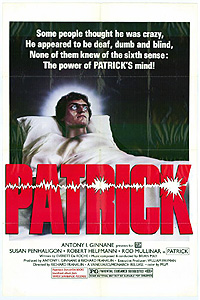

Patrick (1978) ***Ĺ

Patrick (1978) ***Ĺ

Evidently Australian filmmakers know how to play the blockbuster cash-in game, too. Youíll know at once which blockbuster is being cashed in on here if I point out that Patrick is a film about a psychokinetic teenager, and that the one-word title is the kidís first name. But while Patrick plainly owes its existence to the success of Carrie, it is nothing so simple as a direct rip-off. Rather, itís more of an Omen-Exorcist situation, in which the coattail-rider maintains a strong independent personality even though it makes no effort to conceal that it never would have been made if not for the earlier movie. In Patrick, the deadly psionic is a boy, obviously, which changes a great deal all by itself. But more importantly, heís also a psycho from the outset, and he manages to cause all his paranormal havoc from the depths of a three-year coma.

Patrick (Robert Thompson, of Road Games and Thirst), like a lot of horror movie villains, has a strained relationship with his mother (Carole-Ann Aylett, also in Road Games). Dad is no longer in the picture, and the idea of Mom keeping up an active sex life anyway nauseates and infuriates the boy. One night, as Patrick sits in his bedroom, listening through the walls to the sound of his mother making love to her newest paramour (Paul Young, from Death Watch and Mad Max), he decides that he can stand no more of her lascivious ways. He fires up an electric space heater, and once the device is running full blast, he barges into the bathroom, and tosses it into the tub to which Mom and her lover retried after exhausting the immediate possibilities of the bed. We donít get to see just what happens next, but from the look of things, Patrick finds the reality of homicide rather more stressful than he anticipated. The police find him in a catatonic state, which eventually deepens into a proper coma, and they never do guess that the boy was the perpetrator of his motherís murder, instead of just a witness to it.

Three years later, Patrick resides at a nursing home called the Roget Clinic. In one sense, heís the star patient, because the eponymous Dr. Roget (Robert Helpmann) sees him as possibly the key to explaining how death works at the cerebral level. You see, at the hospital where he was initially treated, the doctors determined that there was nothing going on in Patrickís brain beyond a few purely autonomic processes. His whole cerebral cortex read as dark as a city skyline during a power failure, and as Roget himself puts it, if he ever does regain consciousness, heíll probably be on about the same intellectual level as a penicillin culture. In effect, Patrick is dying in slow motion, and the doctor is determined to let the process draw out in the hope of extracting whatever clues to the nature of death he can. After all, the patient himself is in no position to complain.

Now you might think that a comatose patient would be no problem for a staff accustomed to dealing with intractable Alzheimerís cases like Patrickís neighbor, Captain Fraser (Thirstís Walter Pym), but all the nurses at the clinic harbor a nearly superstitious dread of the unconscious boy. The head of the staff, Matron Cassidy (Julia Blake, from The Day After Halloween and Donít Be Afraid of the Dark), wonít so much as set foot in room 15 if she can help it. But as we see from the perspective of the newly hired Kathy Jacquard (Susan Penhaligon, of The Land that Time Forgot and The Uncanny), the nursesí unease around Patrick is not unfounded. There are his eyes, for one thing. For some unfathomable reason, Patrick entered his coma with his eyes bulging open, and he hasnít blinked once in three years. As a practical matter, that just means that one of a nurseís duties is to keep the boyís eyeballs clean and damp, but itís hard to be practical with that ineffably malevolent stare on you all the time. Equally creepy in its subtler way is the condition of Patrickís body overall. Normal coma patients waste away as their muscles lie inert, but not this one. Heís as toned and sturdy today as he was when the cops wheeled him out of his motherís flat. Also, Patrick spits. Dr. Roget says itís some sort of reflex action, but any of the girls whoíve been subjected to one of his thick, mucous gobbers will tell you that the precision of his aim and timing argues differently. They canít explain how a patient who registers no externally measurable brain activity can commit acts of deliberate malice, but thatís exactly what makes the spitting so damned eerie. Finally, thereís the stuff too quietly weird to acknowledge, let alone talk about, like the way Patrickís window wonít stay closed, or the persistent unreliability of the wiring in room 15, which seems somehow to come and go in response to what youíd assume were Patrickís moods if he were capable of having any. Even so, Kathy herself isnít frightened. If anything, she feels sorry for Patrick, shunned and resented by his caretakers, even if the lad himself is unable to perceive their treatment of him.

Patrick also sparks Kathyís curiosity, but neither Dr. Roget nor Matron Cassidy wants to answer any of her questions. Cassidy, in fact, seems to regard the new girlís interest in the Roget Clinicís creepiest patient as a challenge to her authority and a personal affront. Luckily, Kathyís coworker and self-appointed new best friend, Paula Williams (Pacific Bananaís Helen Hemmingway), is also pals with neurologist Dr. Brian Wright (Bruce Barry, from Libido and Plunge into Darkness). Paula mainly wants to play matchmaker for Kathy and Brian, but the two of them can just as easily talk shop instead after Paula makes their introductions. Kathy therefore goes with Paula to a party at Brianís house, and while picking Wrightís brain for insights into the intricacies of persistent vegetative states, she witnesses something very odd. Brian is swimming in his backyard pool as they chat, and he suddenly starts behaving as if something had hold of him. Wright could swear something does, too, except that thereís no one and nothing in that end of the pool with him. Kathy helps him struggle free of the water, but she can offer no guesses as to what just happened. Still, a near-death experience is one hell of an ice-breaker, and the pair start spending a lot of time together. That, by the way, is not without intricacies of its own, because Kathy is still technically married to Ed Jacquard (Rod Mullinar, of The Pyjama Girl Case and Dead Calm). Since Edís possessive attitude is one of the reasons the Jacquards are riding the Splitsville Express in the first place, itís only natural that Kathy thinks immediately of her husband when she and Brian return from a night out together to find her apartment thoroughly trashed.

Ah, but maybe Ed isnít the only jealous man in Kathyís life. Not long before the wrecking of her flat, Kathy made a rather shocking breakthrough with Patrickó she got him to communicate. Nothing as dramatic as waking up and speaking, or even a wiggle of his big toe, but he turns out to have at least enough awareness of the world outside his skull to answer yes/no questions with short puffs of air, like a less phlegmy version of his familiar spitting behavior. Evidently Patrick notices and appreciates Kathyís willingness to regard him as still a human being, but he refuses to demonstrate his new trick for anyone else at the clinic. What might that have to do with vandalized furniture, you ask? Well, a few days after her discovery, Kathy is typing up clinic correspondence during her shift in room 15, but the words that wind up on the page arenít the ones she means to transcribe from her superiorsí handwritten notes. Indeed, what she types would make absolutely no sense unless she were taking subconscious dictation from Patrick instead. And in fact the comatose boy soon reveals the ability to control a typewriter even without Kathyís brain and body to act as an interface. We know, even if Kathy doesnít, that Patrickís views on women and their sexuality are exceedingly unhealthy. We also know, along with Kathy this time, that Patrick has developed some degree of affection for her. Put the two together, assume that the comatose boy somehow knows about Brian Wright, and doesnít a punitive psychokinetic tantrum in Kathyís flat start looking like a distinct possibility? Patrickís mental powers could also account for the inexplicable force holding Wright underwater at the party that night, since Brianís behavior up to then was sufficiently ungentlemanly for Kathy to take offense at it, even if she subsequently changed her mind about the neurologist.

Brianís not the only one in danger, though, if Patrick has decided to appoint himself defender of Kathyís honor. Ed has lately resolved to put everything he has into salvaging the marriage, and although his methods remain often gallingly paternalistic, itís plain enough that his motives are sincere and laudable. That makes Ed a rival for Patrick and a target for his white knight complex, which clearly spells trouble should Ed ever come within Patrickís range of influence. Kathy herself has plenty to fear, too, since weíve already seen how jealousy can set Patrick off. As it happens, though, what first drives Patrick to serious violence has nothing to do with his feelings for his favorite nurse. Patrick is well aware of how the rest of the clinic staff sees him, and he correctly believes that some of his keepers would be more than happy to add an overdose of sedatives to his IV one of these days. He also recognizes that Kathyís interest in him is making his enemies at the clinic very nervous. The time seems right, in other words, for a little preemptive self-defense.

The most impressive characteristic of Patrick is how utterly its own thing it manages to be without ever attempting to disguise its origins as a Carrie cash-in. Patrick is a completely different sort of underdog monster than Carrie White, despite having almost exactly the same repertoire of paranormal powers. Carrie, to start with, was an underdog first, and became a monster only because she had no other way out of the cramped little box sheíd been stuffed into all her life. Patrick was always a monster, even before he acquired the ability to move objects around with his mind, and the only reason heís an underdog now is because being a monster turned out to have unexpected side effects; if he hadnít killed his mom, he wouldnít be in that coma today. The two movies play the sympathy card differently, too. Carrie is a shy, quiet girl who obviously deserves better than her lot in life, and she would never think of issuing a blanket psychokinetic beat-down to her entire town if only people would just leave her the fuck alone. What happens at the end of her story is as tragic for her as it is for everybody on the receiving end, and we end up feeling sorrier for Carrie than we do for most of her victims. Matricide, on the other hand, is not the kind of thing that endears one to a person, so itís difficult to share Kathyís compassion for Patrick even if we somehow manage to look past the CREEPY STARING EYEBALLS and the deadly paranormal pranks. Nevertheless, the fact remains that the people charged with caring for Patrick in the nursing home have been treating him as a subhuman, inanimate thing ever since he arrived. To Roget, heís nothing more than a lab animal. To the nursing staff apart from Kathy, heís a sideshow freak whose act theyíre obliged to watch as a condition of their employment. And to Matron Cassidy, heís a mocking reminder of how little modern medicine can do in the face of really serious illness. All of them are counting on, hoping for, or seeking opportunities to engineer Patrickís death, and they donít even know about his crime! Itís far more morally confusing a situation than Carrieís justifiable but wildly excessive vengeance, and as you all know by now (or at least those of you who are regulars around here), I tend to like my horror movies morally confusing.

Another neat thing in this movie is the way it misdirects your character expectations. Take Kathyís competing love interests, for starters. Brian seems like a decent guy for an unapologetic playboy, while Ed gives every indication of being a total shit. Yet when things really turn ugly, Ed becomes a genuinely supportive (if not especially effectual) ally, while Brian leaves Kathy to her own devices. And her most useful ally of all turns out to be Dr. Roget, who spends practically the whole movie up to then doing everything he can to prevent her from spoiling his fun by demonstrating that Patrick isnít really brain-dead after all. The most surprising character, though, is Matron Cassidy, whom youíll immediately peg as Patrickís answer to Mrs. White. She may look like a nun in her habit-like Commonwealth nurseís uniform, and she may devote most of Kathyís job interview to accusing her of all manner of sexual perversions, but it isnít devotion to God that makes the matron so stridently nasty. In fact, Cassidyís hatred of Patrick in particular seems to stem in part from the corrosive effect that three years of exposure to him has had on her faithó not only her faith in divine or cosmic justice, but her faith in the value of her profession as well. The whole rest of her career, meanwhile, seems to have killed off any faith she might ever have had in humanity.

Finally, Patrick is another one for my imaginary course on womenís issues as seen through the prism of exploitation horror movies. It feels absurd to say that about a film produced by infamous sleaze-peddler Anthony Ginnane (the guy who had the makers of Not Quite Hollywood interview him in a strip club), but itís true. Presumably much of the credit belongs to screenwriter Everett De Roche, who penned scads of deceptively smart Australian grindhouse pictures over the years, including Long Weekend, Road Games, and Razorback. But whoever deserves the tip of my hat (or my luchador mask, as the case may be), the point is that Patrick has much to say about gender relations in 1970ís Australia, and some of its comments remain broadly generalizable even today. The key point is that each of Kathyís rival love interests personifies a common profile in masculine bad behavior. Ed exemplifies possessiveness and entitlement, with his frequent spying, his habit of letting himself into Kathyís flat uninvited whenever he pleases, and his apparent belief that the marriage failed because he didnít buy her the correct stuff. Brian is all about aversion to commitment, in a way that applies beyond just his romantic partners. Although he cooperates for a while with Kathyís efforts to prove that thereís more going on inside Patrickís skull than anyone thus far has been prepared to accept, Wright drops her in the most insulting manner at the first sign of genuine risk to his own position. And Patrick, of course, represents the Madonna-whore complex and macho protectiveness run amok. Now have a look at Kathy herself. Not only does she come in with the first big wave of horror movie heroines who act as their own rescue squads, but she puts a stop to Patrickís paranormal killing spree precisely by exploiting his pathological sexism and the insecurities that go along with it. That is, Kathy wins in the end because sheís figured out what makes creeps tick, having had ample opportunity to study them in various permutations all movie long. Itís one of those moments when subtext suddenly becomes text, and you start to wonder whether things youíd assumed to be mostly accidental might have been done with conscious purpose after all.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact