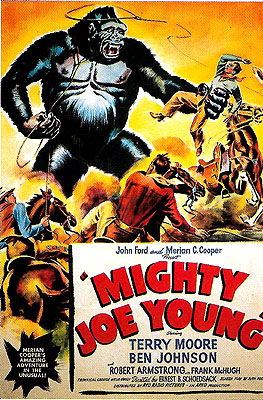

Mighty Joe Young (1949) **½

Mighty Joe Young (1949) **½

It could be said that this film represents a changing of the guard. For most of the first half of the 20th century, if you talked about stop-motion animation, you were basically talking about Willis O’Brien. O’Brien wasn’t the only one using the technique, of course, but the most famous of the old movies employing it were his work. O’Brien was the man behind King Kong, The Son of Kong, and the 1925 version of The Lost World (and for that matter, he also worked on the latter film’s 1960 remake, if only in an advisory capacity), along with several other mostly forgotten movies going all the way back to 1915. But while O’Brien would continue to work in the special effects field throughout the 1950’s, he had by that time been eclipsed by a new alpha-male in the stop-motion pack-- the legendary Ray Harryhausen. What gives Mighty Joe Young significance all out of proportion to its overall merits is the fact that it is the only movie on which O’Brien and Harryhausen collaborated on the effects work. Mighty Joe Young is also the final installment in what might loosely be called the RKO Monkey Trilogy, the three films about oversized gorillas directed by Ernest B. Schoedsack and produced by Merian C. Cooper. (The previous two films were, of course, King Kong and The Son of Kong.) And while it is by no means up to the standard set by the original Kong, it is at least vastly superior to that movie’s embarrassing cheap-jack sequel.

In the simplest terms, this is a fable about a girl and her pet gorilla, and as with all fables, you can rest assured that there will be a moral involved at some point. Our story begins in Africa, where six- or seven-year-old Jill Young (Lora Lee Michel for the moment, but for most of the movie, she’ll be played by Terry Moore, who came from Son of Lassie and who, after some 20 years of respectability, would be reduced to Black Eliminator and Hellhole) gets it into her head one day to trade a few of her toys and her father’s heavy-duty flashlight (the kind cops use to beat you up with) for a baby gorilla that a pair of local hunters have captured. Her plantation-owner father (Regis Toomey, from One Frightened Night and Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea), I hasten to add, knows nothing of this transaction until he arrives home from wherever it is that white plantation owners in sub-Saharan Africa go during the day, and finds said gorilla in Jill’s bed. As he says to Jill when she asks if he’s mad at her, he takes the situation rather well for a man who has learned that his daughter has just acquired a pet ape. But that does not mean Jill is allowed to keep the beast-- a father has to draw the line somewhere, right?

It appears, however, that Mr. Young ought to have used something more along the lines of those huge, smelly markers the kids use to tag the stalls of public toilets to accomplish his line-drawing, because the very next shot has Jill feeding her gorilla (whom she has named Joe) from a baby bottle, while her father looks on bemusedly, feebly trying to reassert his authority to keep his home free from 800-pound apes. But it does no good, of course, and when the screen fills with the image of the Brooklyn Bridge and the legend: “New York, 12 years later,” we know without having to be told that Jill still has her unorthodox pet. So what are we doing on the opposite side of the Atlantic from Jill, her father, and Joe? Why, we’re looking in on the activities of a certain nightclub proprietor by the name of Max O’Hara (Robert Armstrong, from King Kong and its sequel). O’Hara has just decided to spread his wings a bit, and open a new club on the West Coast-- in Hollywood, to be exact. Because of the inherently risky nature of this venture, he wants to make sure that he makes a strong initial showing, and he has come up with what he regards as a fool-proof angle for the new night spot. Riding the wave of public fascination with exotic locales that was then giving rise to the tiki bar, O’Hara plans to give his L.A. club an African theme, and to that end, he has arranged to go on a safari for the purposes of capturing live African animals to give the whole affair the strongest possible air of authenticity. Obviously, one does not attempt to do such a thing alone, and O’Hara hires an Oklahoma cowboy named Gregg (Ben Johnson, who after a long and presumably rewarding career making westerns ended up providing low-cost name recognition to such films as The Deadly Bees, The Town that Dreaded Sundown, and Cherry 2000), along with all of his Oklahoma cowboy buddies, to conduct the actual capture of the necessary beasts. Who would ever have thought that you could rope a lion the way you do a steer?

But that’s just what Gregg and his men do, until they find themselves face to face with an altogether more challenging quarry, a huge, stop-motion gorilla. The fact that this is a stop-motion gorilla should tell you a thing or two, as should the exclamation on the part of O’Hara’s safari guide that gorilla territory is hundreds of miles away. Our expectations are confirmed a few minutes later, when a young woman appears and orders the gorilla (who had been winning the struggle against the cowboys, hands down) to cease and desist. The woman-- the now-grown-up Jill Young-- then launches into Gregg, O’Hara, and the cowboys, demanding to know what in the hell they think they’re doing trespassing on her land and attacking her pet ape. O’Hara and his associates, understandably flummoxed, have no answer capable of satisfying Jill, and they are left standing around looking like fools when the girl storms off into the bush with her gorilla. But O’Hara is not a man to remain stymied for long, and it soon crosses his mind that Jill and Joe are exactly what his L.A. nightclub needs to make the sort of splash O’Hara seeks. He sends Gregg to the Young family plantation (which Jill has been running by herself since the death of her father some six months before) to apologize for the misunderstanding and to try to get her interested in listening to O’Hara’s pitch.

Gregg succeeds, and O’Hara springs into action. He promises her fame, fortune, excitement, a swank new wardrobe-- pretty much everything that a certain other Robert Armstrong character once promised a similar naïve young woman, in fact. And like that other woman, Jill falls for it, hook, line, and sinker. Within days, she, Joe, and Gregg are in L.A., working for O’Hara. The new club is just as garish and tacky and hideous as you might imagine, all caged lions, bamboo walls, and African masks. And then there’s the floor show, which features black dancers dressed as African tribal warriors and musicians playing traditional African rhythm instruments. But the main attraction, of course, is “Mr. Joseph Young, of Africa.” The gorilla makes his big entrance after an introductory speech from O’Hara, rising from a pit in the center of the stage to hold aloft a grand piano on which Jill plays “Beautiful Dreamer,” the song to which she used to put him to sleep as an infant. O’Hara’s crowd is duly impressed, and the promoter assures Jill that her contract will be good for a long, long time.

Of course, that’s pretty much the exact opposite of what Jill wanted to hear. It doesn’t take long before the novelty of being a novelty act wears thin for her, and it wears thin for Joe even faster. The fact that O’Hara has Jill and her gorilla perform ever more exploitative and demeaning acts as the weeks wear on (“Tenth Mammoth Week!” the sign on the front of the club trumpets) doesn’t exactly help the situation, either, and it is during the Tenth Mammoth Week that Jill goes to her employer (with Gregg along for moral support) to announce that she and Joe are going back to Africa. O’Hara is predictably dismayed, but he acquiesces, on the condition that Jill allow him some time to find a replacement act. That seems fair enough to Jill.

But seven weeks later (“17th Colossal Week!”), there’s no sign of any replacement, and Jill is fed up. The show that night is particularly unsavory, involving the audience getting to throw enormous coins at the stage for Joe to try to catch in a commensurately enormous cup, and it gets out of hand when one drunk patron decides it would be funny to throw a bottle at the ape instead. Jill immediately stops the show, returns Joe to his cage in the basement, and goes to talk to O’Hara again. Meanwhile, the offending drunk and his friends sneak downstairs to ply Joe with wine. I guess it seemed funny at the time, but the three men stop laughing when the inebriated Joe smashes out of his cage and destroys the club, relenting only when Jill, O’Hara, and Gregg arrive to bring him under control. Of course, the police arrive too, and they take a rather dim view of rampaging apes.

So, for that matter, does the city of Los Angeles, which secures a court order for Joe’s destruction. Faced with such an incredibly ugly situation, and with the certain knowledge that it’s all his fault, O’Hara goes to Jill with a plan to sneak her and Joe back home to Africa. The rest of the film sees this plan put into action, with an array of blunders and strokes of bad luck to add some suspense, and concludes by giving Joe an unexpected opportunity to redeem himself in the eyes of the law.

Basically, what we’ve got here is an old-fashioned family movie. It’s fundamentally escapist and unthreatening, but it’s not so cloyingly juvenile as to be unendurable for an adult audience. And because it was made in the late 1940’s-- a time when adults were still willing to credit children with a certain amount of resilience in the face of tragedy, before “suitable for children” was taken to mean “unrelentingly, mindlessly upbeat”-- there is up until the very end a legitimate question regarding how it will all turn out. When movies like this are made today, a happy ending is a foregone conclusion. Here, though, there is no such easy assurance, even if everything working out in the end seems to be the likeliest outcome. This genuine uncertainty is Mighty Joe Young’s greatest strength, and makes it easier to look beyond its essential silliness and sappiness to find a surprisingly good-- if childish-- film.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact