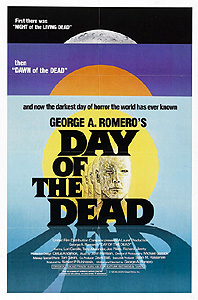

Day of the Dead (1985) ***

Day of the Dead (1985) ***

George Romero likes to say that each of his zombie movies is in some sense about the decade in which it was filmed. Of the three, it’s easiest to see how that’s the case with Day of the Dead. It wasn’t for nothing that the 1980’s were a sort of golden age for post-apocalypse movies, and it seems only natural that the Romero zombie film that takes place after the living dead have achieved effectively undisputed ownership of the world should have been made during that decade. Unfortunately, the 1980’s were also the decade during which Romero had his brief brush with mainstream success, and it would appear that the experience blunted the director’s edge a bit. Though Day of the Dead is easily Romero’s most personal 80’s horror project (and also the scene of the opening skirmish in his ongoing battle with the powers that be in Hollywood), it lacks the power and the focus of his work from the 70’s. It breaks little new ground in the genre, and its social commentary— traditionally one of the great strengths of Romero’s horror movies— is surprisingly inarticulate. Instead of latching onto a small number of interrelated themes and attacking them in a merciless and systematic manner, Day of the Dead seems to sputter in overwhelmed exasperation at just about everything. But Romero is still Romero, even when he isn’t at the top of his game, and Day of the Dead does at least succeed in making a suitable closing argument for what might plausibly be seen as the main overarching theme of the entire trilogy: no matter how dire the threat from outside, man will always be his own worst enemy.

For once, the scene of the action is not western Pennsylvania, but central Florida. In one of the virtually indestructible underground bunkers which were built to house the essential functions of the government and military in the event of a full-scale nuclear war, a small team of scientists searches for a solution to the zombie problem, under the protection of what was once at least a battalion of the US Army. It isn’t going well. The project was slapped together on short notice, in an extremely haphazard manner, and neither the researchers nor the soldiers nor Billy McDermott (Jarlath Conroy), the civilian radio operator charged with keeping in touch with the rapidly shrinking outside world, have the resources at hand to perform their roles in the scheme properly. Dr. Logan (Richard Liberty, of The Crazies and The Final Countdown), the head of the researchers, has little of the sophisticated gear he needs to determine the hows and whys of the zombie plague, while his two assistants, Sarah (Lori Cardille) and Fisher (John Amplas, from Midnight and Creepshow), have seen their own work grind practically to a dead halt. A single battalion might have seemed at first like sufficient protection for three scientists, a radioman, and a helicopter pilot, but now that the walking dead outnumber the living by some 400,000 to one (according to Logan’s estimates), such a force would be woefully inadequate even if attrition hadn’t winnowed it down to less than platoon strength. McDermott’s vacuum-tube radio rig has nothing like the power necessary to reach beyond the now-depopulated Deep South in the absence of the network of relay stations which once dotted the countryside, and the team’s only hope for making contact with whatever may be left of the rest of the world is for John the pilot (The Horror Show’s Terry Alexander) to take Sarah and Billy out on periodic scouting missions to the surrounding cities. As we join the party, the radius of these reconnaissance flights has reached 150 miles, and there is still no sign of a single living human apart from the dwindling numbers at the base itself.

Speaking of dwindling numbers, the most recent death among the soldiers is one that promises major changes— and not for the better— in the way things are done in and around the bunker. The troops have now lost their commanding officer to one of the corralled zombies which Logan keeps for experimental use, and the accompanying natural increase in their resentment of the civilian scientists would be bad enough all by itself. But what’s worse, the next officer down in the chain of command, Captain Rhodes (Joseph Pilato, whom you’ll need sharp eyes to spot in Alienator and Wishmaster), is an outright psychopath. The way Rhodes sees it, the major’s death leaves him king of the world. To be fair, this is not an unreasonable position to take in light of what Rhodes can see of the situation upstairs, but since the model for his governance appears to be Ivan the Terrible or Vlad the Impaler, his accession to command promises to be bad news for just about everybody. Even Privates Rickles (Ralph Marreno, of Tales from the Darkside: The Movie) and Steel (Gary Howard Klar), the captain’s most loyal men, have good reason to fear their new commander’s violent and unpredictable disposition. The danger is much worse for the scientists, and for Miguel Salazar (Antone DiLeo, from Knightriders and Two Evil Eyes), the soldier who has become romantically attached to Sarah, and who is now coming visibly unglued under the strain of the seemingly futile daily struggle against the undead.

As it happens, the one man in the bunker who has no apparent fear of Captain Rhodes is Dr. Logan. Whatever else may happen, Logan understands that his work is absolutely the last hope for human civilization as we have known it, and he never misses an opportunity to rub Rhodes’s face in that humbling fact. Whenever Rhodes threatens to pack up his soldiers and leave the civilians behind in the bunker to fend for themselves against the zombies, Logan simply confronts him with the one vital question to which he and his men will never find an answer by themselves: “Where will you go?” Asking “Where will you go?” has thus far kept Logan sufficiently unsupervised to do a great many things which Rhodes would never stand for if he knew about them— like employing the major’s reanimated body in a series of experiments which has allowed him to pinpoint the exact region of the brain which must remain operative for the zombies to function— and has given him time to make considerable headway on a project which the captain and his men would find horrifying even to consider. Reasoning that present population ratios, combined with the decade-plus lifespan which his findings project for the average zombie, preclude the living from ever being rid of the dead, Logan has invested most of his efforts in an attempt to domesticate a zombie, training it to be harmless to live human beings. Bub (The Stand’s Howard Sherman), as Logan calls his undead pupil, can not only be trusted (well, mostly) not to attack people, he is able to understand and comply with simple commands and can access a surprising number of the memories from his first lifetime. The key to this progress, or so Logan maintains, is the same simple reward/ punishment regime that we use to condition any trainable animal. Of course, Rhodes isn’t going to like it very much when he finds out exactly what sort of “rewards” Logan has been giving Bub all this time, and when Rhodes doesn’t like something, all kinds of crazy, bad things are just about certain to happen.

To some extent, the trouble with Day of the Dead is that, structurally, it is mostly a simple rehash of Night of the Living Dead. A bunch of people are holed up in a building, getting on each other’s nerves, while the zombies wait patiently outside for the humans’ mutual antagonisms to give them an opening to attack. Having already seen Romero play this card as well as it was ever going to be played by anybody, it’s hard not to look at Day of the Dead and ask what the point of doing it all again is supposed to be. But more importantly, this movie comes up short in comparison to its predecessor because the human drama inside the bunker is so exaggeratedly self-destructive that you kind of wish the zombies would find their way in sooner rather than later so that we can just get on with it. Captain Rhodes is so thoroughly and obviously evil, and everything he does and says is so obviously wrong, that it becomes impossible to understand why even his lackeys— whom, let us not forget, he goes out of his way to threaten and intimidate for no discernable reason— wouldn’t get sick of him and rig a grenade to the flush handle on his office toilet. During the Vietnam War (which looks to be the main source of Romero’s vision of the US military), scads of officers were killed on the sly by their own men for far less offensive conduct than what Rhodes does here! And in writing Steel and Rickles, Romeo stoops to exactly the form of easy demonization which he so scrupulously eschewed in Night of the Living Dead— he makes them racists, even as he draws attention to a much more potent reason for them to hate and resent Salazar than mere ethnic bigotry. Miguel, after all, is the only man in the bunker who is getting laid, and early on, Romero gives several of the other soldiers (and Rhodes especially) some lines which hint at what is likely to become of Sarah should the zombies ever get Salazar. Yet nothing comes of this powerfully ugly piece of setup, even after Miguel is bitten in an attempt to round up another pair of experimental subjects for Dr. Logan, and the strife between Salazar and his comrades is left to rest on the more pedestrian foundation of race— and for most of the film, rest is just about all it does, too.

It’s also disappointing to see how scattershot Day of the Dead is thematically. Romero’s longstanding pessimism regarding human nature had reached its absolute zenith by this point in his career, and while that’s entirely understandable given the way things had been going during the first half of the 80’s, “the human race is fucked” is just slightly too grand a premise to do right by in a film that takes place almost completely underground, with a cast of characters whose lives could scarcely be any less like that of the average person. In order to squeeze in all of the things he wants to say under those conditions, Romero would appear to have had little choice but to resort to the constant parade of straw men and easy targets that he gives us here. Two things make this terribly unfortunate (beyond the fact that it’s just plain beneath him). The first is that there isn’t enough time available to go into much detail on any one rhetorical point, with the result that considerable swaths of intellectual territory are left unexplored. For example, what are we to make of Romero’s obvious sympathy with John’s anti-rational Luddism (“Maybe the Creator decided we were getting too big for our britches trying to figure his shit out”) in the context of a filmography which seems to contend, when taken as a whole, that man’s fatal flaw is precisely the stubborn persistence of his ancient irrationalities? The second big problem with Romero’s frequent resort to cheap shots in this outing is that it ends up undermining to some extent the main polemical thrust of the movie. The argument that people will always be able to do more damage to themselves and to each other than even the most nightmarishly apocalyptic external force has always been one of the sharpest tools in Romero’s kit, and it receives its starkest, most extreme iteration in Day of the Dead, but it’s hard to give the idea its full weight when the characters dramatizing it simply are not recognizable as believable, real-world people. Rhodes, Steel, Rickles, Logan, Salazar— even Sarah and John to some extent— are cartoons, each and every one of them, and their unreality cushions what should have been the knockout blow of the zombie trilogy.

But there are still a few things which Day of the Dead gets absolutely right in spite of its flaws. Most importantly, this is, as Romero intended, the grimmest, bleakest, and most spiritually oppressive of the living dead films, even despite being the one which makes the closest approach to a happy ending. The movie attains depths of utter hopelessness that neither of its predecessors can match, together with a strong sense that said hopelessness is fully deserved by its protagonists and indeed their entire species. The bunker would be a hellish enough place to live even without the thousands upon thousands of zombies waiting outside its gates, or the knowledge that life within it is carried on wholly at the sufferance of a capricious, bloodthirsty lunatic. And speaking of the undead, because this was the first time in his independent career when money was, if not no object exactly, then at least a much smaller object than it had been in the past, Day of the Dead is able to feature by far the most gruesome and believably dead zombies Romero had yet employed. Whereas makeup chief Tom Savini had been forced, on Dawn of the Dead, to limit the full exercise of his talents to just a handful of featured zombies, nearly all of the ghouls in this installment sport elaborate gore and decay prostheses and a personal touch to their makeup design which had been far beyond the means of any previous Romero production except possibly Creepshow. The masses of living dead are more convincing here than they had ever been before, and because Romero never plays them for laughs this time around (not even the one zombie in the climactic assault on the bunker who shambles around in a complete clown costume!), they give off more sheer menace than they have at any point since that first, shocking scene of explicit flesh-eating in Night of the Living Dead. On the strength of that alone, it seems plausible to me that, had it been anyone but Romero sitting in the big chair, Day of the Dead would be remembered much more favorably today— the fans’ disappointment has less to do, I think, with the movie’s inherent quality or lack thereof than it does with how much more Romero’s previous work had led us to expect of him. Coming after the preceding two entries in the series, plain old good just isn’t good enough.

Because you can never have too many putrescent corpses shambling about chewing on people, the B-Masters Cabal has decided to join Cold Fusion Video in dedicating the month of October to zombies, zombies, and more zombies. Click the banner below to drop in on Undead Central.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact