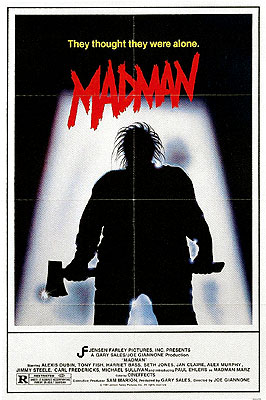

Madman (1980/1981) **½

Madman (1980/1981) **½

If you went to summer camp in New York or New Jersey at any time within living memory, you probably don’t need me to tell you about Cropsey. If you didn’t, you’re probably asking, “Who the fuck is Cropsey?” right now. Cropsey is a legendary serial killer reputed to haunt just about every stretch of woodland where kids from New York can be found camping during the summer, and who has supposedly done so since roughly the dawn of institutional summer camps for children at the turn of the last century. The origin of the legend is apparently forgotten— although the name “Cropsey” itself might be taken to imply the Hudson Valley as its geographic starting point, since that surname is attested in family records there as far back as colonial times. Wherever it came from, the story mutated a lot as it spread out across the Mid-Atlantic region, with each new teller adding details relevant to their own time and place. There are probably scores if not hundreds of variants by now, although the ones I’ve been able to dig up via the internet sort fairly comfortably into about five major categories.

One of those is clearly an outlier, explicitly invoking the supernatural while the rest content themselves with mundane madness and revenge. Stories in this family make Cropsey the resentful ghost of a child who died while at summer camp, whether by accident, suicide, or foul play. The dead camper’s cabin-mates (who, depending on the variant, may be directly implicated in Cropsey’s demise) are said to have hidden his body under the floorboards directly beneath his bunk, which inevitably becomes the focal point of the haunting. There’s a touch of Bloody Mary to this strain of Cropsey stories, too, in that chanting the ghost’s name while lying in the tainted bunk is often supposed to call down his wrath upon anyone foolish enough to do that.

Meanwhile, on Staten Island, Cropsey has apparently merged with the villain of a different urban legend, the ubiquitous hook-handed escapee from a lunatic asylum. Perhaps that’s because Staten Island had the ruins of Seaview Hospital to serve as the killer’s lair, and as a place to which he could abscond with his juvenile victims. This is the version best attested online today, thanks to a 2009 documentary called Cropsey, which plays up the eerie similarities between Staten Island’s corpus of Cropsey lore and the criminal career of real-life child-killer Andre Rand. It too is something of an outlier, though, thanks to its urban (or at least suburban) setting.

The funny thing about the three “mainstream” varieties of Cropsey legend is that you might halfway recognize them even if the killer’s name means nothing to you. In one of them, Cropsey was a pillar of his small, isolated community before a bunch of nitwits at the nearby summer camp accidentally got his son killed. Maddened by grief and thirsting for revenge, Cropsey now launches retributive rampages of murder against campers on the anniversary of his son’s death. In another, Cropsey was himself employed at a summer camp, working as a handyman or caretaker or some such thing, and his turn to insanity and violence was provoked when he burned nearly to death due to a prank gone wrong. And in the third, Cropsey was a reclusive farmer who just went inexplicably berserk one day, and chopped up his whole family with an axe. If you’re a fan of early-80’s slasher movies, every one of those premises should give you at least a mild case of déjà vu. Gender-flip the killer in the “avenging the son” variant, and you get Friday the 13th, don’t you? And come to think of it, isn’t Camp Crystal Lake even implied to be in the Hudson Valley somewhere? The charbroiled caretaker version, meanwhile, literally is The Burning— and that movie actually uses the Cropsey name, albeit with a slightly different spelling. And that last one, with the axe-murdering farmer? That’s Madman.

Like The Burning, Madman was originally supposed to be an overt Cropsey movie. At some early point during production, however, writer/producer Gary Sales and writer/director Joe Giannone learned that Bob and Harvey Weinstein had got the drop on them by just the slightest bit. Madman’s Cropsey character was thus rechristened “Madman Marz,” and the script was tweaked here and there to distance it a bit from its inspiration. And since it happened that the rival productions were working from different versions of the Cropsey legend to begin with, even such minor tinkering was enough to differentiate Madman from The Burning as much as any two summer camp slasher flicks can be said to differ from each other. Indeed, the completed films are sufficiently distinct that I never understood how they could have grown out of the same material until I took it upon myself to dig into the legend of Cropsey, and discovered thereby how remarkably variable the story was.

It’s nearing the end of camping season, and Max (Carl Fredericks— aka Frederick Neumann), the grizzled old weirdo who runs whatever camp this is supposed to be, is growing a bit lax with counselors and campers alike. Perhaps that explains the minor but conspicuous breaches of discipline that occur during a campfire storytelling session one Friday night. First lead counselor T.P. (Tony Fish) takes the entertainment a step too far, singing a murder ballad that genuinely traumatizes some of the younger kids. Then Richie (Jimmy Steele— aka Tom Candella), the oldest of the male campers, greets Max’s own story about Madman Marz with open derision culminating in an act of petty vandalism. Marz is the homicidally loony hermit who legendarily lives in a ruined house a stone’s throw (literally, as we’re about to see) from the spot where Max and company have lit their fire, and he’s supposed to attack anyone who dares to speak his name above a whisper. When Richie hears that, he begins hollering taunts at Marz, and lobs a rock through the decaying house’s last intact window. That’s enough to make Max pull the plug on the outing (although he’s enough of a showman to bring his yarn to a close first), after which the kids all form up to march back to the cabins.

A funny thing happens during that march, though. Richie, last in the boys’ line, is sure he glimpses a man watching him and his fellows from the crotch of a massive tree. Surely not Madman Marz? Evidently Richie’s bravado at the campfire was no front, either, because rather than freaking out like I was expecting him to, the lad detaches himself from marching order, and sneaks off to investigate. Richie loses track of the prowler in the darkness of the canopy, at which point he pursues the next-best lead, and circles back to the supposed Marz house. The boy spends the whole rest of the night snooping around in there— which ironically makes him much safer than his friends who went on to the campground proper. Marz (Paul Ehlers) evidently neither knows nor cares which interloper is to blame for disturbing his hermitage, and he’s going after the whole lot of them.

The first to feel the wrath of Madman Marz is Dippy the cook (Michael Sullivan, of Gums and The Carhops). He’s just finished shutting down the mess hall when the maniac comes to exact his legendary vengeance, so Dippy’s absence will go totally unnoticed later. As for Richie, he isn’t initially missed, either, because his cabin-mates cover for him on the theory that he’s just slipped away to look for a bit of recreational trouble. It isn’t until Max goes home for the night, leaving T.P. in charge, that the other boys become sufficiently concerned to come clean. T.P. rather rashly goes out alone in search of Richie, and finds Marz instead. Another counselor by the name of Dave (Seth Jones) meets the same fate when he goes looking for T.P. Next comes Dave’s girlfriend, Stacy (Harriet Bass), who at least has the good sense to conduct her search from the camp’s 4x4 pickup instead of blundering about on foot. Unfortunately, that truck is a piece of shit prone to not starting for no apparent reason, and it inevitably fails her when she needs it most. That leaves just three counselors: the couple Bill (Alex Murphy) and Ellie (Jan Claire), and T.P.’s maybe-sort-of girlfriend, Betsy (Gaylen Ross, from Dawn of the Dead and Creepshow). Betsy, the closest thing to a Final Girl we have in this movie, is prudent enough to flip the script at this point; she’ll stay at the camp to keep an eye on the kids, while Ellie and Bill go to track down Richie and the missing counselors together. Of course, you probably don’t need me to tell you how well that works. Betsy commendably keeps her mind on the children even when Marz returns to lay siege to the camp, sending them off to whatever safety they can find in the bus they presumably rode in aboard while she takes the fight to the killer.

The moment Madman cropped up on the bill for this year’s April Ghouls Monster-Rama, I knew that I was going to be the only member of my usual drive-in-going group to get anything out of it whatsoever. I can’t say I blame the rest of the gang, either, because it truly does take a slasher aficionado to spot what makes this movie interesting. To the casual viewer, it’s almost certain to look like nothing more than a quickie knockoff of Friday the 13th with an even thinner script and two or three times as much aimless wandering through the woods at night. And it is that, truth be told. Furthermore, a lot of what the practiced eye will notice seems unlikely to score Madman very many points with viewers who don’t already have nigh-limitless patience for cheaply made movies about loonies with knives. For instance, those who have never squinted and strained through the likes of Humongous might not even realize how rare it is for a low-budget film of this vintage that takes place almost entirely in the dark to have such crisp, intelligible cinematography. Madman may offer little in the way of memorable imagery (and it plays its best trick in that department disappointingly early on), but at no point are we left alone to guess what the hell is happening behind a barrier of impenetrable murk. I’d be on slightly firmer ground, I expect, praising the character design for Madman Marz, or the authentic grubbiness of his woodland hideout. Rarely has mere unkemptness and poor personal hygiene looked so threatening. Digging a bit deeper now, notice that Madman is one of the few slasher movies that put children at the killer-imperiled summer camp along with the usual irresponsible adolescents and post-adolescents. I was also impressed by the believability of Madman’s method for separating said adolescents into readily slashable units. Everything hinges on Richie being too curious for his own good; once he’s sequestered at the Marz house, practically everyone who gets whacked meets their end while searching for him. And notice that only after Max departs the campground do the counselors start acting like reckless dumbasses— beginning with the one to whom Max explicitly delegated his authority. Max would have had the wisdom and experience to organize a proper search party when Richie’s absence came to light, but he wasn’t there.

That brings me to the greatest but most easily missed of Madman’s virtues. It isn’t for nothing that summer camps have a tradition of telling horror stories in which kids meet atrocious fates by doing shit they’re not supposed to. Subtextually, these tales are reminders that the woods are a hostile environment, and that whatever survival skills you may have mastered for the city or the suburbs will not help you there one bit. If you don’t want to get eaten by bears or crushed by a collapsing deadfall or poisoned by the wrong goddamned mushroom, then you need to listen to people who know what they’re doing in the wilderness— people like (at least in theory) the staff of the campground. Madman puts the burden of bad judgment on the counselors more than the campers, but the subliminal message is the same nevertheless. First by doing exactly what he was told was sure to piss off Madman Marz, and then by straying from the group without telling anyone what he’s doing, Richie exposes everybody at the camp to avoidable danger. And by disregarding correct woodland search-and-rescue practice, T.P. and the other counselors seal their own doom. Madman, in other words, is faithful not only to its particular strain of the Cropsey legend, but to the hidden agenda of the wilderness scare story genre as a whole. That puts it a little off to the side from the typical slasher movie, in which the cautionary subtext is all about suburban concerns like casual sex, underage drinking, recreational drug use, and social maladjustment. You might notice that it also complicates the job of anyone attempting to give this film a reactionary moral reading. The good behavior that Betsy models plainly has nothing to do with rejecting the allure of hedonism (good Lord, she and T.P. have a hot tub scene together!), and everything to do with keeping her head in a crisis. I tend to think that’s a better interpretation of the slasher subgenre, anyway, but it’s nice to see a movie make it so close to explicit.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact