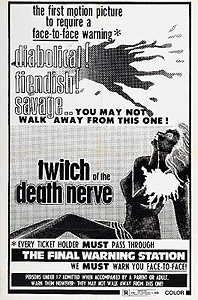

Twitch of the Death Nerve / A Bay of Blood / Bloodbath / Bloodbath: Bay of Blood / Bloodbath: Bay of Death / Carnage / Ecology of a Crime / Before the Fact: Ecology of a Crime / Last House on the Left, Part 2 / Reazione a Catena / Antefatto / Ecologia del Delitto (1971/1973) ***˝

Twitch of the Death Nerve / A Bay of Blood / Bloodbath / Bloodbath: Bay of Blood / Bloodbath: Bay of Death / Carnage / Ecology of a Crime / Before the Fact: Ecology of a Crime / Last House on the Left, Part 2 / Reazione a Catena / Antefatto / Ecologia del Delitto (1971/1973) ***˝

John Carpenter’s Halloween is frequently referred to as the first slasher film. Though it is certainly true that the majority of the slasher movies made in the 1980’s take most of their cues, either directly or indirectly, from Halloween, to call that movie the first not only ignores the existence of The Town that Dreaded Sundown and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (which predate Halloween by two and four years, respectively), but fails to acknowledge many dozens of films that were made in Italy over the course of the 1960’s and 1970’s. I am talking, of course, about the gialli.

The term “giallo” means “yellow” in Italian. The postwar years saw an explosion of pulp fiction in Italy, both original works by Italian authors and translations of novels by foreign writers. The most important publisher of these books, the Mondadori house, used a distinctive yellow cover to give its line brand identity, and in much the same way that the brand name Xerox has become synonymous with photocopy machines regardless of manufacturer, the name giallo expanded to encompass any book that might have fit in with Mondadori’s catalogue. A few of the gialli were stories of supernatural horror, but for the most part, murder mysteries were the name of the game— in fact, there are even giallo editions of Agatha Christie’s books. So in 1964, when the Italian cinema industry began cranking out highly stylized, extremely violent films that were at least nominally mysteries, it was only natural that these new movies should be called by the same name as the books whose popularity inspired them.

What set the cinematic gialli apart from previous filmed murder mysteries was the emphasis— which grew increasingly heavy as the 1970’s approached— on the horrific quality of the murders themselves, rather than on the unraveling of the mysteries surrounding them. And make no mistake, the murders in gialli are most assuredly plural. In the tradition of Ten Little Indians, the gialli presented their murderers as serial killers, and audiences could count on most of the characters winding up dead by the time the credits rolled. The resulting experience was a far cry from the old film noir detective movies. While the old mysteries usually began with a body that was already dead, and followed the progress of the police or private eyes as they dug up clues to the killer’s identity, the gialli confronted their viewers with the spectacle of one graphically depicted slaying after another before finally squeezing the unmasking of the villain— often accomplished accidentally by one of his intended victims— into the final reel. And indeed, in many gialli, the pieces of the puzzle are laid out solely for the audience’s benefit, while the characters themselves never do figure out what’s really going on. Once a psychosexual angle started creeping into the genre to replace the more old-fashioned greed and revenge motives— as early as 1971, though this phenomenon doesn’t seem to have become widespread until a year or two later— the gialli would have only the specific nature of their psychosexual obsessions and their unmistakable visual style to distinguish them from the legions of later American and Canadian films made in the wake of Halloween.

By now you’ve probably guessed that Twitch of the Death Nerve/A Bay of Blood/ Reazione a Catena is a giallo. And because I’ve reviewed gialli before without going into such detail about the genre’s origins and history, you’ve probably also guessed that Twitch of the Death Nerve is somehow important in that history. If so, you’ve guessed correctly. Although it was by no means the first (that honor goes to the same director’s Blood and Black Lace), this movie had a tremendous influence on future films (American ones too, as a matter of fact), and it is also among the best that the genre has to offer. Would you expect any less from Mario Bava, the previous decade’s don of Italian horror, and the man who basically invented the cinematic giallo in the first place?

The film gets off to a somewhat shaky start, with an overlong series of establishing shots of a peaceful bay and its undeveloped, densely wooded shores. The camera finally finds its way past several decaying buildings and into a big, well-maintained old house, where it finds an expensively attired elderly woman (Isa Miranda, from The Secret of Dorian Gray) rolling herself around through the darkened rooms in a wheelchair. As she passes through one of the doorways, a noose suddenly appears in front of her, and is looped around her neck and pulled tight. The old woman falls out of her wheelchair in her struggles, her weight further tightening the noose until she finally strangles and dies. The usual black-gloved man (already a longstanding giallo cliche by 1971) walks into view, but then the camera unexpectedly pans up to reveal his face (he’s Giovanni Nuvoletti). He’s a bit younger than the woman, but well into middle age, and he is as impeccably dressed as his victim. Then something even more unexpected than the revelation of the killer’s face occurs— another Black Glover lunges from the shadows and stabs the murderer to death with a lock-blade knife!

Cut to the office of a lawyer named Frank Ventura (Cristea Avram, from Captive Planet and The Eerie Midnight Horror Show), where Frank has just finished up fucking his secretary, Laura (Anna Maria Rosati). While Laura lounges on the sofa-bed, Ventura is talking about going down to the bay to deal with the legal hassles that have followed in the wake of Countess Federica Donati’s suicide, and the disappearance of her husband, Filippo. We may safely assume these are the two people we just saw murdered in the house by the bay. Ventura, who had been the woman’s attorney, hopes to talk the countess’s heirs into selling their mother’s extensive property, which includes just about all the land on her side of the bay; it’s a prime piece of real estate, and any developer would pay good money for it. In fact, Ventura hopes specifically that he can talk the heirs into selling it to him. Leaving Laura in charge of operations back home, Ventura heads off to the Donati estate.

Meanwhile, back at the bay, we are introduced to some of the countess’s tenants. Paolo Fosatti (Leopoldo Trieste) is an entomologist, and he is quite pleased that Federica is dead and her husband vanished. Apparently, Filippo wanted to open the bay up to development, and had already built a not-particularly-successful nightclub and swimming pool on the land, but with him and his wife out of the picture, there’s now at least some chance of the bay being allowed to retain its pristine natural beauty. Fosatti’s wife (A Hatchet for the Honeymoon’s Laura Betti), meanwhile, is the obligatory tarot-reading crazywoman, who spends most of her time talking about what dire events the cards predict for the future. The third tenant, Simon (Claudio Camaso, from Screams in the Night), is a fisherman who we suspect is trouble, because our first look at him comes while he’s killing a particularly recalcitrant octopus with his teeth.

Ventura isn’t the only person on his way to the bay. The Donatis’ daughter, Renata (Thunderball Bond girl Claudine Auger, who was also in The Black Belly of the Tarantula), and her husband, Albert (Luigi Pistilli, from Gently Before She Dies and The Lady of Monza), have come looking for information about the dead woman and her missing spouse. Like most of the characters in this movie, they don’t quite believe Federica’s death was a suicide. And at the same time, George (Guido Boccaccini) and Bobby (Roberto Bonanni), a pair of local youths, have decided that the bay is the perfect place to take their new girlfriends, Patty (Paola Rubens) and Brunhilda (Brigitte Skay, from SS Hell Camp and Isabella, Duchess of the Devils), for a romantic overnighter.

Naturally, it’s the partying young people who provide our next dose of bloodshed. The four kids are terribly excited to find the dilapidated shell of Filippo Donati’s old nightclub, and Brunhilda is especially pleased to discover that it has a swimming pool. Months of neglect have left the pool unusable, however, so Brunhilda takes off to go swimming in the bay itself. And Bob, apparently, is a bit unclear on the concept underlying this whole trip, because rather than go with her and partake of the skinny dipping action that is sure to follow, he just hangs around making a nuisance of himself for George and Patty. This means that Brunhilda does her swimming both alone and far away from anyone who might aid her if she were to get into trouble, and in what must surely be among the earliest examples of the death-of-the-skinny-dipper set-piece on record, she is pursued and killed after her swimming accidentally turns up the submerged body of Filippo Donati. Brunhilda’s killer then stops in at the abandoned Donati mansion, to which the remaining Expendable Meat has shifted the party, and kills them in a sequence that would later be appropriated wholesale by the makers of Friday the 13th, Part 2.

Filippo’s body later turns up hidden under a pile of cephalopods on Simon’s boat when Renata and Albert come to pump him for information that might shed light on the Donatis’ deaths. (Renata and her husband don’t notice the stiff, of course.) The reason Renata thinks Simon might know something is that her earlier interview with the Fosattis uncovered the tantalizing datum that Simon is Countess Federica’s bastard son. That might complicate the matter of the inheritance, you think? Then Frank arrives, with Laura (who obviously doesn’t follow directions very well) right behind him, and at last real hints of the machinations underlying all the skullduggery at the bay begin coming to light. Albert sees Simon carrying Filippo’s body to the water, and while he runs to get help from the Fosattis, Renata goes to have a look around her mother’s mansion, where she finds the bodies of the young partiers piled up in one of the bedrooms. Suddenly, Ventura appears from a hiding place in the hallway outside, and attacks Renata with a hatchet; Renata, for her part, defends herself ably with a big pair of sharp scissors. When Mrs. Fosatti hears Renata screaming (sound carries a long way in the silence of the bay by night), she sends Albert hurrying back to the Donati place, but no sooner has Albert left than Mrs. Fosatti is killed, obviously by someone other than Ventura. Finally, as the parties with a direct interest in the fate of the bay begin falling to the killer’s machete (or should that be “killers’ machetes?”), we begin seeing just how complicated the tapestry of treachery really is. And by the time it’s all over, the number of survivors will be small indeed, even by giallo/slasher standards.

Bava took a real chance with the structure of Twitch of the Death Nerve. The first half of the film moves extremely slowly, and even once the killing begins in earnest, it’s initially easy to get the impression that there is no actual plot driving this movie. Impatient viewers might very well give up on Twitch of the Death Nerve before it gets around to drawing the lines that connect the seemingly unrelated events comprising the earlier phase of the story. But once it becomes clear why people are dying like flies on all sides, and that every single surviving character shares the same possible motive to kill, the question of who is behind it all becomes deeply fascinating. Twitch of the Death Nerve is thus one of the very few gialli that really works as a murder mystery as well as a straight-up horror film. Whereas in most such movies, the question, “whodunit?” is most likely to be answered with the question, “who cares?,” Twitch of the Death Nerve keeps you guessing, not only in the sense that it is unpredictable, but in the more important sense that it engages enough of your interest that you’ll want to keep trying to figure it all out. In the context of a genre that would ultimately produce films in which the killer’s identity is both known beforehand and completely immaterial to the story, this element of intellectual engagement, added to the attractions of unusually gruesome and effective violence, makes Twitch of the Death Nerve a rare treat indeed. (Beware of Image Video’s version, however. Though it appears to be complete from a content perspective, and is presented in the original aspect ratio, the soundtrack is in horrible condition. The volume varies wildly from second to second, and the audio mix is such that background music, sound effects, and even surface noise are always much louder than the dialogue. Watching this edition all the way through thus takes real dedication and a fast finger on the remote control’s volume buttons.)

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact