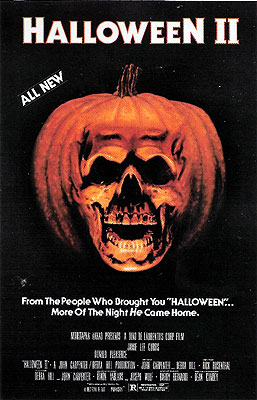

Halloween II (1981) **

Halloween II (1981) **

Halloween had three fathers (along with a mother, Debra Hill, who doesn’t get enough credit). John Carpenter, as director and co-writer, is naturally the person everyone thinks of first, but it was producer Irwin Yablans who originated the premise of a group of babysitters being stalked by a psycho over the course of Halloween night. The third father, Moustapha Akkad, initially provided only the money, but became more intimately involved as the project evolved into a perennial franchise. Anyway, as soon as it became apparent that they had not merely a hit on their hands, but a blockbuster of implausible proportions, Yablans began pushing for a sequel. Carpenter didn’t want to do that, however. He was incubating an idea about a seaside village plagued by vengeful, amphibious ghosts, and he wanted to concentrate on that instead. Yablans agreed, and assumed they had a handshake deal for their next film. But then Avco-Embassy announced John Carpenter’s The Fog as one of their forthcoming pictures— this shortly after Yablans had found himself sitting next to the head of that company on an airplane, and foolishly told him all about the sea-ghost movie he was developing with that Carpenter kid who’d directed Halloween for him. Yablans sued both Carpenter and Avco-Embassy, and the settlement ultimately reached provided that Avco could have The Fog, but Carpenter had to make a Halloween sequel for Yablans. Even then Carpenter cheated a bit, insofar as he wrote and produced Halloween II, again in partnership with Debra Hill, but directed only a few pickup scenes himself. The main body of the film was directed by Rick Rosenthal. All that came as a revelation to me the first time I heard it, because Halloween II truly does play like a movie that someone had to be sued into making. Rarely have I seen a film that so seemed to begrudge its own existence.

Halloween II makes its one genuinely smart move right up front. Rather than attempting to contrive an excuse for Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis again), Dr. Sam Loomis (still Donald Pleasence), or Sheriff Leigh Brackett (a similarly returning Charles Cyphers) to cross paths again with the inexplicably murderous Michael Myers (now played by stunt coordinator and longtime Carpenter associate Dick Warlock) x years later, this first sequel picks up exactly where its predecessor left off. Indeed, it rewinds a bit to show us once again how Loomis saved Laurie at the last moment, only to have the killer escape despite a fusillade of large-caliber bullets that no one should have been able to survive. Then we follow Myers as he ducks into a neighborhood much less affluent than Laurie’s. There he sneaks into one home to steal a new murder weapon, and then into the place next door to stab the girl talking on the phone inside.

Since we know where Michael really is, we also know (instead of merely suspecting) that the identically dressed guy who burns to death in a van explosion after being run over by a police car down the street from the Strode house is just some luckless schmuck. Meanwhile, Brackett, having just discovered that his own daughter was among Myers’s victims, takes the rest of the night off, leaving Loomis in the care of a deputy named Hunt (Hunter Von Leer, from Trancers III and The Unholy Rollers). The two of them hurry over to the coroner’s office after the aforementioned preposterous accident to meet with a dentist about the identity of the charred corpse. The news is inconclusive, but bad; the dentist will need Michael Myers’s full records to be sure, of course, but these look more like a teenager’s teeth than a grown man’s.

As for Laurie, a pair of hunky paramedics called Jimmy (Lance Guest, of Jaws: The Revenge and The Last Starfighter) and Budd (Leo Rossi, from Maniac Cop 2 and Relentless 3) take her to Haddonfield Memorial Hospital, the most understaffed medical facility in all of North America. The only MD on shift tonight is Dr. Mixter (Ford Rainey, of Strange New World and The Naked Zoo), a man who reeks of whiskey even across 37 years and a television set. The hospital also has but one lousy receptionist (Janet, played by Ana Alicia) and one lousy security guard (Mr. Garrett, played by Cliff Emmich, from Girls on the Road and Invasion of the Bee Girls). Head nurse Mrs. Alves (Gloria Gifford) has just two RNs working under her, and one of them— Budd’s girlfriend, Karen (Pamela Susan Shoop, from Empire of the Ants)— is late. Mrs. Alves has to help Jill (Looker’s Tawny Moyer) and Dr. Mixter prep Laurie for surgery on her wounded arm, hand, and ankle herself. It’s just a good thing the Strode girl is apparently one of only two patients in the entire place, outside of the curiously well-stocked neonatal ward.

Yes, now that you mention it, it does sound like I’ve just enumerated a smorgasbord menu of Expendable Meat. The question is how to get Michael to the hospital in order to take advantage of it? It’s the killer’s good fortune that 1978 turned into 1981 while nobody was looking, because in 1981 it’s inevitable that a teenager will happen along sooner or later with a blaring boom box perched on one shoulder. Granted, most Boom Box Boys don’t habitually blare the Plot-Specific News Network, but this one does. With Laurie Strode’s whereabouts thus communicated, Michael proceeds to Haddonfield Memorial, and Halloween II effectively splits into two parallel movies. In one, Loomis and Hunt blunder all over town trying to figure out what makes Myers tick before he can find Laurie and finish her off. And in the other, Michael rampages through the hospital, slaughtering people whom we never really get to know, and can find little reason to care about. As for Laurie, the one gravitational force strong enough to bend those parallel lines into intersecting, she spends most of the running time heavily sedated, having repressed-memory dreams about going to visit a sinister boy several years her senior in some kind of institutional setting. It seems that Laurie and Michael knew each other from somewhere already, and that his campaign of terror against her and everyone he meets while pursuing her isn’t half as extemporaneous as the first movie led us to believe…

Halloween II commits a great many blunders, but giving Michael Myers a motive, however vague and nonsensical, is by far the most serious. What made Myers so terrifying was the awful and senseless randomness of his activities. He murders Annie, Lynda, and Bob for no discernable reason beyond that they’re friends with Laurie Strode, and he targets Laurie for no discernable reason at all. Most other slashers threaten only some specific subset of the population. Jason Voorhees, Norman Bates, Cropsy, Madman Marz, and the Leatherface clan have certain territories that they defend against intrusion. Freddy Krueger, Pamela Voorhees, Hans Beckert, and the Avenger have particular types of victim on which they almost exclusively prey. And of course there are plenty of slashers, like the ones in Prom Night and Happy Birthday to Me, who are out to avenge a specific wrong that was done to them, and who target only those who actually participated in it. Characters like those are essentially modernized versions of the Big Bad Wolf. They’re living admonishments to stay away from the Bad Place, to control reckless adolescent impulses, to refrain from committing the kinds of sin that must be punished unto the nth generation; in a word, they’re avoidable. But Michael Myers, at least in the original Halloween, isn’t the Big Bad Wolf. As Laurie and Dr. Loomis underline for us at the end of the film, Michael Myers is the Boogeyman. You can’t avoid the Boogeyman. If the Boogeyman wants you, he’ll fucking well have you, and there’s no rhyme or reason to what makes him claim one person and not another. Now that Myers does have a reason for pursuing Laurie, he no longer credibly functions as the Boogeyman. After Halloween II, he’s just some nut who hates his family, and so long as you’re not standing between him and one of them, you’re probably okay. If Myers seems smaller in the sequel, it isn’t just because Nick Castle had an inch or two on Dick Warlock.

Giving Michael Myers a motive doesn’t just make him less scary, either. Counterintuitively, it also makes him less plausible. If you look closely at Halloween, you’ll see a very delicate balancing act play out. Depending on the need of the moment, Myers is both man and monster, mortal and immortal, natural and supernatural. The tension can go unresolved there because we’re never given a firm handhold on the killer. All attempts to compute him return a finding of “insufficient data.” Now that we know what Michael wants, however, we can begin to understand what he is, and it becomes inescapably obvious that what he is is totally incoherent. Carpenter seems to understand that, too, because in the very scene where he first hints at the connection between Michael and Laurie, he also squirts out a huge cloud of squid ink about Druids and Samhain and rituals of sacrifice, as if in the hope of obscuring the mortal wound he’s just inflicted on the story. None of it means anything or makes any sense, but neither does it help to reestablish the killer’s aura of terrible mystery.

Frankly, though, some catastrophic fuck-up along those lines was probably almost inevitable once the decision to continue Halloween had been made. Halloween II had at least as many parents in its ineptitude as its predecessor had in deftness, and there was undeniable logic in support of all their mistakes. We can blame Irwin Yablans for demanding a sequel in the first place, but who in his position would really have walked away from that much money? We can blame Carpenter and Debra Hill for not seeing that a second Halloween would make narrative and thematic sense only if the focus were shifted from Laurie to Dr. Loomis, but that would have been box-office folly given what a big name Jamie Lee Curtis had become since 1978. Furthermore, the writer-producers recognized that the early 1980’s were not a hospitable environment for patriarchal monster hunters crusading in support of the status quo. Halloween II, of all movies, needed a Final Girl. A similar calculus lay behind the decisions to quicken the pace and to inflate both the body count and the gore quotient at the drastic expense of character development. Carpenter and Hill cannily reckoned that anyone who’d go see Halloween II in 1981 was really looking for a new Friday the 13th, and that the secret to profitability lay in palely imitating Halloween’s palest imitators. A depressing and cynical notion, to be sure, but not one that I’m prepared to refute. Finally, Halloween II featured a new major player behind the scenes, one whose involvement in a Hollywood project rarely bodes well for it. To bankroll the sequel, Yablans and Akkad joined forces with none other than Dino De Laurentiis. It’s to him, I’m certain, that we can most fairly attribute the signs, pervasive throughout Halloween II, that a great deal more money has been spent to a great deal less effect. Consider the ludicrously quiet and empty Haddonfield Memorial Hospital, cobbled together in the editing room from several widely dispersed shooting locations, none of which turned out to be suitable in practice, and each of which added significantly to the film’s gestation time in its own way. Consider also the remix of Carpenter’s iconic score, which adds several layers of new and more complex instrumentation, yet succeeds only in sounding cheap and shitty. These are just the sort of things that always happened whenever Dino climbed aboard. In the end, I think the most honest and accurate assessment of Halloween II is Yablans’s own. Upon seeing the finished product, he deemed it hacky and pedestrian, yet at the same time figured it was almost miraculous that it turned out even as well as it did.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact