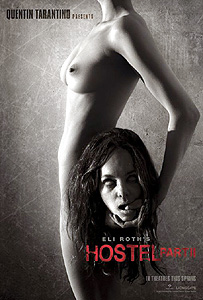

Hostel, Part II (2007) ***

Hostel, Part II (2007) ***

Sequels so often are little more than exercises in diminishing returns that I don’t generally get my hopes for them up very high, although my completist tendencies do frequently lead me to watch the things anyway, regardless of my expectations. Naturally that goes double for sequels to movies that I consider failures— filmmaking is an endeavor in which “there’s nowhere to go but up from here” is simply never true. Hostel, Part II therefore comes as a welcome surprise. It is the rarest form of sequel, one that not only improves markedly upon its predecessor, but can justly be described as the movie its creators ought to have made in the first place. Just as bracingly grisly as the original, Part II is at the same time more tonally coherent, more thoughtfully structured, more clever in its genre in-jokes, and more effective even in its attempts at satire. Best of all, it corrects the two most crippling flaws of the first film, building its story around characters whom we don’t want to seen torn into little, bitty pieces, and displaying a wholly unexpected recognition on writer/director Eli Roth’s part that women might possibly be people.

And as if all that weren’t staggering enough, Hostel, Part II begins by retroactively humanizing that cocksucker Paxton (a returning Jay Hernandez)! The last two fingers on his left hand weren’t all that Paxton lost forever as a result of his confinement in and escape from the Slovakian murder brothel that was very nearly the final stop on his European backpacking tour. Even back home in America, he lives in constant fear of being tracked down by agents of the Russian mob that operates the ghoulish attraction, and he has enjoyed not a second’s peace of mind since making his getaway. Beyond that, he’s haunted by the memory of the things he had to do in order to survive— to say nothing of the things he did that weren’t strictly necessary, but that seemed to be called for under the circumstances at the time. Paxton’s girlfriend, Stephanie (Jordan Ladd, from Grindhouse and Cabin Fever), has tried to be understanding, even to the extent of going into hiding with him at her grandmother’s house in the country, but she’s finally coming to realize that the kind of help Paxton needs is beyond her ability to provide. She’s right, as it happens, but not in the way she imagines. The operators of the murder brothel really do have eyes and ears everywhere, and only a day or two after the retreat to Grandma’s house, Stephanie awakens to find her boyfriend sitting, decapitated, at the breakfast table. Some hours later, on the other side of the world, a motorcycle courier presents a well-dressed, 60-ish man (Milan Kňažko) with a box just the right size to contain Paxton’s missing head.

Meanwhile, in Rome, American college students Beth (Lauren German, of Dead Above Ground and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre) and Whitney (Bijou Phillips, from The Wizard of Gore and It’s Alive) are preparing to embark via overnight train for a weekend in Prague. Although they envision the trip as an undertaking for just the two of them, the pair becomes a foursome by the time they’re actually on the train. Beth and Whitney are both enrolled in a figure-drawing class (their teacher is Edwige Fenech, famous for films like 5 Dolls for an August Moon and Strip Nude for Your Killer, coming out of retirement as a fan-favor to Roth), and their classmate, Lorna (Heather Matarazzo, of Scream 3 and The Devil’s Advocate), talks Beth into bringing her along. And when the girls settle in aboard the train’s lounge car, they discover that one of the models from their class— a vaguely Slavic woman named Axelle (Vera Jordanova), who seems to have developed something of a crush on Beth— has decided to follow them eastward. Whitney may resent both party-crashers, but Axelle quickly makes herself useful by retrieving Lorna’s iPod from a thief, and then helping the American girls evade a gang of creepy Italian football hooligans from whom Whitney had foolishly tried to buy some ecstasy. Axelle also comes up with an idea that redefines the whole trip, mentioning a spa outside of Bratislava where she periodically goes to decompress. The encounter with the hooligans has left both Beth and Lorna feeling like they’ve “had enough of gross guys for one weekend,” and Whitney, outvoted, agrees to blow off Prague for Axelle’s Slovakian spa. Axelle even offers to take them to a place she knows in town where they can all stay dirt cheap.

Why yes— that would be a certain familiar youth hostel, which suggests to me that posing for art students actually represents only a trivial fraction of Axelle’s income. While she shows the Americans around town, the desk clerk scans their passport photos and uploads them to a secure website to serve as lots in an online auction. One of the winners (Monika Malakova) we’ll see only in the process of claiming her prize, lacerating the virginal Lorna with a scythe so as to bathe in her blood, Erzsebet Bathory-style. The man who puts in the winning bid on Beth and Whitney, however, swiftly becomes a major figure indeed. This is Todd (Richard Burgi, from Friday the 13th and Starship Troopers 2: Hero of the Federation), a coked-up, macho alpha-bastard who has a really weird concept of charity. Although Todd bought Whitney for himself as one would expect, Beth is to be a birthday present for his friend, Stuart (Roger Bart, of The Midnight Meat Train and The Stepford Wives). The men’s relationship is rather like a depraved version of the one between John Blane and Peter Martin in Westworld. Todd sees himself as doing an enormous favor for Stuart, above and beyond the material generosity embodied in the tens of thousands of dollars he paid on his friend’s behalf for Beth’s life. Stuart is a weakling in Todd’s assessment, fatally domesticated by an emasculating wife and two kids who are forever needing things from him, and Todd figures an Eastern European murder vacation will be just the thing to make a man of Stuart once more. Obviously, then, Todd’s affection for the other man is leavened with a massive contempt, and the main pattern visible in their interaction consists of Stuart defensively acquiescing to whatever Todd sees fit to bully him into for his own supposed good. And just as in Westworld, the main provocation for that bullying is Stuart’s visible lack of commitment to the premise underlying the trip— only here that strain of cognitive dissonance is a far more serious matter. For one thing, it won’t be a robot that Stuart tortures to death, and for another, the murder brothel understandably does not permit its customers to change their minds once they’ve set foot on the grounds.

Hostel, Part II has us spend a lot more time with Todd and Stuart than the original Hostel devoted to any of its murder tourists, and more importantly, it goes so far as to treat them as viewpoint characters. In doing so, the sequel opens up a huge new vista of insight into the workings of both its fictional world and the minds of the villains inhabiting it, making this easily the smartest movie of its much-reviled type that I’ve seen thus far. Delving into the bad guys’ psychology improves the credibility of what had originally been a fairly ludicrous scenario, and helps to circumvent one of Hostel’s most serious failings. The last time around, Eli Roth tried to have it both ways, lampooning American paranoia about a hostile and peril-ridden outside world even as he pandered to it, and the pandering won out in the end. Here, though, he treats the featured villains as fairly well-rounded characters whose motivations we might recognize, even if the behavior in which those motivations find expression is monstrous and insane. Todd and Stuart are not merely some inscrutable, foreign Other— and neither, for that matter, is Sasha the head-collecting mob boss, who becomes an increasingly significant figure as the film wears on. Lawless, bloodthirsty corruption in Hostel, Part II isn’t something that goes on out there, but rather something that penetrates all societies, a global system that anyone, anywhere, can take part in creating and maintaining. I don’t want to make too much of this angle on the film; the satirical aspects of both Hostel installments are unmistakably peripheral, even more so than in most horror movies that have such things, and in Hostel, Part II particularly, that subtext lurks quietly in the background just the way it should. Nevertheless, it is worthy of specific notice, simply for being something that the sequel gets conspicuously right in contrast to the atrocious botch-job in the original.

More immediately apparent and ultimately much more significant to the sequel’s success is the treatment of the protagonists. I dearly love seeing somebody learn from their mistakes, and it’s obvious that Roth has done exactly that. You may recall that my most vehement complaints with Hostel were first that Paxton and his friends were such foul, contemptible creatures that it was hard not to see their suffering as at least partially earned, and second that its female characters— victims and victimizers alike— were non-entities to an extent that was downright creepy. (Creepy, that is, like an internet troll calling a woman he’s never met a gold-digging slut who needs a better plastic surgeon, as opposed to creepy in the sense of what you might want out of a good horror movie.) Well, with Beth, Whitney, and Lorna, Hostel, Part II solves both of those problems at a stroke. All three of the girls at the movie’s center are interestingly flawed yet basically likeable, which is pretty much the sweet spot when it comes to writing characters that intelligent viewers are going to give a shit about. And crucially, they have all the things that the women of Hostel lacked: desires, goals, loves, hates, fears, interests— in short, real individuality. Again, I don’t want to overstate the case. These are not deep characterizations in any absolute sense, but they’re sufficiently well layered that Beth, Whitney, and Lorna would each have made a creditable Final Girl in a 1980’s slasher movie (although only Beth fits that specific personality profile at all well). The irony, of course, is that this change for the better will no doubt be lost on many. After all, making the protagonists female pushes Hostel, Part II back into the territory of “horrible things happening to women” that so often gets lazily equated with misogyny by people who find gore movies as a class too all-around objectionable to be granted close attention.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact