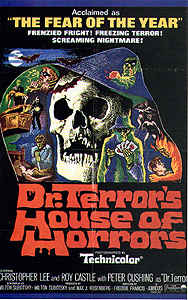

Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors (1965) ***

Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors (1965) ***

Let’s say, for the sake of argument, that you’re the head of a smallish movie studio, which you’d like to make noticeably less small in the shortest possible time. Obviously, you need money— a lot of it, and fast. What do you do? “Start making cheap horror movies” would be one obvious answer. Horror fans are famously forgiving of low budgets and all that goes with them, and most of us are shockingly undiscriminating, perfectly willing to shell out our entertainment dollars (or pounds, as we shall see once I finally get to the point) on almost anything in the genre, no matter how little promise it might hold. The strategy worked for AIP, it worked for New World, and God help us, it seems to be working for Full Moon today. But now let’s say that the horror market in your part of the world is dominated by a single, well recognized studio, which has enough of a head start on you that it is already something of an international brand name. This complicates matters, in that it forces you to decide whether you want to try competing with this studio directly, or whether you’d be better off to go in some strange other direction in which the big boy on the block might be unwilling or unable to follow you. On the one hand, the bigger studio’s success tells you that their approach sells tickets, but on the other hand, that studio almost certainly has both the resources and experience to out-compete you should your fledgling outfit and it go head to head. I bring all this up because the above scenario pretty much encapsulates the conundrum that confronted Britain’s Amicus Productions in the mid-1960’s. That horror was big, fast business was undeniable, and Amicus creative chief Milton Subotsky’s talents and interests pointed strongly in that direction anyway, but in the United Kingdom, making horror flicks meant taking on Hammer Film Productions, at least obliquely. The solution that Subotsky and his business partner, Max Rosenberg, came up with to the thorny problem of how best to do this was probably the riskiest approach of all— but also perhaps the one that offered to pay the biggest dividends if, in fact, it succeeded. Amicus would make their movies with as much of Hammer’s high-profile talent pool as they could finagle, in order to give their movies as much of the Hammer look as their lesser budgets could buy, while simultaneously adopting a couple of conspicuous quirks to differentiate Amicus product from that of its illustrious model. The quirk which would come to define the Amicus horrors to a greater extent than any other— the studio’s curious preference for anthologies— made its debut with Subotsky’s second foray into the genre, the five-piece anthology movie, Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors.

There had been horror anthologies before, of course. AIP had released its Poe anthology, Tales of Terror, back in 1962, and had given English-language distribution to the Italian Black Sabbath/I Tre Volti della Paura the following year. There had also been an overwrought effort from the heavyweights at MGM— the unfortunate Twice-Told Tales— and a few others of mostly lesser significance over the years. But Amicus made the subgenre its own, to the extent that the great majority of more recent such films bear far stronger resemblance to Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors than to any of its predecessors. The most distinctive difference between this movie and, say, Black Sabbath is that its framing sequences form a story of their own. Shortly after five strangers take their seats in a train compartment, they are joined by a sixth man (Peter Cushing), who goes to sleep almost the moment his butt hits his seat. In his slumber, he loses his grip on his leather bag, which falls to the floor of the compartment, spilling its contents all over, and awakening its owner. While the other passengers help him gather his stuff together, one of them finds a business card identifying the man as W. F. Schreck, Doctor of Metaphysics, while another discovers Dr. Schreck’s deck of tarot cards. As only one of the other men— the snobbish and arrogant art critic Franklyn Marsh (Christopher Lee)— has any idea what the deck is, this leads Schreck into an explanation of the cards’ use: the subject taps the deck three times, the reader shuffles the deck, and the first four cards drawn together tell what the future holds for the subject; the fifth card tells what— if anything— the subject can do to alter the predicted course of events. Intrigued by the idea that their fellow passenger lays claim to the power to divine their future, the other wayfarers (with the exception of Marsh, who has to be goaded into participating) talk Dr. Schreck into telling them what the cards have to say about their lives.

The first subject is John Dawson (Neil McCallum, from The Lost Continent and Moon Zero Two), an architect. As the cards tell it, Dawson is on his way to the Hebrides, where a woman named Deirdre Biddulph (Torture Garden’s Urusla Howells) has hired him to draw up plans for the renovation of her newly acquired mansion. Dawson’s family used to own the house, and he even lived in it as a child, so he seems the obvious person to direct the work. As usual, it’s a place full of ancient, unsavory secrets, which the household help— butler/groundskeeper Caleb (Peter Madden, of Fiend Without a Face and Frankenstein Created Woman) and maid Valda (Katy Wild, from The Evil of Frankenstein and They Came from Beyond Space)— seem to know a thing or two about. The cellar is locked when Dawson arrives at the house, and Valda’s professed ignorance regarding the key’s whereabouts is none too convincing. And sure enough, when Dawson manages to get a key from Caleb instead, he finds, behind a recently installed wall of hollow plaster, an antique coffin, which Caleb identifies as that of the legendary Cosmo Valdemar. Valdemar had once claimed the Dawson mansion as his own, and was said to have been buried secretly on its grounds even after the Dawson family wrested control of it away from him, something like three centuries before. And following the standard operating procedure for aggrieved property owners in gothic horror films, Valdemar is also said to have vowed to return from the dead to reclaim his house someday. Of course, none of this really explains what a centuries-old coffin is doing concealed behind a wall that dates from, at most, a couple of years ago.

It’s a safe bet the coffin is the actual article, though, because no sooner has Dawson discovered it than a wolf starts prowling noisily about the chateau grounds— do I really need to tell you there aren’t supposed to be any wolves in the neighborhood?— and making a major pest of itself. How big a pest, you ask? Well, it kills Valda, for starters, and given that Cosmo Valdemar’s coffin turns out to be empty when Dawson and Caleb open it up, I rather think it’s going to take a bit more than your standard .303 hunting rifle to kill the thing. And for that matter, the fact that somebody moved the coffin to its present location only very recently suggests that someone in the house probably doesn’t want the werewolf killed at all...

Next up is Bill Rogers (Alan Freeman). The cards see him returning from a vacation with his wife, Ann (Ann Bell, from Student Bodies and The Devil’s Own), and daughter, Carrole (Sarah Nichols), to find something very strange in their garden. Growing up the side of their house is a stout, leafy vine, which not only moves of its own accord, but actively resists being cut. Bill gets a piece of it anyway, which he takes to the nearest university, where professors Drake (Jeremy Kemp, from the 1983 TV version of The Phantom of the Opera) and Hopkins (The Brain’s Bernard Lee, probably best known for his portrayal of M in the James Bond series) are sufficiently enticed by the prospect of describing a hitherto unknown species of plant to overcome their understandable skepticism in the face of stories about an automotive vine with a survival instinct. Drake comes round to the Rogers house to have a look, and he just narrowly misses witnessing the vine in action when it kills the family dog. Not to worry, though, as he gets another chance to see it the next day— of course, his enthusiasm is doubtless hampered a bit by the fact that this opportunity comes while the vine is killing him, but beggars can’t be choosers, as they say. And now that we’ve established the vine’s lethality to humans as well as dogs, the question arises of just what Dr. Hopkins proposes to do next. After all, vines grow very fast, and they’re famously difficult to kill...

The third man to submit himself to Dr. Schreck’s mystical investigations is Biff Baley (Roy Castle, from Legend of the Werewolf and Dr. Who and the Daleks), leader of a popular London jazz band. Schreck predicts a visit from his agent, Sammy Coin (Kenny Lynch), presenting an offer of a splendidly exotic booking. If they want it, Coin can get Baley and his band a series of gigs in Haiti. Hey, why not?

Well, there is that whole voodoo thing. Most real-world travelers never have to worry much about that, but nobody in a horror flick has ever gone to Haiti without ending up on at least one witch doctor’s bad side. The leader of the Calypso band with which Baley’s boys will be playing (Christopher Carlos) warns Baley to take the local religious customs very seriously, and to give them a wide berth, but naturally, Biff doesn’t listen. Instead, he steals away late that night to eavesdrop on a voodoo ceremony out in the woods, and is so impressed with the music that he jots an approximation of it down for future use in one of his own songs. Yeah, well maybe Biff ought to work out a royalties agreement with Dambala the Voodoo God before he performs that song onstage...

And now it’s that asshole Marsh’s turn. The cards reveal that Marsh, who uses his position as art critic for some important newspaper or other as a forum for railing against Abstract Expressionism, Action Painting, and the like, has a particular favorite whipping boy in the form of painter Eric Landor (Michael Gough, from The Crimson Cult and Crucible of Horror). Marsh never lets slip an opportunity to rag on the poor son of a bitch, but one day, Landor gets back at his tormentor in a most ingenious manner. After enduring another tongue-lashing from Marsh at the gallery where his latest works are on display, Landor arranges for the critic to be presented with a painting by an “exciting young artist” as yet unknown to the critical community. Marsh loves the painting, which he pointedly compares to Landor’s work, and he is ecstatic when he learns that its creator is in the gallery at that very minute. But unbeknownst to Marsh, the whole thing is a setup; the canvas was painted by a trained chimpanzee, and when one of Landor’s friends brings the chimp out to meet Marsh, the critic is humiliated. Landor rubs it in, too, over the course of the next several days, following Marsh around town and doing things like “absentmindedly” cutting out strings of paper dolls in the shape of apes while sitting where Marsh can see him out of the corner of his eye. Eventually, Marsh snaps, and runs Landor down with his car, crushing the painter’s right hand to a useless pulp.

This, of course, means Landor’s career is over, and the former artist becomes so despondent at the prospect that he shoots himself. Marsh reads about the suicide in the paper the next day, and is hit with a wave of gnawing, obsessive guilt, but he’s not going to get off that easy, no not at all. Once Landor is in his grave, Marsh starts being haunted by the painter’s disembodied right hand, which follows him everywhere he goes, and resists even the most conscientious efforts to destroy it. Now most of your crawling hands are stranglers, and at first, it looks like this one is too, but by the end of the story, we’ll see that it has something altogether more appropriate in mind for Marsh...

There’s only one man left in the compartment now whose future remains untold, and at last, Dr. Bob Carroll (Donald Sutherland, from The Puppet Masters and the 1978 version of Invasion of the Body Snatchers) submits to Dr. Schreck’s uncanny vision. The prediction begins with Carroll’s marriage to a Frenchwoman named Nicolle (Jennifer Jayne, of The Crawling Eye and The Medusa Touch), who is moving into the doctor’s house in a small English town. It won’t take you long to figure out that there’s something fishy about Nicolle. It isn’t just that she seems to take an instant and irrational dislike to Carroll’s colleague, Dr. Blake (Max Adrian, from The Devils and The Terrornauts), or that she appears eager to get her husband out of the house as soon as possible in the mornings, although those things certainly enter into it. No, far more suspicious is what Nicolle does at night. While Bob sleeps, Nicolle sneaks out of bed and leaves the house to go God alone knows where. And surely it can’t be a coincidence that Nicolle’s arrival in town comes at the same time as a curious outbreak of pernicious anemia, can it? Well, as generally happens under these circumstances, Dr. Blake, who examines all the “anemia” patients when they come in, notices a pair of little round wounds on the neck of each sufferer, and (because we only have about fifteen minutes to work with here, rather than the usual 90) he comes with unseemly speed to believe that his town has been invaded by a vampire. A little detective work singles out Nicolle as the most likely suspect, and Blake is able to convince Carroll at least to hear him out. Whittling the other doctor a stake, Blake tells Carroll to feign sleep one night, and then see if Nicolle goes anywhere in the wee hours of the morning. If so, he should wait up for her, and look closely to see if she has blood on her lips when she returns— then he’ll know for sure whether his colleague’s suspicions have any validity. The only problem with this plan is that Nicolle isn’t the only person in town with a dirty little secret...

Finally, we return to the train compartment for one last look at our heroes, at which point we may be surprised to learn that their story has an actual ending, too. And that ending, while it may not make much sense when you really think about it in the context of the film, definitely does exhibit a certain thematic harmony with what we have seen thus far...

It makes a good bit of sense that Milton Subotsky, who got his start as a maker of educational shorts, would make his mark on horror movie history with an anthology film. Brevity and directness were the name of the game in the field where he learned the ropes of filmmaking, and that training serves him well in writing Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors. The five tales (six, if you count the framing story) are short even by the standards of previous anthologies— none runs longer than twenty minutes, and most are down around fifteen— and Subotsky’s familiarity and skill with the short form is reflected in the remarkably uniform quality of all of them. Some are better than others (I’d put Franklyn Marsh’s story first [the crappy mechanized rubber hand notwithstanding], and the one about the killer vine last), but there is neither a standout winner nor a standout dud, a situation almost completely unheard of in this subgenre. And as for the outcome of the studio’s risky venture of trying to strike the balance between direct and oblique competition with Hammer Film Productions, the gamble paid off handsomely in both the artistic and financial senses. Lee and Cushing add a degree of weight to the film that it would not have had with Gough and Sutherland alone, while another familiar Hammer name, director Freddie Francis, contributes a level of class and craftsmanship that is all out of proportion to the movie’s visibly tiny budget. Even with shitty film stock, cheap cameras, and cut-rate lab processing, Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors looks awfully good. And of greater importance in the long run, Amicus was able to capture the public’s attention, and would become by the end of the decade the second-biggest studio in Britain specializing in horror films. Sometimes fortune favors the talented, too.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact