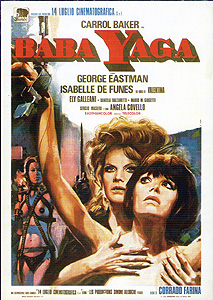

Baba Yaga/Devil Witch/Baba Yaga, Devil Witch/Kiss Me, Kill Me/Black Magic (1973)**

Baba Yaga/Devil Witch/Baba Yaga, Devil Witch/Kiss Me, Kill Me/Black Magic (1973)**

It’s been a big couple of years for comic book movies. Inevitably, Spider Man, Hulk, and the X-Men films have drawn the most attention, but what I find especially interesting is that comic book movies in this country are finally starting to branch out beyond the superhero genre. Ghost World, for example, had its origin in comics, as did American Splendor. But while this is a new development in Hollywood, the rest of the movie-producing world figured out a long time ago that there was much more to comics than beefcake in tights; Japan has been turning out manga-based movies in all genres practically since the beginning, and although they’ve attracted less notice in the States than the Japanese, the Europeans got an early start, too. Baba Yaga/Devil Witch/Kiss Me, Kill Me is one such comic book flick from Europe, which was made during what might plausibly be called the golden age of such things, the period spanning the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. Its ink-and-paper antecedent was a storyline from the long-running Valentina strip, possibly the best known original creation of the recently deceased Milanese cartoonist Guido Crepax. (His best known creations period would probably be his graphic adaptations of The Story of O and the Marquis de Sade’s Justine.) Director Corrado Farina is obviously a devoted fan of Crepax’s work, and tried very hard to capture its feel on film. Unfortunately, with Baba Yaga, he missed the mark far more often than he succeeded.

There’s a party going on somewhere in Milan. Among the guests at this party are comic book artist Guido Crepax (who won’t figure in the story at all, but whose inclusion marks the first of several admirable attempts by the filmmakers to match the artist’s reality-bending style), struggling left-wing film director Arno Treves (George Eastman, from The Grim Reaper and Monster Hunter), and a similarly anti-establishment photographer named Valentina Rosselli (Isabelle de Funès). All three end up leaving together when the party breaks up (Crepax and Treves are old friends, and Arno desperately wants to fuck Valentina), but Valentina insists upon being dropped off and walking the rest of the way home after riding only a few blocks with the two men. I’m guessing it has something to do with having to sit on the lap of a guy who’s made no secret about wanting to stick his cock in her— Guido’s car is a two-seater. While walking back to her place, Valentina and the cute little puppy she had stopped to pet are nearly run over by a glamorous-looking, 40-ish blonde woman (Carroll Baker, from The Sweet Body of Deborah and the other movie called Kiss Me, Kill Me) driving an antique Rolls Royce. Feeling guilty about nearly killing a total stranger, the woman offers— no, demands— to drive Valentina home. On the way, she behaves very strangely, talking about how their chance meeting was cosmically foreordained and snatching the garter clip from one of Valentina’s stockings. Her only explanation is that she requires “a personal object” of Valentina’s, for some purpose she refuses to explain. She promises to bring it back to her tomorrow, however, and lets Valentina out of the car with an admonition not to forget her name— Baba Yaga.

That by itself should tell Valentina that trouble is ahead. Baba Yaga, you see, is a character from Russian folklore, a sort of witch-ogress creature who eats children and possesses an array of dangerous supernatural powers. Now it’s immediately obvious that this Baba Yaga is a very different sort from her legendary namesake, but I still wouldn’t trust a woman with that name any more than I’d trust a guy named “Alucard.” Evidently Valentina isn’t up on her Slavic folklore, though, because when Baba Yaga begins worming her way into the younger woman’s life, she figures she’s just gotten herself mixed up with an aging lesbian. But when Baba Yaga comes over to return the garter clip as promised, she also casts some sort of spell over Valentina’s favorite camera that causes all kinds of bad things to happen to anyone or anything it photographs. This first comes out when Valentina snaps a photo of Arno at work, and the movie camera the director is using jams the moment she presses the shutter button on hers. Then one of her models falls into a swoon during a fashion shoot on which Valentina employs the cursed camera. What finally convinces Valentina to start using her backup equipment for a while is the outcome of her efforts to document some kind of street protest on the front steps of a cathedral downtown. One of the protesters drops dead when Valentina takes his picture.

Meanwhile, Valentina has been spending more time around Baba Yaga than is probably healthy. She takes her new admirer up on an offer to come and take pictures in the huge old house she lives in, and encounters some strange, strange shit while she’s at it. For one thing, the junk in Baba Yaga’s attic is not at all what you expect to find in such a place. I mean, how many middle-aged rich ladies do you know who collect whips, shackles, steel gauntlets, and knee-high patent leather boots? Or who dress their porcelain dolls in miniature studded-leather bondage harnesses? But the most alarming thing Valentina finds at Baba Yaga’s house is the bottomless pit in the back corner of her parlor. The hole is hidden under the rug, and Valentina almost falls into it before she figures out what’s happening. When she tests the hole’s depth by dropping an empty film canister into it, she never does hear the thing hit bottom. Valentina apparently isn’t all that swift, though, because after all that, she still doesn’t see what a bad idea it is to accept when Baba Yaga gives her Annette the Bondage Doll as a present, claiming that it will keep her safe from all harm if she keeps it with her constantly.

It doesn’t take Valentina too long to catch on, though. Her first hint comes when she develops the photos she took over at Baba Yaga’s place. None of the eerie shit in the attic— the shackles, the whips, the fetish boots— shows up in the developed pictures, and Annette appears clad in a perfectly ordinary dress. Then Valentina notices that the doll often turns up in places where she doesn’t remember putting it. Finally, Valentina is faced with incontrovertible evidence that Annette is alive. Two of her frequent collaborators come by her apartment to shoot photos for a series of underwear ads, and the power briefly goes out after they’re finished. While the lights are out, something sticks the female model in the thigh, and after power is restored, Valentia notices two things that are out of place in the room. Annette is now lying on the floor beside the model, holding a long hairpin, and the cursed camera is now registering that an entire roll of film has been shot, even though Valentina specifically set it aside in favor of one that doesn’t exhibit malign supernatural powers. Valentina gets so creeped out that she rushes off to talk to Arno about all the strange experiences she’s had since the night she met Baba Yaga, and the director suggests that she develop the roll of film that her camera apparently shot by itself, even though the complete darkness in the room at the time should mean that all the pictures will come out blank. They don’t. Instead, they show Annette changing into a living woman (Ely Galleani, from A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin and Emanuelle in Bangkok) and pricking the model with her hairpin. Shortly thereafter, Valentina receives a phone call from a friend of hers on the fashion photography circuit, informing her that the model in question has suddenly, inexplicably died. Baba Yaga calls, too, and insists that Valentina come over to her house alone that very night. Doing so is just as bad an idea as it sounds...

Corrado Farina has said that Roger Vadim’s Barbarella was a big influence on Baba Yaga, in the sense that Farina looked to that earlier movie as an example of what not to do while adapting Valentina to the screen. In that light, I find it really fascinating that Farina made nearly all of the same mistakes, creating a movie that is unsatisfying in almost exactly the same way. Both Vadim and Farina used their lead actresses in ways that thoroughly sabotaged the characters they played, and both were only half-successful in translating the tone of their source material to film. Isabelle de Funès is a major drag on Baba Yaga. The only thing her performance has in common with Crepax’s Valentina is that both women have the same frail, skeletal build. Funès never comes close to capturing the character’s languorous sensuality, or to conveying the sense I always get while reading Valentina that she goes through her waking life the way most of us go through our dreams— as if her impetus for doing things came not from her own will, but from some impersonal outside force. This is a major failing, because one of the most distinctive features of the Valentina stories I’ve read is that dreams and fantasies play a significant role in advancing their rather loose plots (in fact, some of the shorter strips are nothing but dreams and fantasies), and that it is often difficult to tell the difference between a dreaming Valentina and a wakeful one. Farina tries to bring that across (nearly every transition between one day and the next is marked by extremely strange dream sequences that capture Crepax’s style perfectly), but Funès is just too businesslike in her performance for it to work properly.

But of even greater importance, Farina ditches what would almost certainly be the first thing a newcomer to Crepax’s work would notice about it— its totally unabashed smuttiness. It isn’t for nothing that Crepax was often hailed as the world’s sexiest cartoonist, but Baba Yaga is usually so coy in its dealings with sex that it’s hard to believe it was made in 1973. This was Barbarella’s most obvious failing, too, but at least Vadim put some well-crafted tease into the movie to partially make up for it. Baba Yaga, on the other hand, is a remarkably un-sexy film, even when its title character is going all-out to seduce Valentina, or when Arno finally does succeed in getting the object of his affections into bed. Part of that stems from Funès’s woodenness, and part of it might also stem from George Eastman’s miscasting in a theoretically romantic part, but I think most of it has to do with Farina’s treatment of the material in a manner completely at odds with the comics. He seems to find all the sex in the story at least faintly embarrassing, which is something you’ll never, ever get from Guido Crepax.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact