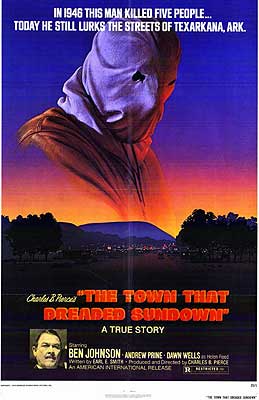

The Town that Dreaded Sundown (1976) **

The Town that Dreaded Sundown (1976) **

When I talk about the development of the slasher movie in the United States, I tend to do so in terms of three specific films: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Halloween, and Friday the 13th. I’m oversimplifying, of course. You’d be missing a lot of the picture without considering the influence of foreign films, especially Italian and Canadian imports like Twitch of the Death Nerve and Black Christmas, and points of continuity can easily be found linking the native US slashers of the early 80’s to previous horror movie cycles stretching all the way back to the silent era. Still, a trend line of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre —> Halloween —> Friday the 13th tells you enough about the genre’s emergence to be useful when concision matters more than the details. We could, however, add a fourth point to the line if we felt like it, and even out the between-films interval to a consistent two years. Indeed, the only reason I normally don’t is because I’m not sure Charles B. Pierce’s The Town that Dreaded Sundown got enough exposure to merit standing in the same company as the other three. It definitely deserves some recognition despite being both fairly obscure and only intermittently interesting, because it demonstrates the pull of those aforementioned overseas influences in ways that the more famous movies don’t. Like an artless hillbilly giallo, The Town that Dreaded Sundown is first and foremost a murder mystery in which it plain doesn’t matter whodunit.

March 3rd, 1946— a Sunday night in the smallish, state-line-straddling city of Texarkana. Linda Mae Jenkins (Christine Ellsworth, of The Savage Bees) and her boyfriend, Sammy Fuller (Revenge of Bigfoot’s Mike Hackworth), are out on one of the rambling, wooded roads that serve the town’s young people as lovers’ lanes when they are attacked by a large man with a pillowcase hood obscuring his face (stunt coordinator Bud Davis). Both kids survive, but only after taking a lot of damage. Fuller and Jenkins were not robbed, nor do they have any known enemies, either singly or as a couple. It therefore seems likely that there was a sexual aspect to the crime, even though Linda Mae was not raped in the usual sense. As the doctor who treats the victims at the local hospital explains to Sheriff’s Deputy Norman Ramsey (Andrew Prine, from Simon, King of the Witches and Grizzly), the girl’s body was bitten all over, especially on the breasts, legs, and back. Neither Ramsey nor anyone else realizes this yet, but the lovers’ lane assault is only the first in a series of horrid crimes that will terrorize Texarkana for the rest of the spring and summer.

The next victims are former Seabee Howard W. Turner (who evidently didn’t merit inclusion in the credits) and Emma Lou Cook (Misty West), the teenaged high school dropout whom he’s been dating for about a month and a half. Exactly three weeks after Linda Mae and Sammy had their bad date curves blown forever, Howard and Emma Lou are set upon and killed under the very same circumstances. Ramsey, patrolling just the right part of the Texarkana hinterland at almost the right time, comes rushing in response to the sound of gunshots, but arrives too late either to save the victims or to apprehend the murderer. News of this second crime spreads panic throughout the city and its environs on both sides of the state line, even as the Texarkana police are forced to admit that they’ve got nothing to go on in the case. Soon Sheriff Otis Baker (Robert Aquino) and Police Chief R. J. Sullivan (Jim Citty) become desperate enough to call for serious backup. It first arrives in the form of Captain J. D. Morales (Ben Johnson, from Mighty Joe Young and Terror Train)— or as the press like to call him, the Lone Wolf of the Texas Rangers. Morales takes over ultimate authority in the investigation, coordinating his own men, the Texarkana police force, cops and sheriff’s deputies from most of the surrounding towns and counties, and even a few FBI agents. But even with all that manpower at his disposal, Morales is unable to sniff out any clues or suspects.

Three weeks later, on April 14th, Ramsey suggests to Morales that there’s a better-than-even chance of another attack come nightfall. Trusting the deputy’s judgement, the ranger orders a massive sting operation set in motion, placing decoy cars manned by two cops apiece (one of them in drag for authenticity’s sake) on each of the roads leading out of town. There’s some extra urgency to the undertaking, too, because April 14th happens also to be the night of a high school prom on the Arkansas side of the city. Prime teenager parking night, in other words. The captain’s strategy sounds like a solid one, and the Phantom Killer is indeed on the prowl tonight. Unfortunately, the cops are lying in wait for him in the wrong place. Rather than haunting the secluded lovers’ lanes on the outskirts of town, the Phantom has come to Spring Lake Park, in the middle of Texarkana. There he ambushes Peggy Loomis (Cindy Butler, of Boggy Creek II: The Legend Continues) and Roy Allen (Steve Lyons, from The Legend of Boggy Creek), who have just come from the aforementioned prom. Peggy plays trombone in the high school band, and… well, you’ll just have to see for yourself how the Phantom incorporates her horn into tonight’s crime. You’d never believe me anyway.

In the aftermath, Morales talks to criminal psychiatrist Dr. Kress (Earl E. Smith, the writer of this very movie) hoping for insight into what makes a man like the Phantom Killer tick. The doctor’s words are not reassuring. The way Kress sees it, the Phantom’s psychology is so abnormal that none of Morales’s usual thinking about motive or whatever applies. He isn’t out for money or revenge or even sexual gratification as Morales understands it. Instead, he kills for the sheer, sadistic thrill of it, and the variations in his routine and technique— beating and biting the first victims, shooting the second, and now that bizarre business with the Loomis girl’s trombone— suggest that he craves novelty in his crimes. Morales therefore won’t even be able to count on the Phantom sticking to a predictable pattern. The killer, meanwhile, will have no trouble tracking or predicting the cops’ moves. Even if Morales becomes much more successful at muzzling the press than he has been thus far, the size of the manhunt, together with the propensity of small-town people to gossip, will ensure that Morales has no secrets from his adversary. Factor in the disruption of false leads like Eddie Ledoux (Joe Catalanotto)— a drifter criminal who creates a brief stir by telling his victims that he’s the Phantom in order to cow them into submitting to being robbed— and Kress puts the odds of Morales ever catching the real killer at two to one against.

Kress turns out to be right, too. Morales and his men never do detect even a hint of rational motive that they could exploit to trap the Phantom, and the killer soon fucks with them further by diverging from his hitherto invariable three-week schedule. And when his next attack does finally come, he hits neither a lovers’ lane nor the city park, but the home of Helen Reed (Return to Boggy Creek’s Dawn Wells, whom most of you probably remember more for “Giligan’s Island”) and her husband, Floyd (another actor who didn’t make the cut for the closing credits). Even when Helen manages to summon help despite being shot twice in the head with a silenced pistol, her heroic efforts don’t result in the Phantom’s capture. An all-night police chase on foot leads merely to the killer vanishing into the swamp to the southwest of the city. The Texarkana Phantom Killer never strikes again after that night, but he’s never caught or identified, either.

The Town that Dreaded Sundown is based on a genuine unsolved murder case, dubbed the Moonlight Murders by the Texarkana press. The film follows the real course of events fairly closely by the standards prevailing among “based on a true story” horror flicks, but there are still plenty of detail differences. The names have all been changed, for starters, although Texas Ranger Captain Manuel Gonsaullas really was nicknamed “Lone Wolf.” The real Phantom’s crime spree began fully a month earlier, in February of 1946. Peggy Loomis’s real-life counterpart played alto saxophone instead of trombone, and far from being used in her murder, the instrument was discovered decaying in its case in the Spring Lake Park underbrush six months later. And unsurprisingly, the dramatic chase into the swamp after the raid on the Reed house is purely the invention of Earl E. Smith and Charles B. Pierce. Where it matters, however, The Town that Dreaded Sundown is an honest enough depiction of events: in the general course of the investigation, in who lived and who died among the Phantom’s victims, in the killer’s basic modus operandi. Even a few remarkably fussy details, like the ages and occupations of the victims, carry over. Most memorably, the Phantom’s appearance— tall, powerfully built man wearing a pillowcase disguise hood— is taken directly from the description that Jimmy Hollis and Mary Jeanne Larey gave to the police. And most importantly, Pierce and Smith keep faith with the central fact that the killer was never brought to any sort of justice, so far as anybody knows.

That commendable devotion to the spirit if not the letter of historical accuracy causes its own sort of trouble for The Town that Dreaded Sundown, however. The viewpoint characters here are Deputy Ramsey and Captain Morales, for the perfectly plausible reason that they’re the only ones apart from the killer who are involved at every stage of the story. The victims were all randomly selected couples who never even met each other, so there was no sense in trying to build the movie around any of them. The model for Dr. Kress came out to Texarkana for one quick consultation before returning to the state prison where he usually practiced. And focusing on the killer would have meant pretending to have some idea who the hell he was. But the cops aren’t satisfying protagonists either, because they never get anywhere close to solving the mystery. Staying true to life thus deprives The Town that Dreaded Sundown of any single, complete narrative through-line. It would have been preferable, dramatically speaking, to invent an identity for the Phantom to which the audience could be made privy even if Morales never uncovered it— perhaps by taking at face value the highly suspect confession of H. B. Tennison, the Fayetteville college student who claimed in his suicide note to have committed the Moonlight Murders. As it is, the movie lacks the cohesion that it needs, even before it’s forced to admit that it was never really leading anywhere.

Smith and Pierce commit another, equally serious blunder, too. Among their unpersuasive strategies for spinning out the running time in the absence of a properly structured narrative is a series of corny gags centered on Patrolman A. C. “Sparkplug” Benson (Pierce himself), the incompetent twit whose efforts to impress Captain Morales invariably end in farcical failure. Benson is basically an update of Ed Wood’s Patrolman Kelton, although if I had to guess, I’d say his reason for being in this movie has more to do with the imbecile desk sergeant in Black Christmas or The Last House on the Left’s Deputy Dumbfuck and Sheriff Shit-for-Brains. Somehow he becomes even more irritating, too, when you take a moment to ponder that this is how Pierce chose to insert himself into the film. Odious comic relief is bad enough, but odious comic relief that’s also a manifestation of director vanity is something else altogether.

In its defense, though, there are moments here and there when The Town that Dreaded Sundown gets its head right and delivers on some of its promise. The character design for the Phantom Killer is unsettling in its simplicity, and Bud Davis plays him with a scary pent-up fury that prefigures Kane Hodder’s interpretation of Jason Voorhees. The attack sequences are all taut, suspenseful affairs, displaying a level of technical proficiency that is sadly not in evidence elsewhere in the film. The trombone scene is so wonderfully screwy, and implies so much about the Phantom’s psychology, that you won’t know whether to laugh or to shudder— and while I’m on the subject of murder methods, there’s something nicely transgressive in retrospect about seeing a slasher killer plug people in the head at close range with a pistol. Pierce makes good overall use of the setting, in ways both obvious and unexpected. No one acquainted with his Boggy Creek Sasquatch pictures will be surprised at his ability to invest a forest clearing or a looming swamp with an effective backwoods horror vibe, but he also capitalizes more craftily than most on the “true story” angle. The Town that Dreaded Sundown makes a cruel mockery of the popular mythology that still adheres to 1940’s small-town America, pointing out that that supposedly kinder, simpler, more moral milieu was no more a stranger to insane serial thrill-killing than the scummy cities of the 70’s. None of that suffices to overcome the directionless script, the cheesy comic relief, or the deleterious effect of so large a cast so short on professional actors, but they do turn The Town that Dreaded Sundown into a movie that any serious horror fan should probably see, even though they probably won’t like it very much.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact