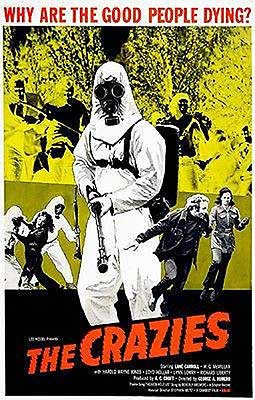

The Crazies / Codename Trixie (1973) *****

The Crazies / Codename Trixie (1973) *****

Like most artists who eventually take up residence there, George Romero never set out for the Horror Ghetto. It’s just that the genre offers unique advantages to novice filmmakers, making it abnormally easy to turn a profit on a small investment. And indeed Romero’s second feature film, There’s Always Vanilla, could scarcely have been more unlike Night of the Living Dead. There’s Always Vanilla wasn’t a big ticket-seller, though, and the scares started skulking back already in his very next project, Season of the Witch. Even that wasn’t strictly a horror movie; better to think of it as a Battle of the Sexes relationship drama that uses post-Rosemary’s Baby suburban occultism as a metaphor for both second-wave feminism and the backlash against same. But Season of the Witch didn’t make much money either, and in 1973, Romero inevitably returned to what had already worked for him once— and as it turned out, to what he was really good at anyway. The Crazies differs from its illustrious predecessor in an important respect, however. Although Night of the Living Dead certainly invites a sociopolitical reading, Romero hadn’t consciously intended it to be an allegory for anything. It was only when Duane Jones won the role of Ben that the movie began transforming into something bigger than itself. The Crazies, on the other hand, unmistakably has aims beyond merely scaring the audience. This movie, which I’ve long thought of as Romero’s secret magnum opus, is a pessimistic musing on the institutional dysfunction driving the Vietnam War, in which a similar escalating clusterfuck of doom plays out on American soil. There may be a rabies-like disease at the center of the action, but it becomes increasingly plain as the film wears on that the plague’s maddened victims are by no means the only crazies referenced in the title.

Normally, Evans City, Pennsylvania, is a quiet sort of place. A rural hamlet on the far outskirts of Pittsburgh, it’s a tight-knit community with old-fashioned values, and it enjoys a low crime rate even in the 1970’s. But tonight is not a normal night. Seemingly without provocation or even conscious awareness of what he’s doing, one of the townspeople (Regis Survinski) butchers his wife and sets fire to his own house, leaving his two children to burn to death inside. Among the first responders to the bizarre incident are volunteer firefighters David (Will MacMillan, from Christmas Evil and The Sister-in-Law) and Clank (Harold Wayne Jones, of Knightriders), together with David’s girlfriend, Judy (Lane Carroll), who works as a nurse at the small clinic run by Dr. Brookmyre (Will Disney). That means they’re also among the first to notice that both the clinic and the scene of the crime are attracting unusual attention in the form of soldiers wearing white biohazard containment suits. Major Ryder (Harvey Spillman), commanding the latter, tells Brookmyre that Evans City is under quarantine for a rare and highly contagious virus. He doesn’t mention how the town became infected, however, nor does he say precisely what the pathogen is supposed to be. He merely requisitions Brookmyre’s clinic to serve as his base of operations, and begins having his men inoculated with something or other. The doctor doesn’t like the looks of this, so he quietly sends Judy home with one hypo each of Ryder’s mystery drug for herself and David. Nobody on the scene draws any connection between the arson murder and the quarantine, but I’m sure you will.

Meanwhile, in what I take to be Washington DC, a group of important-looking men led by somebody called Brubaker (Bill Thunhurst, from Season of the Witch) tensely discuss the situation developing in Evans City. It’s much worse than Ryder is letting on— or indeed than Ryder himself is aware. Evidently a military cargo plane went down in the vicinity of the town, carrying something called TRIXIE. There are layers and layers of cover stories at work here. Ryder was told that TRIXIE was an experimental vaccine for use against Soviet bioweapons, which, in its current state of development, was nearly as dangerous as the Russian germ bombs themselves, but he was instructed to tell the people of Evans City that they were under quarantine for an unspecified disease outbreak. The truth, though, is that TRIXIE itself is a bioweapon, a synthetic malady that causes first dementia and then death for the lucky ones, incurable violent psychosis among the less fortunate. There’s no antidote, either. So you can imagine the scale of the catastrophe if the pathogen were to spread beyond the backwater community to which it seems to be confined for the moment. Ryder lacks both the manpower and the qualifications to handle the situation beyond the initial containment effort, so Brubaker and his colleagues dispatch Colonel Peckem (Lloyd Hollar), a more experienced officer with a higher security clearance, to take over from him. They also send Dr. Watts (Richard France, from Dawn of the Dead and Graveyard Shift), lead scientist on the TRIXIE project, to oversee the local medical response. Even so, Brubaker’s task force must consider the possibility that TRIXIE might breach Ryder’s quarantine. The apocalyptic implications of a TRIXIE-infected Pittsburgh are such that Brubaker gives orders for a B-52 to take up a holding pattern over Evans City with a nuclear weapon powerful enough to wipe the little town off the map. And just in case the bomb does need to be dropped, he also issues a new cover story about the crashed plane being itself a nuclear-equipped bomber. That way the government can pass off the destruction of Evans City as an unfortunate accident, should it come to that.

The biggest initial flaw in Brubaker’s plan is that there’s no medical infrastructure of any consequence inside Ryder’s quarantine line. That means Watts and his staff (to the extent that Brubaker even allows him a staff) will have virtually no chance of accomplishing their mission to develop an antidote to TRIXIE on a crash basis. Watts says as much to the soldiers who come to collect him, too, but unfortunately listening to reason is above their pay grade. The doctor ends up working with one lousy assistant (Edith Bell) in the chemistry lab at Evans City High School. It would be funny if it didn’t seem so likely to get so many people killed.

Speaking of the high school, that’s also where Ryder has been trying to relocate all the townspeople. The rationale is threefold. First and most immediately, it ought to mean an easier job in the long run for the soldiers maintaining the quarantine, since it concentrates the population well inside the perimeter. Secondly, it should enable Peckem to respond more quickly to changing circumstances, facilitating both communication between him and the civilians and close monitoring of the spread of TRIXIE symptoms. Finally and perhaps most importantly, it gives Watts ready access to the townspeople in the event that he actually manages to find a cure for the disease. Moving everyone to the high school reveals an incidental benefit, too, once Watts gets a chance to think about the problem for a while. The best chance for curing TRIXIE probably lies in finding a few people who are naturally immune to its effects, and the more different blood samples Watts is able to collect and test, the better the odds of discovering such an individual become.

This is Western Pennsylvania, though. The Appalachians. The original American reservoir of truculent Scots-Irish You-Ain’t-the-Boss-of-Me-ism. Even the mayor and the sheriff give Peckem grief, so just imagine how eager the homesteaders are to be rounded up and frog-marched to the high school! Peckem’s men don’t exactly help matters, either, by complying with the colonel’s orders to maintain strict secrecy about the nature of Evans City’s current crisis. And of course there’s TRIXIE itself to contend with. Anyone who’s ever tried to get a dementia patient to do anything contrary to their whim of the moment knows what a struggle the soldiers will be facing even in the case of the mildest symptoms. When a bad case means the patient wants to kill them, Peckem’s men might as well be back in ’Nam.

As fate would have it, David, Judy, and Clank wind up among the townspeople taken none too gently into custody at the city limits. They’re herded into a van together with a senile old man (or could he be an undiagnosed TRIXIE patient?), a flustered specimen of Evans City’s bourgeoisie by the name of Artie (Richard Liberty, from Day of the Dead and Flight of the Navigator), and Artie’s teenaged daughter, Kathy (Lynn Lowry, of I Drink Your Blood and They Came from Within). The latter three are mostly just scared and confused, but David, Judy, and Clank are pissed off at how they and their neighbors are being treated. The latter men, furthermore, demobilized from Vietnam only a few years ago— David as a fucking Green Beret! There’s very little love lost between them and the army these days, and that was before they found themselves on the sharp end of martial law. Combat-trained men without much to lose, high-handed military occupation forces, unjust violence toward civilian communities… That’s pretty much the standard recipe for a guerilla insurgency, isn’t it? And although Artie, Kathy, and Judy might seem unlikely guerillas, they know their best chance to escape from the madness gripping their little town when they see it.

At this point, anyone not familiar with George Romero’s work could be forgiven for assuming that Murphy’s Law has been fully satisfied, that everything which could go wrong in this situation either already has, or at least has already been set up to. I mean, there’s a strain of man-made super-rabies spreading slowly but surely through the populace of an isolated town, a wildly excessive yet also woefully inadequate military response making the problem worse at every step, and precious little way for anyone to tell the difference between citizens in well-justified revolt on the one hand and disease-addled axe-crazies on the other. The government’s first move was to kneecap the search for a genuine solution by placing impossible conditions on Dr. Watts. And there’s an H-bomb-laden B-52 circling overhead, awaiting orders to summarily incinerate hundreds if not thousands of American citizens. Bad, right? Sure. And if this were anybody but Romero we were talking about, then I’d even provisionally grant you bad as bad can be. But because this is Romero, you have to know that anything can always get worse. In this case, “worse” means Watts discovering that TRIXIE has found its way into the water table…

I was a teenage anarchist when I saw The Crazies for the first time. You can imagine the impression it made. Here were all my darkest suspicions of government and military dramatized in lurid and horrific form, with a cherry of kinda-sorta zombies on top! And although it’s been a long, long time since I was either a teenager or an anarchist, those suspicions of what our institutions of power are capable of have never really left me, and I would still point to The Crazies as a succinct encapsulation of why— just as I would still point to Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle (which I first read at about the same time) as a succinct encapsulation of my worries about the business world. After all, it isn’t as though paranoia, prejudice, mistrust of expertise, neurotic official secrecy, disregard for the little guy, or the reflexive preference for violent solutions have ceased to be prominent features of American politics. Indeed, what strikes me most about The Crazies today is how disturbingly timely it remains after almost 45 years.

This movie spreads my sympathies a little wider now than it did in the early 90’s, however. For instance, I used to see Colonel Peckem as plainly the villain (or at least as plainly a villain), but on this current viewing I was able to recognize how he— a black man who has climbed about as high up the ladder of command as a guy like him could plausibly hope to in this era— has been set up to fail by his superiors, and to take whatever fall may be necessary on their behalf. I also noticed this time how the racial dynamics complicate and inflame the situation on the ground in Evans City. In the eyes of the local leaders, it isn’t just martial law, but martial law imposed on them by an uppity coon; and in Peckem’s eyes, it isn’t just resistance to his authority, but resistance to his authority by a bunch of ignorant-ass rednecks. Meanwhile, I find myself softening toward Peckem’s soldiers as well. Although they look at first glance like literally faceless goons, most of them aren’t much more than kids once those gas masks come off, and they’ve been put on the shit detail of all shit details. So far as they’ve all been told, what they’re doing is for the good of both the country and Evans City specifically, and what thanks to they get? Shootouts and axe-murders, that’s what— and that’s without even factoring in the occasional soldier going TRIXIE-mad and turning a rifle or a flamethrower on his comrades.

That polyphony is the key to The Crazies’ success as a Vietnam allegory. Everybody here thinks they’re doing some version of the right thing, and all of them can articulate a justification for their actions that makes sense within their frame of reference, yet none of them ever accomplishes anything except to make a bad situation steadily worse. TRIXIE, like Stalinism, is no good for anyone, and needs to be prevented from spreading if at all possible. But TRIXIE, again like Stalinism, didn’t just come out of nowhere, and the people now directing the containment operation have their fingerprints all over the problem they now have to solve. (The parallel becomes less exact at this point, because the US government obviously didn’t invent Stalinism. However, since Ho Chi Minh turned Communist only after the Truman administration decided to back French efforts to regain control over their prewar Southeast Asian colonies, it still works well enough for the case of Vietnam in particular.) The most effective thing Brubaker and his colleagues could do would be to get the whole story out in the open, and everyone concerned on the same page regarding what’s at stake and what needs to be done. That would require them to acknowledge their part in creating the crisis, however, which would obviously put them in an uncomfortable position. At the same time, there’s a strong case to be made that acknowledgement would lead to blame-placing taking precedence over actually solving the problem, and obviously we can’t have that. So the authorities lie and bluff and bluster. That makes it look like they’re hiding something (not least because they are), and makes the people they’re trying to help mistrust and resist them. Resistance leads naturally to force, and force leads naturally to intensified resistance. Meanwhile, the original crisis rages out of control, requiring ever more drastic and oppressive measures to get a handle on it until nobody trusts anyone about anything, and nothing can get done without a fight. It isn’t simply that Romero has put the people of Evans City in a similar position to the people of Indochina, although he certainly has done that. By keeping the occupiers American, by keeping the logic of the occupation fundamentally similar, and most of all by making the resistors with whom we spend the most time a couple of ’Nam vets themselves, he creates an overlapping perspective in which it is possible to relate to both experiences of the war at once.

Earlier, I said that Romero, in making The Crazies, was going back to what worked for him. And that’s true insofar as what worked for him was a horror movie in the broadest possible sense. But upon closer examination, The Crazies is a very unusual sort of fright film, starkly different from Night of the Living Dead even despite the identical setting and the first-glance similarity between cannibal corpses and irrational, disease-maddened killers. That’s because the TRIXIE victims are not the primary locus of horror in this film. For that matter, neither are the gas-masked, containment-suited soldiers, however violent their actions and however eerie their appearance. No, the real “monster” in The Crazies is the terrible snowballing power of chaos, and of bad decisions to beget worse ones. There’s a ghastly inevitability to this story, even though it offers no shortage of turning points at which things could go differently. It’s a bit like the best of Michael Crichton’s writing in that respect, doom-laden and heavily salted with dumb, rotten luck, but never in such a way as to puncture the illusion of the characters’ agency. What these people do matters— it’s merely that the wrong thing to do always looks like the right thing from where they’re standing, and sometimes the dice just come up snake eyes. It’s a strangely impersonal sort of horror for cutthroat drive-in fare, but also a chillingly relatable one.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact