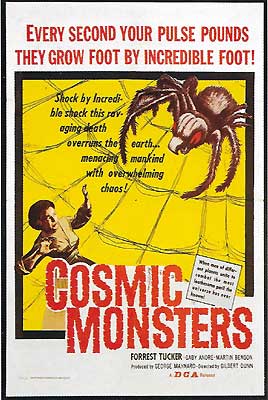

Cosmic Monsters / The Cosmic Monster / The Strange World of Planet X / The Strange World (1958) **

Cosmic Monsters / The Cosmic Monster / The Strange World of Planet X / The Strange World (1958) **

The Creeping Unknown didn’t just launch Hammer Film Productions into the horror business. Of at least equal importance, that movie also supplied the template which British sci-fi monster flicks as a whole would preferentially follow for more than a decade— although it might be more accurate to say “templates,” because different producers drew different lessons from Hammer’s success. At almost every UK firm save Anglo Amalgamated, however, copying The Creeping Unknown meant at a minimum that the British interpretation of Aliens, Rocketships, and Lunatic Science would strive to seem at least a tad more cerebral than its American counterpart. That was not always a good thing. In the case of Cosmic Monsters, based (albeit just barely) on René Ray’s novelization of her script for the 1956 TV serial, “The Strange World of Planet X,” a focus on the mere appearance of cerebrality yields a sleepy, meandering, and barely coherent film with far too many moving parts, most of which spend the bulk of the running time rusting themselves into place anyway.

Prickly physicist Dr. Laird (Alec Mango, from The 3 Worlds of Gulliver and The Playbirds) is at it again. In his laboratory converted from a manor house on the outskirts the boondocks coastal village of Briarleigh Bay, he and his assistants, Gil Graham (Forrest Tucker, of Timestalkers and The Crawling Eye) and Nicky Sayers (who doesn’t last long enough to get his name in the credits) are having another go at rearranging the molecular structures of various inanimate materials by exposing them to prodigious magnetic fields. Laird has no particular practical application in mind— his sole concern is to discover whether and how it can be done. That makes it seem like rather a high price to pay when this latest experiment goes wrong, and a power surge in the computer controlling the rest of Laird’s machinery electrocutes Sayers half to death.

The incident leads to a tense conversation between Gerard Wilson (Geoffrey Chater, of The Day the Earth Caught Fire and If…) and Brigadier Cartwright (Wyndham Goldie), the government minister and military officer whose respective departments are splitting the tab for Laird’s research. Even leaving aside what happened to Sayers, Cartwright sees only a bottomless money pit up there in Briarleigh Bay, and he’s exasperated to say the least when he learns that the scientist’s report of the nigh-fatal accident was accompanied by yet another request for supplementary funding. Wilson, however, understands just a little about the ramifications of Laird’s work, and he recommends that Cartwright pay a personal visit to the lab before he commits to pulling the army out of the project. Acting on something between a hunch and a genuine scientific hypothesis of his own, Wilson also gives Cartwright some alloy samples— a pocket-sized bar of aircraft aluminum, plus a similar hunk of another, unidentified metal which I suspect is meant to be something like HY-80 steel— for Laird and his team run through their magnetic oven. If the minister has heard correctly about what the boffins of Briarleigh Bay have achieved so far, his military partner should find the results very interesting indeed.

Cartwright isn’t the only outsider due to arrive that day at Laird’s lab. Also en route is Michele Dupont (Gaby André, from The Revenge of Hercules), whom Wilson’s agency has sent to take over from Sayers. Laird and Graham alike are aghast when the brigadier, who shows up first, warns them that their new colleague is to be a woman, but they change their tune rather quickly upon actually meeting Dupont— Graham because she’s a good-looking French gal with no current romantic entanglements, and Laird because one look under the hood of his computer is enough to tell her why the researchers keep shorting out their other equipment as soon as it starts cranking out enough power to do anything interesting. Indeed, Laird’s mis-configuration of the computer is such an elementary fuckup, so far as Dupont is concerned, that she has it ready for a full-power test that very evening.

Meanwhile, back in London, a newspaper reporter (uncredited) and his editor (Peter Copley, of Gawain and the Green Knight and The Man Without a Body) are discussing potential angles on a front-page story about a recent rash of UFO sightings. Eventually, they settle on maximum sensationalism, with an above-the-fold headline reading, “INVASION FROM PLANET X?” It isn’t at all clear what this has to do with the rest of the movie just yet, but that headline references the film’s original UK title, so it must obviously be important somehow.

Laird’s next experiment far exceeds everyone’s expectations, yielding results at once encouraging, alarming, and seemingly inexplicable. The test specimen— Cartwright’s bar of aluminum— comes out of the magnetic field chamber as brittle as rock candy, an effect dramatic enough to impress even a man sufficiently unimaginative to rise to the rank of brigadier in the British Army. At the same time, though, Dupont nearly goes the way of poor Sayers when Cartwright’s briefcase (from which he carelessly forgot to remove the other alloy sample that Wilson gave him) hurls itself across the lab toward the magnetic generator. Graham cuts the power as soon as he sees the bag straining against the hook where the brigadier hung it, but he ends up having to tackle Michele to save her from the projectile valise. And outside the lab, a baffling variety of odd things happen which Laird’s experiment shouldn’t be able to account for unless he’s underestimated his apparatus in several extraordinary ways. Radios and television sets go on the fritz all over Briarleigh Bay. A hobo (I’ve been unable to discover who this actor is, either) who’s been living in the woods around the village spontaneously receives what look like radiation burns all over his face. And an unidentified flying object crashes in the hills beyond the woods.

One set of implications is immediately obvious: Dupont’s modifications to the computer have so supercharged Laird’s machine that it can now project its magnetic field far beyond the confines of the specimen chamber. Given what happened to Cartwright’s aluminum bar, that makes the machine an inadvertent prototype for the ultimate antiaircraft weapon, and the brigadier immediately seizes control of the entire project in the name of the army. Henceforth, everything that happens at the lab is top secret, and the researchers’ highest priority will be to make the machine’s long-range effects both directional and steerable. A tall security fence of corrugated iron (the worst possible material under the circumstances, if you ask me…) goes up all around the converted manor house, military personnel start swarming into Briarleigh Bay, and Gerard Wilson arrives in person to speak for the civilian government’s continued interest in the project. Wilson also brings with him an MI5 chappy by the name of Jimmy Murray (Hugh Latimer, from Ghost Ship and School for Sex) to oversee efforts to keep the Russians from getting wind of the new direction in Laird’s work.

Graham is troubled, however. The way the machine kept running even after he cut the power suggests that there’s a feedback loop concealed somewhere in its circuitry, which could make the apparatus both a great deal less controllable and a great deal more dangerous than Cartwright, Wilson, or Murray seem to appreciate. But when he takes his concerns to Laird, the senior scientist threatens to fire him! If there’s anything more dangerous than a powerful contraption that operates on poorly understood principles, it’s an ethically-challenged genius determined not to let bed-wetters worried about safety stop him from playing with his toys.

Meanwhile, the alarming weirdness in and around the village is escalating rapidly. A stranger (Martin Benson, of Night Creatures and Tiffany Jones) sporting “obviously an agent of the International Communist Conspiracy” facial hair, and claiming the implausibly plausible name of “Smith,” wanders out of the woods one morning, takes a room at the inn, and pesters everyone he meets with questions even more suspicious than his beard. The flash-fried hobo goes berserk, and begins attacking young women, plainly intent on rape and murder (even if he’s usually chased off at the last minute by the awesome power of the British Board of Film Censors). Before Inspector Burns (Richard Warner, from Dream Demon and The Mummy’s Shroud) can do anything about him, though, Rapebum is himself killed by someone or something even worse. Eventually, “Smith” works his way around to Graham and Dupont, and the big picture starts coming into focus at last. The stranger isn’t a commie spy, but rather an operative of the alien race responsible for those flying saucers that the London papers have been howling about. His people were interested in humanity anyway, but when Laird crashed one of their spaceships by disrupting its electromagnetic drive, they realized they’d have to do something a little more hands-on than just observing us from the sky. Laird, in case this weren’t already obvious, has no idea what he’s messing with. His experiment the other night actually punched a hole in the Earth’s magnetic field, bathing the woods around Briarleigh Bay in unfiltered cosmic rays, and he can expect similar results every time he runs his apparatus at high power. It’s no skin off “Smith’s” ass, of course, but his people hate to see another sapient species destroy itself by being just smart enough to be stupid. The alien has a second set of worries on humanity’s behalf, too. The cosmic rays that Laird has already admitted could do far worse than to disfigure and madden the odd hobo. They could also induce all manner of unpredictable mutations in the creatures of the woods— and among short-lived, rapidly breeding organisms like insects, those mutations could already be making themselves felt. You didn’t think the British movie industry could make it all the way through the 1950’s without producing a single picture about giant bugs, did you?

Truth be told, though, the biggest problem with Cosmic Monsters is that it can’t quite muster the narrative discipline to be about giant bugs— or to be about anything else, either, for that matter. At first I thought this was a pernicious side-effect of the movie’s small-screen origins, that its dilatory rambling came from trying to cram at least some version of every plot curlicue from the television serial’s five half-hour episodes into just 75 minutes, but it turns out that nothing so simple or understandable is going on here. Indeed, screenwriters Paul Ryder and Josef Ambor retained barely anything from either the TV show or the novelization credited as the movie’s principal source beyond the conflict between two temperamentally opposed scientists over how to proceed when their research yields incredible, unexpected results. In Rene Ray’s telling, there were no grumbling brigadiers, no far-sighted government ministers, no dashing intelligence agents. There was no priapic hobo chasing girls through the woods. There were no flying saucers and no friendly aliens easily mistaken for dirty Red spies. And most of all, there wasn’t a single giant bug! So when Cosmic Monsters goes haring off after an endless succession of shiny objects, we can’t pin it on a counterproductive attempt at fidelity to the source material.

Ryder and Ambor surely do waste what little time they have, too. For instance, with just an hour and a quarter to fill, there’s nothing to be gained by maneuvering Michele Dupont into a love triangle with Gil Graham and Gerard Wilson, but they do it just the same. Rapebum makes sense only as a red herring to distract the Proper Authorities from the amassing menace of a forest full of ten-foot bugs, but Cosmic Monsters has no time for red herrings, and the randy bastard gets eaten before he can become one. And the UFO business in the first act is inserted so clumsily that you’ll be tempted to ask whether there was a mistake in the editing room. It comes out of nowhere, and then disappears back into nowhere until “Smith” enters the story considerably later. All the extraneous running about does create a superficial resemblance to “Quatermass and the Pit,” however, which was probably all that Ryder and Ambor were trying to accomplish, anyway.

Still, Cosmic Monsters does have its moments, if you can sit through the rest of it to get to them. Martin Benson’s droll performance during his introductory scene, in which “Smith” meets elementary school entomologist Jane Hale (Susan Redway) on one of her specimen-gathering forays into the woods, charmingly works equally well whether we suspect the outsider of working for the Galactic Brotherhood of Space Weirdoes or the KGB. Wyndham Goldie as Cartwright and Geoffrey Chater as Wilson make for an atypically sane and reasonable pair of meddling government paymasters, ably counteracting Alec Mango’s entirely too loony take on Dr. Laird. And rather to my surprise, the battle between bugs and soldiers that forms the first of the movie’s awkward tandem climaxes is really pretty good. I give it points first for the unusual array of species that it puts to work as monsters (Cockroaches! Millipedes! Tiger beetles!), but also for the care with which forced perspective, miniature-camera footage, and back projection are combined to create the illusion of their great size. It’s much better than anything you’ll find in a Bert I. Gordon movie, that’s for sure! Furthermore, there’s one bit during the battle that I can’t believe the producers got past the censors, when a giant roach ambushes one of the soldiers, and literally eats his face off. It’s strangely clean and bloodless, considering what’s supposed to be happening, but the face-gobbling is nevertheless far more explicit than the BBFC would normally have allowed during this era. Maybe it was included only in prints shipped out for overseas distribution? In any case, I wasn’t expecting it, and it isn’t often that a 1950’s big-bug movie gives you things you don’t expect.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact