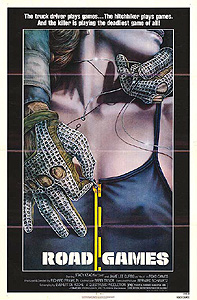

Road Games (1981) ****

Road Games (1981) ****

Just this past update, I was talking about the Auteur Theory, and I mentioned that I thought it needed expansion to encompass personnel other than directors who might occasionally impress an authorial stamp upon the films they work on. I suggested producers, cinematographers, art directors, and special effects maestros as people whose positions could allow them to snatch pride of place away from a weak or stylistically modest director, and some of you might have thought it odd that I said nothing at the time about the possibility of auteur screenwriters. I left them out of the discussion for a reason, however. Normally, screenwriters operate far enough from the thick of the action that it’s difficult to imagine their voices being the dominant ones in a completed film. After the executive producer insists on casting an action hero to play an everyman; after the line producer orders the original climax scrapped on financial grounds, and the scenes of a whole shooting day dropped to bring the production back on schedule; after the stars have balked at lines they felt were out of character or contrary to their public personas; after the director has done all the thousand things that directors do— what, realistically, could remain of the screenwriter’s original vision? But now Everett De Roche has got me thinking that maybe a truly exceptional screenwriter can seize the auteur spotlight after all. It isn’t just that every De Roche-scripted movie’ I’ve seen so far has been great or near-great, although that’s certainly true. It’s that they’re all great or near-great in a particular, characteristic way: smartly nuanced, with a conspicuously astute sense of character and a pronounced tendency to come at a premise from oblique angles. Even in Razorback, where Russell Mulcahy’s MTV-trained stylization is the first thing you notice, the subtler De Roche touch is apparent to the practiced eye. If we take doing the unexpected with the obvious to be the most salient trait of his writing (and after watching this movie, Patrick, and Long Weekend in rapid succession, that seems a fair enough assessment to me), then Road Games might be the De Rochiest film of all. The premise behind Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window had received one hell of a workout during the past twenty years (Dario Argento in particular would barely have had a career without it), but who except apparently De Roche would ever think to reset that premise on a transcontinental trucking run from Sydney to Perth?

Patrick Quid (Stacy Keach, from The Mountain of the Cannibal God and The Ninth Configuration) has led an adventuresome life, serving aboard a warship in the Persian Gulf, smuggling guns in Sudan, and now freelancing as a long-haul trucker— excuse me, truckie— in Australia, his only companions the volumes of poetry he carries with him in his cab and a tame dingo by the name of Boswell. After a grueling several days on the highway, Quid would like nothing better than a proper night’s sleep in a hotel bed. No sooner has he pulled into the parking lot of a promising-looking motor lodge, however, than he gets a call on the radio from one of his regular clients looking to hire him for an urgent job. There’s a meat-packers’ strike going on in Perth, and grocery stores there are desperate for something to sell at their butcher counters. Indeed, they’re so desperate that Patrick is able to finagle double his usual rate to pick up a trailer full of butchered hogs at 5:00 the following morning. Unfortunately for him, those negotiations take long enough for somebody else to snag the motel’s last vacancy, forcing Quid to sleep in his truck yet again.

As it happens, Patrick sort of knows the guy who took “his” room (played by Grant Page, of Stunt Rock and The Man from Hong Kong). That is, he recognizes the other man’s green van as one he saw on the road earlier in the day. For that matter, he also recognizes the girl accompanying Van Guy (Angelica La Bozzetta) as a hitchhiker whom he considered picking up despite regulations to the contrary. Quid doesn’t think any more of it after he beds down in the cab of his vehicle, but the repercussions of that sort-of encounter are going to follow him all the way to Perth. You see, Van Guy is a serial killer, and the hitchhiker is to be his next victim. He cuts the girl up after garroting her with a guitar string (a “G,” it looks like— must have damn near taken her head off all by itself!), then bags up the parts for piecemeal disposal. The first fragment goes out with the motel’s trash, which is how Quid starts to get involved. When Patrick lets Boswell out for his morning piss, the dog heads straight over to the garbage, as if he smells something out of the ordinary inside. Then, while he’s puzzling over his pet’s behavior, Quid notices somebody up on the second floor watching the trash intently until the sanitation department comes to collect it. Patrick won’t understand what he just saw for some time yet, but it does strike him as odd that anyone would be up at that hour, just to make sure the garbage men were doing their jobs.

A funny thing about long road trips across mostly empty country is that you tend to encounter the same fellow drivers again and again along the route. Quid “meets” most of the recurring cast for this haul within about the first hour after taking possession of his cargo. There are the newlyweds in the white Microbus. There’s the guy whose station wagon is packed full to the ceiling with various species of sporting balls. There’s the sensible-looking family in the sensible sedan, the adult members of which Patrick dubs Fred and Frita Frugal (Colin Vacao and Marion Edward). There’s “Captain Careful” (Bill Stacey, of The Box), a middle-aged man towing a sailboat on a rickety trailer behind a car nowhere near powerful enough for such work. There’s “Sneezy Rider” (Robert Thompson, from Thirst and Patrick), the pink-clad motorcycle enthusiast whom Quid sees for the first time as he’s tossing a used tissue to the side of the road. And of course there’s the killer in the green van. Most ominously, in light of the latter’s continued presence, there’s also a pretty, young, female hitchhiker (Jamie Lee Curtis, of Halloween and Halloween II). The green van is nowhere to be seen the first time Patrick passes her, but surely it’s only a matter of time.

Rather unexpectedly, the first of that bunch whom Quid meets face to face is Frita Frugal, who forces him to stop with a rather ingenious trap that isn’t worth the effort it would take to describe it. Her real name, it happens, is Madeline Day. Evidently the family stopped for some reason (I’m guessing bathroom break), and her scatterbrained husband, Floyd, drove off without her. It’s a curious coincidence, them crossing paths like this, because Floyd Day is an accountant for the very company whose labor-relations difficulties have turned the citizens of Perth into involuntary vegetarians of late. In fact, the Days are on the run from that situation, the strikers evidently believing that Floyd’s records contain information useful to their cause. It therefore puts Madeline on her guard a bit when she finds out what Patrick has in his trailer. What ultimately sends Mrs. Day screaming away from the truck, though, is the outcome of a guessing game she and her semi-willing chauffeur play to fill the hours and miles between them and the roadhouse where they’ve agreed she gets off. It’s a variation on Twenty Questions focusing on objects of interest either inside the vehicle or in the surrounding landscape, and on her final turn, Madeline picks something from the roadside scenery that Patrick didn’t notice at all: the man with the green van digging a hole atop a low hillock beside the highway. Earlier on, it had come up in conversation that the news media in New South Wales had been abuzz recently over the activities of a hitchhiker-killing maniac. When Patrick gives up guessing, and Madeline tells him what she saw out her window, a whole bunch of things suddenly snap into place: the green van and the hitchhiking girl at the motel last night; the half-seen person on the second floor standing vigil over the motel’s garbage; the bag that Boswell wouldn’t stop sniffing. At once, Quid pulls over, and jumps out of the truck to look back down the highway for himself. Yep. That’s the green van, alright. And Quid’ll eat his hat if the driver isn’t disposing of another piece of that girl. He doesn’t explain very clearly what has him so agitated, though, and Mrs. Day quickly comes to believe that she has fallen into the Hitchhike Killer’s clutches. Patrick’s efforts to quiet her achieve no better than to get her fleeing in a direction that won’t carry her over the sea cliffs to the south, but I guess that’s something, anyway.

Shortly thereafter, Quid sees that other hitchhiker again, and this time he’s sufficiently worried about the killer on the loose that he stops to give her a ride. Her name is Pamela Rushford, and she’s a diplomat’s daughter who grew weary of the upper-crust lifestyle. She’s been on the road about as long as Quid has on his last couple of runs, seeking excitement but not finding very much so far. Pamela also recognizes Patrick’s truck as one that failed to stop for her twice already, so she’s naturally curious about what made him change his mind. That gets them talking about the guy in the green van, and— well, here’s that excitement Pamela was looking for, right? She and Patrick find themselves busy with a new pass-the-time road game, figuring out the psychology of the killer. And as they grow more certain of their conclusions, figuring him out gives way to devising some means of trapping him and bringing him to justice.

There’s one rather big problem with that, however. Quid’s full name is painted, big as life, on the driver’s-side door of his rig, and that was the name the killer gave the motel counter clerk when he checked in with his latest victim. That means there’s a paper trail linking Quid to her disappearance, and Patrick has been unwittingly making a patsy of himself ever since. Hell, just giving Pamela a lift is incriminating, since it associates him with step one of the killer’s methodology. Now think about what Madeline Day is going to say whenever she reaches that roadhouse. Think about how Captain Careful is going to edit his version of the story when he has to explain to the highway patrol how he tried, in a fit of road rage, to run Quid off the highway, but got the worst of the engagement. Think about what Sneezy Rider is going to say about the time Patrick corners him in a gas station bathroom under the mistaken impression that he’s the killer, and then tries— tries, mind you— to steal his bike after the real psycho abducts Pamela and races off with her. Worst of all, think about how it’s going to look when the murderer recognizes Quid’s refrigerated trailer as the perfect place to stash some more of his leftovers.

As someone who has often expressed limited tolerance for Brian De Palma’s dedicated counterfeiting of Hitchcock, it feels a little weird to be so utterly smitten by Road Games. It’s at least as blatant a riff on Rear Window as Body Double, and it doesn’t have the vast, overwhelming perversity of that movie to make up for it. So why is it that Road Games doesn’t provoke from me that, “Yeah, okay— so you love Hitchcock… Now what else have you got?” reaction that colors even my most favorable assessments of De Palma’s early-80’s thrillers? Part of it is simply how far the story has been transposed from its original setting. Moving the locus of action from an apartment complex to the open road introduces a degree of dynamism that few other “somebody accidentally witnesses a murder” films can match, while paradoxically maintaining that boxed-in feeling that was so important to Hitchcock’s prototype. It’s still the protagonist’s need to occupy his mind while his body is confined to quarters that draws him into conflict with a killer, but now there’s a much stronger element of randomness to when, where, and how the two combatants cross paths. It’s also significant that Patrick and Pamela, as played by Stacy Keach and Jamie Lee Curtis, are Americans abroad; it adds overtones of culture clash and xenophobia to the scenes where Quid discovers how his actions since leaving the hotel have been digging him deeper into a hole he never knew he was in. And to draw the comparison with Body Double once again, we shouldn’t discount the way Road Games, like the latter movie, pulls in influences other than Rear Window. But whereas De Palma used ideas drawn from other Hitchcock films to complete the recipe, Road Games turns instead to Duel. What’s more, it stands its Duel riffs on their heads, pitting a trucker just trying to do his job against a psycho in a much smaller and less powerful vehicle. Quid would have the upper hand in a stand-up fight (in fact, we’ll see at the end that that’s true even when he and the killer are outside their rides), but that’s not the game Van Guy is playing.

On a more general level, Road Games is also noteworthy for defying the viewer’s expectations and satisfying them at the same time. It’s easiest to see what I’m talking about if we look at a sequence during the climax, after Quid has caught up with the killer, and the police have caught up with Quid. Van Guy leads Patrick down an alley just barely wide enough for his truck, seeking to force him out for a man-to-man confrontation, only to find that the alley is so narrow as to trap Quid in his cab. A clean getaway would be he next best thing to a showdown, but now the killer finds that his van won’t start. Quid, meanwhile, is stuck where he is because of a catwalk between the two buildings, which cuts across the alley at a height about a foot and a half lower than the top of his trailer. And the cops, following too closely to see that catwalk coming, and therefore not expecting Quid to stop, have got their bumper tangled up in his. The next few minutes are given over to the killer wrestling with his ignition, Quid forcing his truck against the relatively pliable sheet metal of the catwalk in the hope of punching through it, and the police gunning their engine in reverse to free the car from Quid’s back bumper. In other words, we have here a motor vehicle chase in which none of the three participants are able to move! And yet director Richard Franklin’s skillful application of the latest action movie staging techniques makes it as thrilling as anything in Mad Max. That kind of inventiveness in doing things sideways doesn’t come along very often, but it’s all over Road Games.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact