something and pity it at the same time, these zombies can’t pack the same punch as the ones in Night of the Living Dead, at least not once the setting has shifted from the apocalyptic warzone of downtown Pittsburgh. There’s still so much right with this movie in the first 40 minutes and the last 15 that I can’t call it anything less than a full-fledged classic, but all the same, Dawn of the Dead now leaves me thinking, “Damn it, George— I know you had a better movie in you than this!”

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact