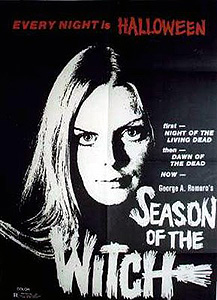

Season of the Witch/Jack’s Wife/Hungry Wives (1971) *

Season of the Witch/Jack’s Wife/Hungry Wives (1971) *

George Romero, as we all know, is just full of surprises. Unfortunately, not all of them are good. Season of the Witch/Jack’s Wife/Hungry Wives has been something of a lost film for most of the last twenty years, the victim of ownership confusion following the demise of the company for which it was made. (This controversy must have been resolved recently, because I’ve heard Season of the Witch was scheduled for re-release on videotape— by Anchor Bay, I think.) And though it pains me to say this, as a die-hard Romero fan, if any Romero flick could stand to be lost and forgotten, it would probably be Season of the Witch.

It seems promising enough at first. The credits roll over a scene of such perversity that it rapidly becomes obvious that one of the characters involved must be dreaming it. Jack Mitchell (Bill Thunhurst) is leading his wife, Joan (Jan White), through the woods, past all manner of surreal background action. Finally, he puts a leash around her neck and leads her to a dog kennel, where she is to be locked up for safe-keeping while he’s away on business for the ensuing week. The dream is Joan’s, and she wakes up then to the clamorous ringing of her alarm clock. And as the next scene shows us, her dream is strongly based in the facts and conditions of her waking life. Her husband is indeed going away on a week-long business trip, and from the way he treats her, it wouldn’t be all that surprising to see that he really did intend to stick her in a kennel ‘til he came back. When the next scene has Joan talking to her psychologist, Dr. Miller (Neil Fisher), about her dreams, and he tells her that the dreamer herself is usually the least reliable interpreter of a dream’s meaning, it starts to look as though we’re going to have some kind of Id Out of Control plot. That’s a good thing; I like those, and I bet George Romero could make a great movie out of one.

The pisser of it all is that such a prediction regarding Season of the Witch would be completely off base. Not only will we not be getting an Id Out of Control plot, we won’t be getting any kind of plot at all. None. Scarcely even a glimmer. What we get instead is Dream Sequences: The Motion Picture. Joan spends damn near the entire movie asleep, dreaming about things. She dreams about being old and ugly. (She’s about 40, and starting to worry about losing her looks.) She dreams about how Jack has plotted out her entire life for her as one big package deal. (Her subconscious knows that this package deal sucks, even if her conscious mind doesn’t.) She dreams about having affairs. (These dreams prove more than a little prophetic.) Eventually, she starts dreaming about a man in a rubber Halloween mask breaking into her house and trying to rape her. (She has this dream a lot, and one of the few brief suggestions of plot that surfaces during the movie’s 89 minutes will be related to it.) But the subject matter of her dreams is ultimately less important than the fact that she spends damn near the entire running time having them.

Most of what stands in for the AWOL plot concerns Joan’s dealings with three people. The first of these is her best friend, Shirley Randolph (Ann Muffly). Shirley is a good ten years older than Joan, and serves as an excellent case study in what Joan can expect to happen to her if she continues to lead her life as she has up to now. Shirley is miserable, lonely, bitter, at loggerheads with her neglectful husband, and entirely convinced that she has wasted her life. The second important figure in the non-plot is Gregg Williamson (Raymond Laine, who also appeared in There’s Always Vanilla, one of Romero’s few non-horror films), a professor who teaches at the college her daughter, Nikki (Joedda McClain), attends. Gregg and Nikki are friends-who-fuck (no such thing as sexual harassment law in 1971), and when Nikki runs away from home after her mother catches her in bed with him, Gregg starts having an affair with Joan in her daughter’s stead. Finally, there’s Sylvia (Esther Lapidus), the new woman in the neighborhood, and a practicing witch. After meeting Sylvia, Joan becomes increasingly fascinated by witchcraft, begins dabbling in conjuration herself, and finally joins Sylvia’s coven. This last event transpires after Joan has broken off her affair with Gregg, and blown her husband away with a shotgun when, having lost his keys, he tries to force his way into the house in a manner exactly reminiscent of the rapist in Joan’s nightmares.

I really wanted to like this movie. Failing that, I wanted at least to think of it as an interesting misfire. No such luck, though. The problem is that there’s just no movie here to like in the first place. Now it’s possible that there was supposed to be, and that George Romero and his audience have simply been screwed by producer Jack H. Harris (he of 4D Man and The Blob). The original cut of Season of the Witch was fully 130 minutes long, but after a disappointing opening week at the box office, Harris withdrew the movie from circulation and re-released it shorn of more than 40 minutes. Maybe something in those 40 minutes explained why Joan decided to become a witch. Maybe something in those 40 minutes resolved the issue of Nikki’s disappearance. (In the current version, the cops never find her, she never comes home of her own accord, and by the time the credits roll, there’s no indication that anyone even remembers the girl existed at all.) Maybe, in those 40 missing minutes, something— anything— actually happened! But then again, maybe not. It’s hard to tell what a producer’s going to cut when he decides a movie isn’t working. Most of the time, it’s non-action sequences, and it’s easy for plot points to get lost that way. But considering that Harris’s cut consists of 89 minutes of nearly non-stop dream sequences, it’s difficult to understand what would have made him keep what he kept. Could the original edit really have been so soul-crushingly dull that even this was an improvement? Is such a thing even possible? I generally don’t approve of director’s cuts, which more often than not end up being undisciplined and self-indulgent, reflecting the director’s egomania more than his “artistic vision.” But this is one case in which I might give it a try if Romero’s original 130-minute edit were to see the light of day— although I can tell you right now that I’m not exactly twitching with anticipation for the opportunity.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact