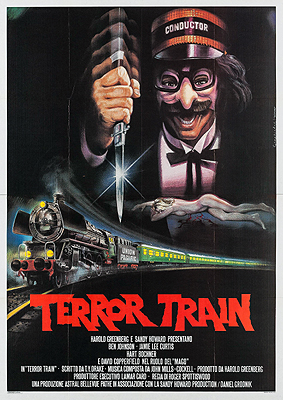

Terror Train (1980) ***

Terror Train (1980) ***

Itís hard to believe, looking back on her career from the vantage point of 2022, that Jamie Lee Curtis was once generally understood to be That Chick Who Makes All Those Horror Pictures. However, thatís mainly because Curtis spent most of the 80ís working very hard to shed that image, and most of the 90ís making sure she wouldnít pick it up again. Although she did some TV work outside the genre around the same time, all six of the theatrically released movies in which she starred between 1978 and 1981 had been fright films. After Halloween II, however, Curtis made a point of turning down any and every gig that involved ghosts, monsters, or butcher knives until 1998ó and even then she mostly stayed out of the scare business apart from legacy sequels Halloween. Just the same, thereís no denying that Curtis (or her agent) knew how to pick a project, even when she wasnít much more than a kid. All but the last of those first six films of hers were worthy examples of their genre. Even Terror Train, probably the most obscure product of Curtisís early scream queen period, has plenty to recommend it. Between the unusual setting, the atypically strong (which is to say, present at all) focus on characterization, and a fairly effective fakeout regarding the killerís modus operandi, this B-side to Prom Night demonstrates how rewarding even the lesser Canadian horror movies of its era can be.

Terror Train is a turn-of-the-80ís slasher movie, so naturally it begins by establishing the killerís motive. Itís that time of the school year when college fraternities conduct the rites of passage whereby their new pledges get a chance to put an end to the ritual humiliations of the hazing process, and at Sigma Phi Omega, that means a great, big party with their counterpart sorority at which the plebs may earn their wings, so to speak, by getting laid. Not all such opportunities are extended in good faith, however. Of particular concern to us just now, thereís an inveterate prankster known as Doc (Hart Bochner, from Apartment Zero and Urban Legends: Final Cut) who delights in entrapping pledges into even greater degradation than was already their lot, and tonight he has his sights set on a dorky kid by the name of Kenny Hampson (Montreal drag performer Derek McKinnon). Doc got that nickname because heís enrolled in the universityís pre-med program, which is distinctly relevant to the nasty trick heís about to play on Kenny. With the help of his fellow frat boy chucklefucks, Mo (Timothy Webber, of Murder in Space and Seventh Son), Ed (Killer Partyís Howard Busgang), and Jackson (Anthony Sherwood, from Eternal Evil and The Vindicator), Doc has borrowed an especially gnarly cadaver from the medical departmentís refrigerators, and smuggled it into a bedroom at the Sigma Phi Omega house. Meanwhile, sorority girl Mitchy (Sandee Currie, of Terminal Choice and Curtains) has persuaded Kenny that Alana (Curtis, from Road Games and Virus), her only slightly less attractive best friend, is willing to go to bed with him, and thereby finalize his initiation into the fraternity. Iím sure you see where this is going. Although that is indeed Alanaís voice whispering seductively from inside the darkened room when Kenny goes upstairs to claim his prize, the bed itself is occupied by the extravagantly dead old lady from the med school fridge. Kennyís mind snaps right in two when his dateís left arm comes off in his hand, and I wish I could say I found it implausible that the only consequence anyone faces for sending him to the nuthouse is an ironclad ban from the school authorities on any further use of Sigma Phi Omegaís peculiar hazing tradition.

Three years later, the boys of Sigma Phi Omega and the girls of Didna Getta Nayma are throwing another party; I confess that Iím at a loss to determine what the occasion might be. The costumes suggest Halloween. The noisemakers, confetti, and snow-covered ground imply New Yearís Eve. But Jacksonís assertion that this will be the last big fete of his and his friendsí college careers doesnít make a lot of sense unless the date is sometime closer to May Day. In any case, Doc has prevailed upon the fraternity president (Greg Swanson) to dig deep into the organizationís recreational budget to hire both a professional magician (real-life stage illusionist David Copperfield) to entertain the revelers and a vintage steam-powered excursion train to serve as the venue for the celebration. While the kids are all piling aboard, a quick bit of conversation between Carne the conductor (Ben Johnson, from Locusts and The Swarm) and his brakeman (Steve Michaels, of Loving and Laughing and Visiting Hours) establishes the literally incredible fact that the antique train has no radio aboard. Then, almost immediately thereafter, weíre shown exactly how that lack of basic fucking equipment is going to bite the passengers and crew on the ass tonight. Ed is the last of the frat brothers to board, thanks to some awkward contrivance separating him from his girlfriend, Pet (Joy Boushell, from Humongous and Cursed), and while heís manhandling his trunk full of class clown props into the baggage compartment (fat lot of good that stuff is going to do him in there!), somebody whose face we donít get to see until after he helps himself to Edís Groucho Marx mask runs him through with the saber we saw him horsing around with a little earlier. The killeró it seems safe to assume that heís somebody affiliated with Kenny Hampson, if not necessarily Hampson himselfó then boards the train in his victimís stead.

Obviously there are plenty more murders to come, but theyíre by no means random. No, this killer plainly knows exactly who among the brothers and sisters was involved in that nasty practical joke on Kenny three years ago, and heís targeting them specifically. Mind you, heíll kill some of the train crew, too, before the night is over, but those are pretty clearly collateral casualties. Also, whenever possible, the killer demonstrates his familiarity with the Hampson Hazing Incident by dispatching his victims in ways that duplicate injuries displayed by the cadaver in the bedó hacking Jacksonís arm off, slitting Mitchyís throat, etc. At first, heís able to conceal his activities by moving the bodies around, so that anyone who stumbles upon one will write it off as a prank when the corpse subsequently goes missing, but there are only so many places to hide that kind of evidence on a train, and Carne is not a stupid man. Alana is no dummy, either, and once she and the conductor compare notes, it becomes obvious what a problem they have on their hands. Of course, Alana canít tell Carne everything she knows without incriminating herself in the Kenny Hampson affair, but she can certainly tell Mo and Doc. The question is, how is Kenny (or his unidentified avenger, as the case may be) evading peopleís notice in a confined space where everybody knows everyone else? Is he just cycling through identity-obscuring party costumes, or does he have some other way of hiding in plain sight even unmasked?

Terror Train was shot back-to-back with Prom Night, for the same independent studio. It should surprise nobody, then, that Prom Night is easily the better-known slasher movie that Terror Train most closely resembles. Both films trade off the hazards of a meandering plot against the opportunities thereby created to develop the personalities of the killerís targets and the relationships among them. Both feature villains with an undeniably legitimate grievance against the people whom they set out to murder, and focus said villainís attention on the actual perpetrators of the wrongs done against them. And both try to soften an inherently unsympathetic roster of potential victims by squarely addressing the issue of their culpability. Terror Train even echoes Prom Night in having a strange, show-stopping interlude late in the second act, although I give David Copperfieldís magic show here the edge over the other filmís Saturday Night Fever-inspired disco sequence on the grounds that it winds up being much more relevant to the story than at first meets the eye. (Incidentally, very clever of the filmmakers to slip an important bit of audience misdirection into a magic show.) Most of all, though, Terror Train resembles its more famous sibling in that Jamie Lee Curtis was just really good at this shit, however little she might have wanted to spend her career as an actress sticking knives into maniacs.

The secret, of course, is that Terror Train also gives Curtis a fair amount to do apart from that. Even before Alana realizes that thereís a killer on the train seeking vengeance for Kenny Hampson, sheís tormented by guilt over her role in Docís hazing prank, and her relationships with all of her old friends save Mitchy have obviously suffered because of it. Most importantly, sheís determined to hold Doc, Mo, and Jackson to some kind of account for what they all did three years ago, if only by forcing them into the same state of guilt-ridden introspection that she now inhabits. That quest creates a lot of ambiguities in Alanaís treatment of the other characters, and while Iím by no means certain that T.Y. Drake and his uncredited co-writers (reportedly Judith Rascoe and producer Daniel Grodnik) intended those ambiguities to be there, I am confident that Curtis recognized them, understood their importance, and played them up wherever she could. For instance, under the circumstances, I think itís appropriate that I was never entirely certain whether Alana and Mo were supposed to be a couple, an ex-couple who have managed to remain friends, or what. What their interactions most strongly suggest is the behavior of lovers who are soon to break up, but havenít yet realized tható which is more than reasonable given the shared misdeed tainting their relationship. It similarly rings true that Alana seems to have forgiven Mitchy in a way that she hasnít yet forgiven the other conspirators against Kenny, herself included.

Letís not overlook, either, that Terror Train does a better-than-average job at its main business. The train itself is a memorable and atmospheric setting, combining in unusual ways the two most desirable characteristics of a slasher movie venue: it features a large but finite selection of places for killer and victims alike to hide and/or become trapped, and itís functionally inescapable until it reaches the other end of the line. Director Roger Spottiswoode makes good use of those assets, too, with an impressive four of the killerís attacks having some real punch to them. In Jacksonís case, itís all about the claustrophobia, as the murderer waylays him in the maximally confined space of the menís toilet aboard one of the club cars. Moís demise during the magic show takes a form that I associate more with espionage thrillers than slasher films, a stealthy stabbing in the midst of a jostling crowd. Doc gets his as the finale to what would probably be remembered as one of the genreís great cat-and-mouse sequences, if only more people had seen it. And the climactic battle between Alana and the killer is a true secret classic, due in no small part to writers and director alike playing exceptionally fair with the physical capabilities to be expected from both parties. Terror Trainís maniac had always relied up to then on the advantage of surprise; without it, heís someone whom a sufficiently feisty young woman could plausibly stand up to, and Alana gives as good as she gets in proper Final Girl fashion. Best of all, this movie is nearly unique in remembering that madness is a weakness, and that a killer driven by trauma will be vulnerable to the effects of post-traumatic stress. I wonít try to convince you that Terror Train belongs in the same company as Halloween and Black Christmas, or even Prom Night and The Burning, but itís up near the head of the next class down, and markedly better than quite a few slasher flicks much more famous than it.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact