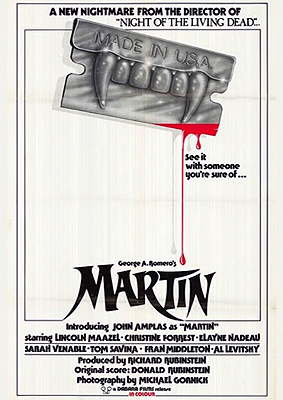

Martin (1977) *****

Martin (1977) *****

The last time we crossed paths with George Romero around here, I got to cover my favorite among his films— which is not one of those that people usually pick. Now we’re going to look at George Romero’s favorite George Romero movie, which isn’t one that people usually pick, either. Martin has always been kind of a difficult movie to see. It never enjoyed the sort of wide theatrical distribution that the zombie series got, nor was it ever a cable TV staple, and it keeps falling out of print on home video. To some extent I can understand that, as Martin isn’t at all what most fans of horror films want or expect from the genre. It has the placid pace, mundane setting, and minor emotional key of a New Hollywood slice-of-life drama— and indeed it gives every indication of being one of those, so long as no one is actively murdering anyone. Furthermore, Martin bridges two subgenres that have historically been denigrated by each other’s fans, operating as both an extremely revisionist vampire movie and a very eccentric psycho-killer film. Even Romero aficionados specifically are likely to be taken somewhat aback, wondering what became of his usual incisive condemnation of American institutions of social control. Look more closely, however, and you’ll see that Martin shows Romero taking to heart the old Second Wave Feminist motto that the personal is political, even though the movie has nothing to say about Feminism as such. What I mean, rather, is that Martin’s target is the oldest and most intimate of all institutions of social control, the family.

On an eastbound overnight train from Indianapolis, two passengers are about to meet up in the most horrid and terrible way. One of them is a woman whose name we’ll never learn (Francine Middleton, of The Love-Thrill Murders), on her way to New York City. The other is Martin Madahas (John Amplas, from Knightriders and Toxic Zombies), a youth of Hungarian extraction traveling to Pittsburgh to take up residence with cousins he’s never met. Martin is also plainly stalking New York Gal, gathering such intelligence on her as which compartment is hers, whether she’s traveling alone, and so forth. Finally, at what looks like about 1:00 in the morning, he picks the lock on her cabin (he has special tools for the purpose, so this is obviously a regular thing for him), and enters armed with a syringe and a razor blade. Martin wasn’t expecting his prey to be awake at this hour, and she puts up quite a struggle even after he injects her with the contents of the hypo. New York Gal does eventually lose consciousness, however, at which point Martin undresses both her and himself, and climbs into bed with her. He doesn’t exactly rape her, though, even if there’s plainly a sexual aspect to the crime. Instead, he arranges the woman’s unconscious, nude body on top of him, slashes her left wrist with the razor, and gulps down the blood that pours forth from her arteries. Finally, Martin cleans himself up, and arranges the victim’s compartment to make her death look like suicide.

Martin is greeted at the train station in Pittsburgh by an elderly gentleman who resembles a Midwestern bohunk Colonel Sanders (Lincoln Maazel). This is Tada Cuda, the cousin who has taken on the responsibility of hosting him for the foreseeable future at his duplex in the nearby township of Braddock. Just the same, Cuda doesn’t seem to like Martin very much, and much of what he says to the lad on the second, shorter train ride out of the city consists of a long list of things that Martin will not be allowed to do. This is because Cuda knows what Martin is— or at least he says he does. You see, Cuda isn’t just talking about his young cousin being a pervert and a serial killer. To hear the old man tell it, Martin is literally a vampire.

It’s all laid out in a set of albums and diaries which Tada brought with him from the Old Country however long ago that was. Supposedly, the Cuda family has been cursed nine times with vampire offspring, of which three are currently surviving. Care and guard over the nosferatu Cudas is a responsibility which the family elders apparently pass back and forth among themselves, and although Tada would never think of shirking the burden now that it has devolved upon him, he also has ideas of his own about how best to carry it. His first priority shall be to secure Martin’s salvation through the Holy Mother Church, but once the boy’s soul is seen to, it’ll be the stake for him at long last. Not surprisingly, Martin himself takes issue with Tada’s reading of his situation— but not with regard to the central fact of his vampirism. No, what Martin objects to is all the cheesy Old Country superstition in which Cuda insists upon cloaking their relationship, all the bullshit about mirrors and garlic and crucifixes. There’s no magic, Martin repeatedly insists. He’s just sick, that’s all. Sick in a way which has enabled him to live 84 years without aging 20, and which periodically requires him to consume large amounts of human blood, but sick nevertheless.

Tada Cuda hadn’t lived alone, even before Martin settled into the garret. Also in the house is Tada’s post-adolescent granddaughter, Christina (Christine Forrest, from Two Evil Eyes and The Dark Half, who would become Christine Romero in 1981). Christina and her granddad have a strained relationship, in a way that anyone from a small-town, Rust Belt family with immigrant elders would probably recognize. It’s just that the “outmoded” Old Country ways that she rejects include the family tradition of the Cuda curse, and the attendant expectation that the clan patriarchs take turns keeping the undead cousins in line. All her life, she’s thought the old man was out of his fucking mind, and she’s both heartbroken and horrified to discover that Martin accepts as much of the family lore about him as he does. Christina does her damnedest to befriend Martin, and to break what she sees as the positive feedback loop of delusion between him and her grandfather. In the end, though, she is forced to recognize that nothing short of a good, long stay in a mental hospital will help either of them. She finally flees Braddock in search of more opportunity and less madness with her slightly hoody boyfriend, Arthur (Tom Savini, of The Ripper and From Dusk Till Dawn).

Christina does institute one clear improvement in Martin’s life, however; she gets him a telephone in his bedroom. At first it looks like even that is a futile gesture, since it isn’t as though Martin has any friends left behind in Indiana. There’s a talk show, though, on the local AM radio station— the old-fashioned kind, driven more by audience call-ins than by ranting hosts— and Martin finds a kind of acceptance that he’s never known in his life as one of Barry the all-night DJ’s regular callers. Barry (the voice of cinematographer Mike Gornick) dubs him “the Count,” and is more than happy to let this kid who says he’s a vampire tie up the phone lines at the station night after night. The audience loves the Count, too, so that he becomes a frequent topic of conversation over the airwaves even when Martin isn’t on the phone with Barry. All those rapt listeners give Martin something that no psychiatrist ever could. By taking his claims of vampirism at face value, even if only on a provisional, thought-experiment basis, they give him the freedom and the confidence to begin talking out his quite considerable list of more conventional emotional problems.

And that brings us to Mrs. Santini (Elyane Nadeau). No relative of Tada Cuda is going to stay under his roof without working, even if he is nosferatu. Consequently, Martin takes a regular position at his cousin’s store as a bagger and delivery boy, while simultaneously hustling around Braddock in search of handyman gigs. One day while making a delivery, Martin meets the lady of the house, a young, sad-eyed, moderately pretty woman trapped in a shit marriage which she lacks the courage to escape anyway. Martin, being not much of a talker under most circumstances, comes across as a good listener— and that’s exactly what Mrs. Santini needs in her life right now. She starts making excuses for Martin to come round the house, having him fix, tune up, or do maintenance on practically everything she and her husband own, and doing all her business with Cuda over the phone, for delivery rather than pickup. Obviously she’s angling for an affair with the kid. Martin, for his part, is initially as skittish around Mrs. Santini as a chipmunk who smells a cat, having never had a consensual sexual experience, or one that didn’t end with razorblades and bloodshed. Thanks to Barry and his listeners, however, Martin is able to talk his way around to a frame of mind in which something resembling a normal (albeit adulterous) romantic relationship might be possible for him.

Still, a vampire must have blood, whether he’s the real thing or just a delusional psychotic with a terrible family. Cuda knows he can’t stop Martin from killing, so he compromises by forbidding him to take any victims in Braddock. If the vampire wants blood, he can fucking well hop a train into the city, or take a taxi to Monroeville. Meanwhile, Tada tries to make arrangements to have his troublesome cousin exorcised. The current priest at his church (Romero himself) is one of those wishy-washy Vatican II types, but he nevertheless puts Cuda in touch with an older colleague by the name of Father Zulemas (J. Clifford Forrest Jr.), who goes in for all the old-timey shit. Mind you, all these preparations take too long to help the amorous suburban housewife (Sara Venable) and her man on the side (Al Levitsky, who’s used about a hundred pseudonyms over the course of his career— probably because he keeps appearing in movies like Bad Penny and Water Power), or those three hobos, or those cops whom Martin leads into a deadly shootout one night when he finds himself on the verge of getting caught. But because this is a George Romero movie, it’s the murder Martin doesn’t commit that gets him into trouble.

I’ve watched Martin several times over the last 25 years or so, and I still couldn’t tell you whether I think the title character is a vampire with no powers beyond unnaturally slow aging or just a crazier-than-usual serial killer whose family elders are as bent as he is. What makes this movie so brilliant is that it draws strength from that very basic ambiguity, functioning equally well under either interpretation. Furthermore, Romero has structured his subtextual argument so that the text will support it regardless of which reading we prefer. Whatever he is, Martin’s victims are just as dead. Whether they’ve been doing it for 84 years or 18, his relatives have been keeping his secret, attempting to manage him within the family instead of doing what needs to be done. And natural or supernatural, the monster is the one who ends up commanding most of our sympathies, even though we meet him in the middle of plotting an innocent stranger’s murder. (Also, we can see the whole time that Braddock is dying by slow degrees just as surely as any village in the shadow of Castle Dracula, for reasons totally unconnected to the “vampire” who recently set up shop there.) The one thing that really changes between the supernatural interpretation and the psychological one is the exact shape of the Cuda family’s culpability. If Martin really is a vampire, then their sins are directed strictly outward, toward the victims whom they’ve allowed him to go on claiming, and the irresponsibility of their approach to the boy is mitigated somewhat by the unlikelihood of getting anyone outside the family to believe the truth about him. If, on the other hand, Martin is simply insane, then they take part in creating and sustaining his madness.

The distinct possibility that Martin’s elders and caregivers did this to him in the first place is one reason why he’s such a sympathetic monster. However, it’s equally important that Martin is such a fucked-up kid in so many relatable, commonplace ways that have nothing to do with periodic exsanguination murders. Painfully shy, socially isolated, sexually clueless, and put-upon at home, Martin is such a perfect underdog that one desperately wants to root for him. Romero gives us plenty of opportunities, too, since Martin’s peculiar structure and pacing create long stretches in which the title character is just trying to live his goddamned life like any other troubled youth. We’re encouraged to become invested in Martin’s budding romance with Mrs. Santini, to cheer on his rise to HO-scale radio stardom as the Count, to hope for an alliance to develop between him and Christina that could break both of them free from the poisoned environments of Braddock and Tada Cuda’s household. And that encouragement is so effective that it comes anew as a shock each and every time Martin heads into Pittsburgh to indulge his thirst for human blood. This, I say again, despite the fact that it’s the first thing we see Martin doing!

Those inexorably recurring reminders of the boy’s monstrousness are the means whereby Martin acquires that matchless Romero tang of unappeasable, overhanging doom. No matter how ordinary their lives may look from outside, these people are so utterly fucked that it’s impossible to imagine what a happy ending to their story would even look like. And what’s more, Romero doesn’t even need one of his famous apocalypses to secure their damnation this time. In Martin, it’s just a question of bringing together enough people whose worldviews and moral compasses are sufficiently out of whack in just the right ways.

Can you believe the B-Masters Cabal turns 20 this year? I sure don't think any of us can! Given the sheer unlikelihood of this event, we've decided to commemorate it with an entire year's worth of review roundtables— four in all. These are going to be a little different from our usual roundtables, however, because the thing we'll be celebrating is us. That is, we'll each be concentrating on the kind of coverage that's kept all of you coming back to our respective sites for all this time— and while we're at it, we'll be making a point of reviewing some films that we each would have thought we'd have gotten to a long time ago, had you asked us when we first started. For this first 20th-anniversary roundtable, we're keeping it simple, reviewing a slate of movies that we feel reflect the core competencies of our respective sites. So from me, you can expect to see something dark and horrid from the 70's, something garish and fun from the 80's, something from the 50's with a rubber-suit monster, and something smutty and European. Click the banner below to peruse the Cabal's combined offerings:

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact