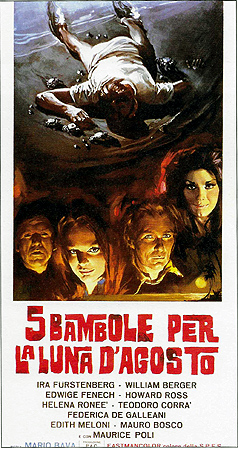

5 Dolls for an August Moon / Island of Terror / 5 Bambole per la Luna d’Agosto (1970) *½

5 Dolls for an August Moon / Island of Terror / 5 Bambole per la Luna d’Agosto (1970) *½

Mario Bava always claimed to think very little of his own films. He didn’t usually put it as memorably as he did in a 1979 interview for L’Espresso magazine, when he told Dante Matelli, “In my entire career, I made only big bullshits,” but the sentiment behind that quote is more or less typical of him. It seems hard to square that attitude with the obvious care and craftsmanship that Bava brought even to his frequent uncredited work as a second-unit director or special effects technician, but it isn’t totally inexplicable. His father, Eugenio Bava (the first special effects master of the Italian movie industry, whom I hope to find an excuse to deal with directly one of these days), had an almost pathological regard for modesty, so one can equally well imagine Mario cultivating a habit of affected self-deprecation or developing a genuine blind spot for his own abilities and accomplishments. Either way, it should be obvious by now that I, for one, strenuously disagree with what Bava was always saying about himself. Or at any rate, I disagree in general. Everybody has the occasional off day, though, and there are a handful of Mario Bava movies for which “big bullshit” is a perfectly fair assessment. 5 Dolls for an August Moon, his penultimate giallo, is one of them.

It does at least get off to an interesting start. At his ultra-modern villa on a private island somewhere, wealthy businessman George Sagan (Teodoro Corra, from The Profanation and The Other Canterbury Tales) is throwing a party. (By the way, depending on which version of the movie you’re watching, George’s last name might be Stark instead. Evidently the English-language dub uses somewhat different names for most of the characters from the subtitled Italian-language print that I saw.) In addition to George and his wife, Jill (Edith Meloni), there are three men and three women in attendance (plus a girl spying on the proceedings from outside), and right now, all eyes are on a big-haired brunette (Edwige Fenech, of Hostel, Part II and All the Colors of the Dark) as she performs a lurid table dance on the wet bar. Every external source I’ve consulted calls her “Marie,” but the Italian print bewilderingly identifies her only as “Pook.” After she climbs down from her perch and gyrates over to George, he launches into a bizarre speech about a ritual of sacrifice to appease the gods, and ties her to a convenient piece of furniture. Then Jacques the houseboy— or Charles the houseboy (he’s Mauro Bosco in any event)— comes around with a platter full of knives to distribute among the guests. George plays the point of his menacingly over Marie’s body (I’m sorry— I just can’t bring myself to think of her as “Pook,” nevermind that I’m using the subtitles’ names for everyone else), nattering all the while about the gods’ demands. Then the lights go out, and Marie screams. When they come back on again a moment later, one of the knives is protruding from the woman’s chest. Marie’s husband, Nick (Maurice Poli, from Rabid Dogs and Papaya, Love Goddess of the Cannibals), admits that it’s his, but says that somebody else took it away from him in the dark. The only thing that could have made this setup more of a cliché is if the partygoers had been conducting a séance instead of a pagan rite, but don’t get too comfortable yet. It’s all been a trick, you see. The knife is merely tangled in the left cup of Marie’s halter top, and the viscous, red liquid smeared all over her breast is just berry preserves or some such thing. All the guests have a good laugh at the prank, and resume reveling.

That’s not to say, though, that there isn’t serious business in back of the party. The guest of honor is a chemist named Fritz Larsen— or Gary Farrell (William Berger, from Devilfish and The Sinister Eyes of Dr. Orloff)— who has recently developed a new industrial resin that could be worth a fortune to whomever can put it into production first. George, Nick, and the fourth man, Jack Davidson (Howard Ross, of Hercules Against the Mongols and Legend of the Wolf Woman), have formed a consortium in the hope of becoming those whoevers, and each has come to the villa bearing a check for a million dollars (or presumably its equivalent in lire). Fritz doesn’t want to sell, however. No, it isn’t that the bid is too stingy, so Nick’s and George’s respective efforts to go behind their partners’ backs with even bigger sums will avail them nothing. It’s simply that the improvement in industry standards (whichever industry we’re talking about here) promised by the new resin would be of such universal benefit that Fritz prefers to offer it on an open-license basis once he’s had a chance to hone the formula a little more. That kind of thinking is so alien to the would-be buyers’ minds, though, that they are unable to accept it as Fritz’s real position. George and Nick especially set themselves to feeling out other desires that the scientist might have, beginning when George instructs Jill to seduce him. Nor are they the only ones to react with exasperation to Fritz’s recalcitrance. The chemist has a wife of his own, and Trudy (Ira von Fürstenberg, from Homo Eroticus and Nights and Loves of Don Juan) sure would like to have $3 million to play with.

Even so, it looks at first like the issue that finally sets these people at each other’s throats is not money, but sex. After all the men have gone to bed, three of their wives sneak out of the house for secret assignations. Trudy and Jill rendezvous in the garden to take up anew the lesbian affair that they apparently had going during their bachelorette days, while Marie boards George’s yacht to fuck Jacques. Her tryst doesn’t go nearly as well as the other women’s, however, because someone has beaten her to the boat, and stabbed the poor houseboy to death. Did Nick know what she was up to? Did Jill, who also has a history of fucking Jacques, become territorial despite having both a husband and a girlfriend as well? Or could the murder instead have something to do with Isabel (Ely Galleani, from Baba Yaga and Emanuelle in Bangkok), the young girl we saw spying on the party before, who continues to snoop suspiciously all around the island?

The gang at the villa are in for a doubly rude awakening the next morning, for not only is Jacques dead, but the yacht is nowhere to be found, meaning that there’s no longer any way off the island. Jack and his wife, Peg (Baron Blood’s Helena Ronee), are pretty laid back about being trapped in the middle of nowhere with a murderer, but the rest of the guests take it badly. Not badly enough, mind you, to take George and Nick’s minds off of Fritz’s resin formula, but badly just the same. Then the next night, Fritz disappears, dragged away into the surf after apparently being shot. Now it looks like Isabel pulled the trigger there, but since this is a giallo, we should at least leave open in our minds the possibility that Bava is fucking with us, especially given the very ambiguous editing of the scene when the chemist seemingly meets his end. You might think that with Fritz gone, the other men would abandon their efforts to gain his formula (hard to buy a patent from a dead man, after all), but from the way the murder rate around the villa accelerates in the aftermath, it looks like the competitive tensions among the partners are instead releasing themselves in the most vicious and primitive manner.

I may not know how far to believe “I made only big bullshits,” but I’m sure Bava was completely on the level when he repeatedly identified 5 Dolls for an August Moon as his worst movie. His gripes about it are too insightful, to accurate, too earnestly rueful to be dismissed as false modesty. Again I don’t agree, exactly (5 Dolls for an August Moon doesn’t even approach the dreadfulness of Dr. Goldfoot and the Girl Bombs), but everything about this movie smacks of Bava making the best of what he knew from the start was a bad situation. The problems begin with the script, which Bava correctly disdained as a crudely unimaginative copy of Ten Little Indians without a tenth of the prototype’s logical consistency. He was no stranger to shooting from sub-par screenplays, of course. Indeed, by this point in his career, he had something of a standard approach to the problem, in which he’d trade on his producers’ nigh-universal disrespect for writers to get a few days’ delay added to the shooting schedule for rewrites. In this case, however, the producer liked the screenplay just fine, and wanted the movie hustled into production. Bava could do no more than to add a coda in which two seemingly innocent characters turn out to have criminal pasts, injecting a bit of honest surprise into an otherwise rote whocareswhodunnit plot. (Note that 5 Dolls for an August Moon thus comes across as a sort of botched testbed for Twitch of the Death Nerve, in which nobody is innocent either.) It isn’t enough, though, to solve 5 Dolls for an August Moon’s fundamental problem, which is that it’s the kind of murder mystery that stumps the audience not through misdirection, but because the crimes and the motives behind them don’t make any fucking sense. I’m not sure which is more incredible, that a murder mystery never bothers to establish which victims belong to which perpetrator, or that the story is so shoddily constructed that it actually doesn’t matter.

It also doesn’t help that the characters are so thinly written that they barely even have attributes, let alone personalities. For the first hour of the film, you’ll be too busy trying to keep straight who the hell any of these people are to give much thought to who’s killing whom or why. Indeed, some of the pieces never do fall into place, like what Isabel is even doing on George’s island, or what we’re really supposed to make of the relationship between her and Fritz that’s revealed at the climax. The casting contributes to character confusion, too, because Edwige Fenech, Edith Meloni, and Ira von Fürstenberg all look remarkably similar. Three pallid brunettes with inexpressive faces are two too many when you have no idea what anyone’s names, relationships, or agendas are supposed to be.

Whatever worth 5 Dolls for an August Moon possesses is due almost entirely to Mario Bava’s skill as a creator and manipulator of images. For example, the sequence in which two struggling characters knock over a vessel full of variously sized glass balls, and the camera leaves the antagonists to their business in order to follow the torrent of rolling orbs all the way to the site of a third character’s suicide, deserves to be in a much better film. The same goes for Bava’s playing up of the contrast between the remote wildness of the island exteriors and the stylish artificiality of the environment George has made for himself in the villa. The visual highlight of 5 Dolls for an August Moon, however, is the device Bava uses to stand in for the “and then there were x” verses in Ten Little Indians. In the screenplay as written, the running body count was kept by scenes in which the survivors buried the latest victim in the sand of a high dune, each beneath a rude wooden cross. In place of this DIY cemetery, spreading like a patch of weeds with each new murder, Bava substituted the villa’s walk-in freezer. Hung at the start with sides of meat, the freezer becomes even more grisly as the spare hooks are taken up by corpses, hastily wrapped in plastic to prevent them from contaminating the raw materials for dinners yet to come. In stark contrast to everything else in the movie, that means of stowing the bodies is eminently logical, yet it creates at the same time an excuse for one of the beautifully horrible compositions that crop up so often in Bava’s work, and which make him a director worthy of attention even when the movie as a whole is a dud.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact