Dr. Who and the Daleks (1965) -*½

Dr. Who and the Daleks (1965) -*½

It kind of feels like I’m admitting to something shameful by saying this, but I’ve never been able to get into “Doctor Who.” I tried— I really did. It was on PBS all the goddamned time when I was a kid, and with that menagerie of crappy rubber monsters, you can bet it caught my eye on any number of occasions. But I never managed to catch the first episode of a story arc, so I never had any idea what was supposed to be happening, and the very premise of the show was utterly opaque to newcomers by the mid-to-late 70’s, when the episodes that introduced me to the series were produced. The guy with the huge hair and the scarf never seemed to do anything, and those people he palled around with were absolutely unbearable. (Don’t even get me started about that stupid robot dog, either!) A lot of the episodes I watched appeared to be almost literally plotless, managing the impressive feat of being even more boring than “The Tomorrow People.” And finally, there was just something esthetically displeasing about the whole show, which I couldn’t put my finger on at the time; in retrospect, I think I was reacting to the low-tech videotape the BBC used in the 70’s, which could make virtually anything look half-assed and junky. I know I should give “Doctor Who” another chance now that I’m an adult, but the relaunched series that began in 2005 sounds completely unappealing, and the thought of delving into the original— which ran for 26 years, but now has huge gaps toward the beginning thanks to the BBC’s penurious attitude toward archiving during the 60’s and 70’s— just makes me tired.

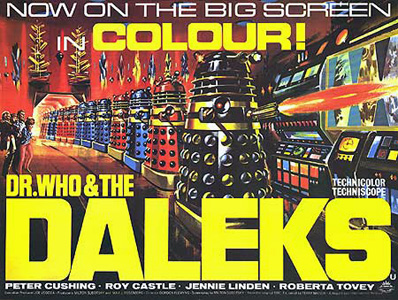

That still leaves one possible avenue, though. In 1965, when “Doctor Who” was enjoying its first peak of popularity, Amicus Productions teamed up with a company called Aaru to make the first of two big-screen adaptations, with Peter Cushing replacing William Hartnell in the title role. I realize that neither film is terribly representative of the television version. Most notably, the series hadn’t yet established that the Doctor was a nigh-immortal alien, so Dr. Who and the Daleks treats him as just a dotty B-movie scientist on the Cecil Kellaway model, and the characterization of his early companions has been revised almost beyond recognition. Still, it seemed like watching the movies might be a relatively stress-free way of testing whether “Doctor Who” had something to offer me after all. And in a weird sense, the experiment has left me with some desire to take another look at the TV show, if only to the extent of checking out the seven-episode serial from which Dr. Who and the Daleks derives. Everything I’ve read indicates that The Daleks was what put “Doctor Who” on the map, culturally speaking, and it scarcely seems possible that it could have done so if it were as comprehensively awful as the feature film.

Dr. Who (Peter Cushing) is spending a quiet evening at home with his granddaughters, the twenty-ish Barbara (Jennie Linden, of Nightmare and Old Dracula) and the ten-ish Susan (Roberta Tovey, who later played small parts in The Beast in the Cellar and The Blood on Satan’s Claw), when the elder girl’s bumbling, cowardly lummox of a boyfriend (Roy Castle, from Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors and Legend of the Werewolf) shows up. The old scientist is not nearly as miffed at Ian’s intrusion as you might expect, though. Partly that’s because Who is apparently too senile to stay miffed at anything very long, but it’s also because the boy’s arrival gives him an audience before whom to show off his latest invention. He calls it Time And Relative Dimension In Space— TARDIS for short— and it’s probably the most revolutionary transportation technology anyone ever thought of. A sort of combined spaceship-time machine, TARDIS permits more or less instantaneous travel to any place in the universe at any moment of the past, present, or future. It’s also considerably bigger on the inside than it is on the outside, and for reasons only the gods (or those who’ve seen the first episode of the TV show) can fathom, its exterior is disguised as a police telephone box. Ian is so impressed with the contraption that he temporarily loses control of his higher motor functions, and stumbles into the lever that activates it.

Dr. Who didn’t have the TARDIS programmed for any particular destination, so he has no idea where or when they are at the end of the trip. All anyone can say is that the planet looks like it’s been dead a long time. The dense forest where they land, so to speak, is petrified, as is the only animal the travelers can find, and the soil is nothing but sand and ashes. Also, there’s something strangely enervating about the atmosphere, something that makes everyone aboard the TARDIS feel sort of tired and lightheaded. Mind you, that’s not to say that the place is without interest. From the edge of the forest, across a narrow but unforgivingly rugged plain, a huge city can be seen. It looks just as dead as the woods, but the nature of cities is that it’s possible to stay indoors in them. There may be activity that isn’t visible from where Who and his companions are standing. Still, Barbara, Susan, and Ian are unanimous in wanting to return to 20th-century Earth, so the doctor grudgingly goes back with them to the TARDIS. On the way through the woods, Susan is sure she feels a hand touch her shoulder, but that mystery will have to remain unsolved. Or not… Actually, it turns out that Who and the gang will be sticking around a while longer, because the machine isn’t working. The fluid link has sprung a leak, and although Who can reseal it easily enough, replacing the spilled mercury is another matter. The doctor keeps stuff like that in his laboratory, which is back on Earth in 1965. The only plausible source of mercury around here is the city across the plain, so it looks like the travelers will be investigating it after all.

Naturally, the city isn’t really abandoned, but we’ll get to that in a bit. First, there’s a sign of life closer to hand, in the form of a little metal box containing several ampules of clear, pink liquid, which somebody left outside the door to the TARDIS during the night. Who and company could save themselves a lot of trouble later on by bringing the box with them, but they don’t know that yet, and they all want their hands free for the treacherous trek to the alien metropolis. They lack even that good an excuse, though, for their first action upon entering the still-functioning main gate. Like the idiots that all of them save Susan are, the gang split up to explore the city, making it all the easier for its inhabitants to capture and confine them. Those inhabitants are the Daleks, one of two intelligent races on this world, and arguably the victors in the neutronic war that destroyed its ecosystem untold centuries ago. Ever since that conflict, the Daleks have been forced by the residual radiation to live confined not only to the underground portions of their city, but also to lead-lined mechanical bodies resembling the galaxy’s most sinister garbage cans. Their temperament is not unlike that of Oscar the Grouch, either. As for their opponents in the war, they were called the Thals, and a few of them survived its ravages, too. The Thals normally live as far from the Daleks as they can manage, but a recent crop failure has driven them into the petrified forest in the hope of finding something still alive and edible. At least they don’t have to worry about the radiation, because they’ve perfected a drug to safeguard them against its effects. Yes, that would be the pink stuff in those vials Dr. Who and his companions found earlier. And yes again, that does mean that the Earthlings’ strange malaise marks the onset of radiation sickness, which will kill them in a matter of hours if something isn’t done about it. What did I say before about that box saving them trouble if they’d brought it along? There’s a harder bite in the ass even than that, too. Now that they’re all on the verge of paying with their lives for his foolishness, Who confesses that there was never anything wrong with the fluid link (which, by the way, the Daleks confiscated for study when they locked up the humans). He made the whole thing up just to create an excuse to see the Dalek city up close. Jackass…

The Daleks have been listening in on their captives’ conversation in the holding cell, and the news of a package of drugs dropped off by the Thals sparks considerable interest. If they could just get their hands— or whatever those things are— on a reasonably large amount of the chemical, they could use it to synthesize a supply of their own. Then they could leave the city in force, and exterminate the last of their old enemies. With that in mind, the Daleks make a bargain with the humans. They’ll release one of the prisoners to retrieve the drugs on the condition that he or she hand over the remainder after sufficient doses have been administered to cure Earth-people’s illness. Or at any rate, that’s the version they tell Who and company. Being the bad guys around here, the Daleks actually plan to stiff their captives, keeping the whole stock of the Thal drug for themselves. Inevitably, Susan is the only one both brave enough and well enough for the mission.

Susan is thus the first human to make contact with the Thals, beginning an alliance that will serve the travelers well as their situation evolves. Knowing the Daleks as he does, the Thal leader, Alydon (Barrie Ingham, from Invasion and The Fourth Square), gives Susan a second box of the drugs as insurance against treachery, and extends his people’s welcome to the humans should they manage to escape. They do, thanks largely to the Daleks being even dimmer and less competent than Ian, but their troubles are still far from over. There was no time during the breakout to recover the fluid link, so now the travelers really are stuck unless they return to the city and get the part back. That would require some serious outside help, but Alydon refuses to have anything to do with such an undertaking, on that grounds that stealing the fluid link back from the Daleks would necessarily entail fighting them. The experience of neutronic war has turned the Thals into doctrinaire pacifists— a noble stance to be sure, yet one that seems rather self-defeating for people who have to live on the same planet as the Daleks. Just how self-defeating is revealed (to us, anyway) when the Daleks test the Thal anti-radiation drug, and discover that it gives them mad cow disease. With their last hope of ever leaving their city or their armored trash cans dashed, the spiteful creatures pull their last few neutron bombs out of storage for a truly apocalyptic temper tantrum. Dr. Who has no idea how urgent the issue really is as he tries to convince the Thals that some things truly are worth fighting over.

I know a fair number of “Doctor Who” fans, and they’re practically all in agreement that the appeal of the series lies in the characterization of the Doctor as someone who thinks his way out of a fix (even if the writers have an unfortunate tendency to equate that with finding ever more exotic applications for something called a “sonic screwdriver”). I therefore think I’ve pinpointed the number-one reason why fans of the television show seem to have little but disdain for Dr. Who and the Daleks: the aforementioned debate with Alydon— and more to the point, the sneaky trick Who employs to win it— is the only instance in the whole film of Dr. Who living up to their image of the Doctor. (Incidentally, despite all the stink fans like to raise about non-fans— including the ones who made this movie and its sequel— failing to grasp that “Doctor Who” is not actually the character’s name, I can’t help noticing that the same point was often equally lost on the people who designed the title scrolls for the show’s closing credits.) For the rest of the running time, he’s a doddering old fool who does nothing at all to get himself or his companions out of trouble, and a fair number of things to get them all deeper into it. Even for someone like me, who isn’t a fan of the series, that’s incredibly frustrating. From what little I’ve seen of and read about the William Hartnell years, that initial incarnation of the Doctor was often a prickly, inconsiderate jerk, but at least he could be counted upon to maintain a plausibly consistent level of intelligence and perspicacity from one moment to the next. The genius who can’t be trusted to tie his own shoes is one of my very least favorite character tropes, and the Amicus-Aaru Dr. Who is the reductio ad absurdum of the type.

The diminution of the Doctor is part of a larger phenomenon, though, which goes some way toward explaining it. It’s easy to lose track of this today, but “Doctor Who” was originally intended as quasi-educational programming for children. It was designed to sneak lessons about science and history past the defenses of kids who just wanted to watch the adventures of a time-traveling genius and his teenaged daughter. The Daleks was actually a major departure from the stated mission— indeed, Terry Nation’s script for the serial was initially rejected as exactly the sort of fantastical junk entertainment to which “Doctor Who” was supposed to provide an antidote, and only the inexorable pressure of a weekly broadcast schedule saved it from the trash can. Meanwhile, both Amicus and Aaru were headed by American expatriates who always had one eye focused on the prospect of transatlantic distribution. The US audience for sci-fi movies was generally assumed to be very young in the mid-1960’s, so it would make sense for a film adaptation to go back to the show’s roots in a sense, by expressly targeting the juvenile market. Furthermore, “Doctor Who” didn’t make it to American television until 1972. The biggest potential audience for Dr. Who and the Daleks would therefore come into it with preconceptions engendered not by the TV series, but by the likes of Tobor the Great, The Invisible Boy, and Santa Claus Conquers the Martians. Thus this version of the story has been kiddied up, not just by making Dr. Who a silly old duffer, but in just about every way imaginable. The Daleks now come in a vivid array of designer colors, and their ray guns have been replaced by nozzles spraying carbon dioxide foam. Susan is no longer a teenager, but a child of about the same age as the desired viewer. Barbara is now a bitchy big sister, and Ian has been reduced to an agent of slapstick comedy. Most of all, Susan has absorbed into herself virtually all the intelligence, competence, and courage of the entire cast, embodying common childhood fantasies of independence and heroism. She’s actually a pretty interesting character as a consequence, and if producer Milton Subotsky had called this movie Susan and the Daleks instead, it might have fewer enemies today. Enemies were not a problem in 1965, however; Dr. Who and the Daleks was one of Amicus’s all-time biggest hits.

Still, I’m siding with the naysayers. The most serious self-inflicted injury here is the trimming and sanding of all the pointy bits for fear that Dr. Who and the Daleks would otherwise be too intense for children. From what I saw of them in my long-ago TV dabbling, the original-recipe Daleks were damned impressive villains for a bunch of squids who live in rolling trash hoppers. These Daleks, though, are about as scary as Marvin the Martian, not least because they’re as easy to outwit as they are to outrun, outclimb, and outfight. That’s the whole point, I realize, but the softening is predicated upon a fundamentally faulty assumption— that kids can’t handle being scared— and it hurts the movie by deflating all its efforts to create tension. Can our heroes survive the Daleks’ fiendish plan to keep the Thal anti-radiation drug for themselves? Of course— these bucket-dwelling nitwits would never think to search Susan for a second medkit. Can they escape from their prison cell and evade the guards long enough to reach the city exit? Obviously— if the Dalek guards can’t even be bothered to notice that the captives have destroyed the television camera whereby their jailers keep tabs on them, tricking them into any of the innumerable situations where they’ll be rendered helpless by the limitations of their environment suits will be no trouble. Can Who and his companions retrieve the fluid link and get the TARDIS working again for the trip home? The only thing that could stop them is an epidemic of self-destructive stupidity on the Thals’ part. We all know up front that the good guys are going to win in a movie like this one, but the baddies should at least be able to make them work for it. That’s true no matter how young an audience you’re aiming for.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact