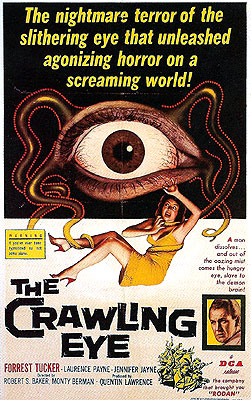

The Crawling Eye / The Creeping Eye / The Flying Eye / The Trollenberg Terror (1958) ***½

The Crawling Eye / The Creeping Eye / The Flying Eye / The Trollenberg Terror (1958) ***½

A funny thing happened in England in the mid-to-late 1950’s. Over the course of maybe seven years, the BBC produced quite a large number of very well-received mini-series in the sci-fi and horror genres, many of which were re-made as theatrical-release movies a year or two after their original appearance on TV. I’m not talking here about what happened to Tobe Hooper’s Salem’s Lot, which aired on American TV in 1979, and which was subsequently re-edited, trimmed down to about an hour and a half, and distributed to theaters. No, these BBC productions were actually re-written and re-shot for theatrical release, the film versions employing almost entirely different casts and crews from the TV versions. In America, the best-known of these movies are the Quatermass trilogy-- The Creeping Unknown / The Quatermass Xperiment, Enemy from Space / Quatermass II, and Five Million Years to Earth / Quatermass and the Pit-- but these are by no means the only examples of the phenomenon. The movie with which we now concern ourselves is another such film. The Crawling Eye, as it is generally known on the western shore of the Atlantic, was originally released in the UK as The Trollenberg Terror, the title of the TV production from which it was derived.

The story concerns the chance meeting on a train-ride of an American scientist named Alan Brooks (Forrest Tucker, from The Abominable Snowman and Cosmic Monsters) and a pair of young Englishwomen called Sarah and Anne Pilgrim (Jennifer Jayne, of Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors [not to be confused with Dr. Terror’s Gallery of Horrors], and Janet Munro, respectively [the latter is best known for her work for Walt Disney’s studio, but she was also in The Day the Earth Caught Fire]). Brooks is on his way to the remote Swiss Alpine town of Trollenberg (named for the mountain that overlooks it), while the Pilgrim sisters intend to continue on to Geneva. At least they did originally; when the conductor announces the Trollenberg stop, Anne inexplicably insists on getting off too. Call it a premonition.

This isn’t exactly out of character for Anne. The younger Pilgrim sister is a telepath, and indeed she and Sarah support themselves as a mentalist act in Great Britain. All the same, the intensity of the feeling that comes over Anne when the train pulls into Trollenberg is certainly out of the ordinary, and both sisters find it somewhat disturbing. Subsequent events will show that their unease is well-founded.

Trollenberg, you see, has been plagued by lethal accidents on the south slope of the mountain this season. A number of climbers have vanished without a trace, and the only one whose body was recovered was found messily decapitated. As you might imagine, this has not exactly done wonders for the local tourist trade, and even the villagers have started to get antsy, many of them moving into town to get away from the mountain, some going so far as to leave Trollenberg altogether. It is this that has brought Brooks to the area. Some three years ago, he and a colleague named Crevette (Warren Mitchell, who would go on to play Mr. Fishfinger in Terry Gilliam’s shamefully neglected Jabberwocky) witnessed some mysterious bad business in the Andes, and Crevette believes that the same thing is now happening in Trollenberg. Crevette now works in an observatory not far from the mountain, studying cosmic rays, and he has discovered a worrisome radioactive cloud on the Trollenberg’s south slope. This cloud would be troubling enough if it were just radioactive, but it is also perfectly static, its position never changing regardless of the strength or direction of the wind. And in case you haven’t already guessed this, all of the climbers who have disappeared did so in the region of the mountain covered by the cloud. Brooks would like very much to disbelieve Crevette; whatever happened in the Andes nearly ruined the American’s career, and he is understandably reluctant to get involved in anything similar. But before long, he will have little choice but to believe.

The irrefutable evidence comes with the disappearance of a geologist named Dewhurst (Stuart Saunders, who played an even tinier part in Horrors of the Black Museum), who goes up the mountain with Brett (Andrew Faulds, from Blood of the Vampire and Jason and the Argonauts), an experienced local mountaineer. Dewhurst hopes to find a geological explanation for the recent rash of unusual accidents, and he believes that a study of the Trollenberg’s rocks will divulge one. But his investigations are cut short when Brett wanders away from the mountain hut in which the pair chooses to spend the night, while the geologist himself is attacked by some unknown thing shortly after noticing that Brett is missing. And for some reason, whatever is up on that mountain keeps hijacking Anne’s mind, sending her visions seen through its eyes-- of Brett being lured away from the cabin, for example. The next morning, a rescue party discovers Dewhurst’s decapitated body in the hut, along with evidence that the building had been subjected to extremes of cold that were positively unearthly. And when the party later locates Brett, the mountaineer inexplicably slays all of his would-be rescuers with a pickaxe. Finally, Brett returns to the hotel where all of the principal characters are staying, and attempts to kill Anne. Brett is himself killed in the ensuing scuffle between him and Brooks, but a cursory examination of his body suggests that he had been dead for a good long time already.

At this point, it is clear that continued secrecy will do nobody any good, and a newspaper reporter named Philip Truscott (Laurence Payne, who had played the same role in the TV version of The Trollenberg Terror, one of the very few instances I know of in which an actor from one of the original mini-series I mentioned earlier returned to play the same character in the theatrical remake) pries out of Brooks and Crevette an outline of their experiences in the Andes. Apparently, the team on which the two scientists were working encountered a cloud much like that on the Trollenberg, and were faced with the same puzzling constellation of weird goings-on-- disappearances, the mental domination of a local psychic by some mysterious force within the cloud, attempts by whatever was in the cloud to kill the psychic by siccing zombie assassins on her-- that they now see in Switzerland. Brooks and Crevette never really figured out just what was afoot, but Crevette’s best guess is that a creature or creatures from another planet-- a planet whose climate and atmospheric conditions resemble those that prevail high in the mountains-- attempted to set up shop on Earth. It is Crevette’s opinion that these aliens have now returned.

The remainder of the film has the residents of Trollenberg facing an all-out attack from the aliens, who have apparently sufficiently acclimated themselves to conditions on Earth to be able to leave their roost near the mountain’s peak, and who now wish to get rid of the pesky natives. The remarkable tension that the movie has succeeded in building thus far reaches an admirable peak as the creatures corner our heroes in Crevette’s fortress-like observatory, a building specially constructed to survive in the face of even the worst avalanche. Our first look at the monsters, revealed only in the climactic moments of the film, shows them to be satisfyingly hideous, if a bit on the cheesy side. Unfortunately, a facile deus ex machina conclusion comes perilously close to blowing everything at the last possible second. But at least it is the very last possible second at which the filmmakers introduce this inexplicable lapse of taste, preventing it from living up to its full movie-wrecking potential, and The Crawling Eye remains one of the more effective 50’s monster movies in spite of its ending.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact