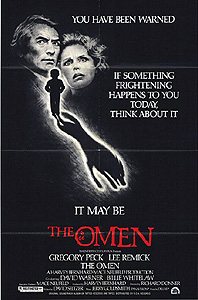

The Omen (1976) ***Ĺ

The Omen (1976) ***Ĺ

The bulk of the Satanically-themed horror films that came in the wake of The Exorcist are more or less forgotten today, and with very good reason. Most of those movies were merely direct copies, and The Exorcist leaves little room in the average viewerís memory for the likes of Abby or Malabimba. There are, however, two later products of the 70ís Satan-rush that have fared rather better than that over the years. One of theseó The Amityville Horroró honestly isnít a whole lot better than your average Italian Exorcist clone, but it at least has its own distinct personality, and it did well enough at the box office to spawn a whole lineage of ever-shittier sequels. The otheró 1976ís The Omenó was a different story. Like The Exorcist, The Omen was made on quite a big budget, for a mainstream studio, and like The Exorcist, The Omen was a sufficiently prestigious project to attract a fair number of name actors to its casting call. The two movies are also similar in that they both revolve around a child, but are neveró not even brieflyó presented from that childís point of view. Indeed The Omenís Damien Thorn is even more of a cipher than Regan MacNeil, but there is a very good reason for his placement off to the side of the filmís main focus. Whereas the driving force of The Exorcist is the effort to rescue Regan from the demon that has taken up residence inside her, Damienís relationship with the powers of darkness is not one of mere possession. Little Damien Thorn is the spawn of Satan himself.

The year is left wisely unstated, but the date is June 6th, and the time is 6:00 am. An extremely wealthy American named Robert Thorn (Gregory Peck, of Marooned and The Boys from Brazil) arrives at a Catholic hospital in Rome, where Father Spaletto (Martin Benson, from Cosmic Monsters and The 3 Worlds of Gulliver), the administrative head of the maternity ward, has some bad news for him. Spaletto informs Thorn that his child died scant moments after his wife, Cathy (The Medusa Touchís Lee Remick), gave birth to him. Robert is stunned, and he expects that his wife will be outright devastated. Thatís when Father Spaletto makes a most unorthodox proposal. Evidently there was another tragic birth at the same time as Cathy Thornís, but in this case, it was the mother who did not survive. Since Cathy was pretty well out of it when her own son was born, and thus has no idea yet that the child is dead, Spaletto could perform a little under-the-table switcheroo, and the Thorns could go home with the orphan that very night, leaving Cathy none the wiser. There are times when it sure does help to be rich as fuck, huh?

Five years later, an old college buddy of Thornís has been elected President of the United States, and Robert himself has been appointed ambassador to Great Britain. He and his family move from Rome to London, where they set themselves up in a dwelling thatís more a palace than a mere mansion, and Cathy hires a local girl named Holly (Holly Palance) to serve as a governess to young Damien (Harvey Stephens). Everything seems swell in Thornland until the boyís fifth birthday. That afternoon, right in the middle of the birthday party, Holly hangs herself from the roof of the mansion after yelling happily to Damien that ďItís all for you!Ē Photographer Keith Jennings (David Warner, from Nightwing and Tron) accounts for only a small part of the paparazzi presence at the event, and the nannyís startlingly public suicide is all over the papers within 24 hours.

Reporters arenít the only ones who start following Thorn around after that, however. A day or two later, a priest from Rome who calls himself Father Brennan (Patrick Troughton, from Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger and The Gorgon) comes to see Robert at work with what sounds at first to be blackmail on his mind. Vehemently urging Thorn to ďaccept Christó drink His blood,Ē Brennan goes on to say that he was at that hospital five years before, and that while he was there, he saw the mother of Robertís child. And make no mistake, Brennan knows very well that Cathy Thorn is not Damienís real mom. Thorn has the embassy security guards throw Brennan out before he can finish telling Robert just who the mother was (ďItís mother was a jóĒ is all he gets out before the guards burst in), but regardless, the ambassador goes home that evening a troubled man. Keith Jennings is troubled, too. He happened to snap a few pictures of Brennan on his way out, and upon developing them, he notices a strange dark streak transfixing the priestís body in each oneó a streak remarkably like the one that seems to encircle Hollyís neck in the photo Jennings took shortly before she hung herself.

Speaking of nannies, the Thorns have just acquired a new one. Her name is Mrs. Baylock (Billie Whitelaw, from The Flesh and the Fiends, who was also the voice of Aughra in The Dark Crystal), and she certainly seems qualified. The thing is, though, that neither Robert nor Cathy hired her. The coupleís minds are set at ease when she explains that she works for the same agency as the unfortunate Holly, but I wouldnít be too sure of that. Her manner is strongly off-putting, as is her insistence upon being alone with Damien for their initial meeting. So, for that matter, are the first words she speaks to the boy upon stepping into his bedroom: ďHave no fear, little one. I shall protect thee.Ē

More unnerving signals appear over the course of the following week. The Thorns have been invited to a wedding, and Mrs. Baylock is oddly strident about recommending that Damien not be brought along. Cathy insists, however, but the fit of hysterics Damien has when he gets within sight of the church suggests that the nanny knew what she was talking about. Later on, when Cathy takes Damien out for a trip to the zoo, we see that animals donít like the boy any more than he likes churches. Shier beasts like the giraffes run in terror when he approaches, but those with more aggressive dispositionsó the baboons, for instanceó take a more pro-active stance, and the apes attack Cathyís car when she and her child drive through their spacious enclosure. Cathy gradually begins to share the zoo animalsí preternatural dread of Damien, coming to believe that he is somehow alien and possibly even evil. Mrs. Baylock, meanwhile, has taken it upon herself to adopt the gigantic dog that has been haunting the grounds of the Thorn place ever since Damienís fateful party, and posting it as a nighttime guard outside the boyís bedroom. Finally, Father Brennan accosts Robert again, and warns him that his wife is in mortal peril. Brennan claims that the child Robert secretly adopted is really the Antichrist, and that Satan has placed his offspring with the Thorns because of their wealth and proximity to power. Brennan predicts that Damien will gradually engineer the deaths of every member of Robertís family, until only he remains to inherit the fortune and all that goes with it. Brennan also says that Cathy is pregnant, and that this unborn sibling will be Damienís first victim. Thorn understandably takes Brennan for a psycho, and warns the old priest never to talk to him or any member of his family again. But considering that, as soon as Robert leaves his presence, a freak accident involving a thunderstorm and the lightning rod on the roof of a cathedral leaves Brennan dead in a way that most strikingly recalls the weird development fault in the photos Jennings took of him a couple of weeks back, Iíd say Thorn ought to have taken the priestís warnings a little more seriously.

Thorn himself begins thinking in that direction soon enough. The first step on his road to total belief in his adopted sonís Satanic origin comes when Cathy tells him that she really is pregnant, just like Brennan predicted. Damien has been enough to turn her off of parenthood for good, however, and she wants to have the new pregnancy aborted. Robert, for his part, revolts at the idea. Brennan told him that Damienís sibling wouldnít live to see the world outside Cathyís womb, and Thorn seems to think that if the pregnancy comes to term, it will prove that the old priest was nothing but an obsessed lunatic after all. A couple of days later, however, Cathy miscarries as a result of a suspiciously deliberate-looking accident. The Thorn place has a foyer with a cathedral ceiling three stories high. Overlooking it on each of the upper floors is a hallway catwalk about four or five feet wide, with potted plants hanging from the ceiling. While Cathy is standing on a small table to water one of the plants on the third-floor catwalk, Damien is riding his tricycle around in frantic circles in his room. Mrs. Baylock opens the door, and Damien rides out into the hall, not looking where heís going. He crashes his trike into the table his mother is using as a stool, and she pitches over the catwalk railing to land on the foyer floor a good eighteen feet below. Robertís horrified reaction has as much to do with Brennanís prophecy as it does with the injuries his wife has sustained.

Itís at about this time that Keith Jennings looks Thorn up. Heís been looking into the mysteries surrounding Father Brennan, and he thinks Robert should know about what he has discovered so far. First, thereís the strangely suggestive similarity between the smudges on the photos Jennings took and the priestís appearance after his impalement with the lightning rod. Then thereís the diary Brennan kept, which hasnít a damned thing to do with himself, but which records the Thorn familyís movements in meticulous detail. The flat the priest rented is quite a sight, too, wallpapered (even over the windows!) with pages of the bible, and festooned with a total of 47 crosses and crucifixes. The police pathologistís report on Brennan reveals that his body was riddled with cancer, and that he had been taking morphine to kill the associated pain. It also turned up a strange mark on Brennanís bodyó three dark figure-sixes, arranged in a triangular pattern. Keithís initial guess was that this was a tattoo from a Nazi concentration camp, but the coroner told him it was a birthmark instead. Finally, Brennan kept a file of newspaper clippings relating to the date of Damien Thornís birth, many of them describing mysterious events that would surely have been interpreted as mystical portents in ages past. What makes Jennings so eager to get to the bottom of it all is a photo he took inside Brennanís flat. The priest had a mirror on one wall, and Jennings happened to catch his own reflection in the picture. Upon being developed, it showed a dark streak cutting across the mirror, right at the level of his reflectionís throat.

Thorn and Jennings will spend the next week or two chasing one clue after another, each one painting a bleaker picture than the last. Their search leads them to Rome, to a monastery in the Italian countryside, to the ancient Etruscan cemetery in which Damienís real mother was reportedly buried, and eventually to an archeological dig in Israel, where a professor named Bugenhagen (Leo McKern, from X: The Unknown and The Day the Earth Caught Fire) tells them what must be done to prevent the End Times from beginning within the present generation. It isnít a palatable prescription, believe me. Meanwhile, the forces of evil will not be standing idly by while Thorn and Jennings interfere with the plan for seizing total power in the world. And in the end, we will see that there are circumstances in which being old chums with the president really isnít such a good deal.

The Omen is one of those movies that seem to bring out unusually strong opinions in the people who see them. Praised as a modern horror classic by some, it is also denounced as nothing more than a big-studio exploitation flick by others. By far the most eccentric assessment of it Iíve yet read is that of Nikolas Schreck, author of The Satanic Screen, who castigates it essentially for making Satanists like himself look bad. Indeed, to hear Schreck tell it, The Omen is nothing more than a fundamentalist Protestant propaganda piece! Actually, Schreck is onto something there, but Iíd say heís making far too much of it, and that he has misidentified the target of whatever polemical thrust it might make. The Omenís theological perspective is as strongly Protestant as The Exorcistís is Catholic, although it takes a bit of digging to see how thatís the case. After all, the only religious figures we see in the film are Catholic priests and nuns, while the Anglican/Episcopal church to which the Thorn family belongs is seen only as a building in which Damien refuses to set foot. However, the notion that the Apocalypse is coming, and coming soon at that, is, at least in America, primarily associated with fundamentalist Protestantism. When American Catholics turn to fire and brimstone, they tend to focus more on individual damnation. Not only that, American Protestants have a long history of anti-Catholic feeling; indeed, many of the loopier sects contend that the Antichrist, when he gets here, will arise from within the Catholic hierarchy. These groups have made much over the inscription on the papal tiaraó Vicarius Filii Deió which, they point out, can be used to compute 666, the Number of the Beast, when converted into Roman numerals. (It works like this: D = 500, C = 100, L = 50, V/U [originally the same letter in Latin] = 5, and I = 1. Ignore the letters in the inscription that have no numerical value, and you get 500 + 100 + 50 + 5 + 5 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 + 1 = 666.) Notice that in The Omen, the Satanic conspiracy that places the infant Antichrist in the care of a rich and powerful family with ties to others even richer and more powerful operates out of a Catholic hospital, and that furthermore, the conspirators themselves apparently had their roles ordained for them from birth! How else to explain the fact that Brennan, who betrays the conspiracy when remorse overcomes him in the final weeks of his life, bears the same diabolical birthmark as Damien? And while Catholics are running around doing Satanís bidding, it is the holy aura of an Anglicanó that is, Protestantó church from which Damien recoils in mortal terror.

Religious politics aside, I side with The Omenís supporters. This is a very well-made movie, filled with effective performances and packing a few exceptionally powerful scare scenes. Billie Whitelawís Mrs. Baylock is one of the creepier villains in 70ís mainstream horror cinema, Gregory Peck is his usual excellent self, and Lee Remick is more than believable as Cathy Thorn. The most important performance is that of Harvey Stephens as Damien, however. Stephens, obviously, is no actor, but for this role he doesn't have to be. It is a rare five-year-old that has developed a personality distinguishable by anyone outside his or her immediate family from that of any other kid that age, so all Stephens really needs to do is sit there in front of the camera and be himself. Fortunately, screenwriter David Seltzer understood that, and gave Damien only the bare minimum of dialogue necessary to establish that he is in fact able to talk. Even so, there is one scene where the kid really shinesó itís right before the end; youíll know it when you see it.

As for those scare/shock scenes, the only movie Iíve ever seen take more brazen advantage than The Omen of the double standard for gore that lets big-budget movies get away with more than the cheap ones is Conan the Barbarian. The fate that befalls Keith Jennings is a real stunner. But this movie also knows how to get you without a gross-out. Witness the scene in which Thorn and Jennings find and open the grave of Damienís mother; I have yet to talk to anyone who didnít get at least a little jolt out of that.

Which brings me to the last point I want to raise about The Omen, a little detail that took me completely by surprise and has had me devoting far more thought to it than it probably deserves. What fascinates me the most about the grave-digging scene is that it happens in an Etruscan cemetery. Etruria was the first big-time civilization to appear on the Italian peninsula. The Etruscans were thus predecessors of the Romans, but for geographical and ethnological reasons, they canít really be considered ancestorsó rather, Rome would eventually rise up to conquer a decadent and decaying Etruria. The Etruscans are a somewhat mysterious people today. They left little behind them in the way of literature, and in any event, their written language has been only partially deciphered. Their neighbors considered them savage and brutal, and it has long been said (not without reason) that the Etruscans, at least late in their history, were obsessed with death. Certainly the archeological evidence presents that picture at first glance, for one result of the Roman conquest is that the only purely Etruscan sites that remain in any great number are their distinctive cemeteries. Whatís interesting about this in the present context is that Etruscan cemeteries are a frequently used plot device in Italian horror movies, employed in much the same way as American filmmakers use Indian burial grounds. Now The Omen obviously isnít an Italian movie, and yet its creators have pulled that very trick in a part of their movie which takes place in Italy. What gave David Seltzer the idea? Had he been watching Italian horror films himself? Or did he just do some research, and discover thereby the sinister reputation the Etruscans have in Italian popular culture? Like I said, itís a matter of less than minor importance for the movie as a whole, but itís something my mind keeps coming back to.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact